Bite me

“What’s he mean, calling me a dentist? I wouldn’t hurt anybody, let alone a tooth.” —William Saroyan, The Time of Your Life, 1939.

1.

When cavities, thus, the solid tooth destroys, That sullen enemy to mortal joys, The tooth-ache, supervenes: — detested name, Most justly damned to everlasting fame!

—Solyman Brown, “Dentologia; a Poem on the Diseases of the Teeth And Their Proper Remedies,” 1840.

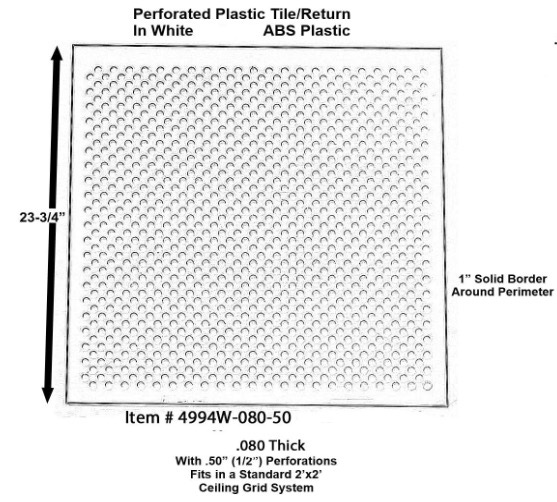

There is for me no view so stultifying as the water-stained ceiling tile above my dentist's chair. Nor any so enduring: what else in this wide maculate realm has so entirely possessed my eye? I have spent more continuous and discrete time staring at it than at any other object in the universe: no painting or poem has so entranced me, no star-filled night nor all the skies of night and day combined have so entirely fixated and devoured my gaze.

Yet with this implacable transfixion comes release, and a form of redemption: in the fixed presence of this two-foot square of fibreboard I throw off the yoke of the world, it becomes the face of God and I its anchorite, the green chair my high column, the anaesthetizing needle’s prick the mortification of my flesh, the drill my self-crucifixion, the dentist the means of deliverance and my exhorted, my awestruck, my cenobitic following.

The soul, though, is not strengthened by these withdrawals into mineral slag. With the last spiralling spit and the unclipping of the bib, I do not leap to the ground refreshed, readied to do yeoman’s work in the struggle with devil and flesh. For I am not emotionally disposed to optimism. Why fix teeth when the world itself is rotten to the core? Optimism depends upon internal organic conditions—self-confidence, a cheery and ceaselessly extensible view of the semi-permanent, an inner belief in continued being and future success—not pearly whites.

I sleep in my clothes. Why take them off only to have to put them on again later? I can barely muster the long-term view that a haircut requires or the purchase of a pair of socks. We are lost and on the brink of collapse. What point could new socks have now?

By comparison, a visit to the doctor solicits a confusion of contemplative riches. Laid out on the paper towel roll of an examining table, cold basted with ultrasound jelly and rotated like a chicken in a roasting pan, one’s attention, assailed by a host of the real and the projected, is kaleidoscopically divided, as compound and richly facetted as a fly’s eye, as easily and repeatedly split as an electrically stimulated oocyte in a Petri dish.

For each prescription ("turn on to your right side, please…”) a new perspective. For each perspective a new state of being. For each new state of being a new obligation for observation and reflection—most of it dull and dark, yes, but a compelling hierarchy of contemplative foci just the same: near the top of the wall, scratches and scrapes in the dun-coloured paint; plastic screw anchors even higher; and then, at the vertex, the ghosts of the flat and framed objects once supported by the shelves supported by the screws supported by the plugs. What landscape, whose picture, what diploma once filled that now phantom frame? Where is the machine once battened to that wall and what medical advancement caused it to disappear? Will its replacement save my life? Am I to be saved? Am I worth saving? Each element solicits a verifiable re-connection with the world—a thickening of being and its scattering to the winds.

At the dentist's, however, I only look up. Up, up, up. Today, again, an entire morning spent staring at the tile above the chair, first at the contours of the stain, imagining the water puddling in darkness on its upper surface, wondering when it will reach critical volume and cause the tile’s fall and the ceiling’s collapse, which elicits this bitter thought: that my life too is a hidden pooling, a brackish blackness ready to cave in.

Next, the irregular patterns of holes in each ceiling square, which I do not count but absorb: I take in their number and assimilate their warp and woof even though I know there are none to be found. I take the holes in at a glance, fix them with a stare, then, squeezing shut and opening wide, make them flicker and strobe, transform them into spidering lines of ghostly light, a plotching universe of dancing constellations, replicating, bleeding, polar swapping from black to white to red, red to black to white, red, black, white, red, red, red. As the throb in the eyes intensifies the throb in the jaw recedes and with it, the sound of the drill, deadened as if by a sheet of gypsum. This is a trick: bat away questions of origin, existence and composition, empty the brain of the whys and whats and focus the entire force of being on the air circulating through an irregular pattern of perforated holes in a two-by-two-foot square of recycled cellulose. Then choose one hole and slip through, into the dead space concealed behind it, a hidden universe of fixtures, pipes and wires, fermenting condensation, black mould, butyric acid, rats’ nests and asbestos fibres. Then ask the real questions: Is this my life? Is this my world? Is this, then, what I have become? An irregular pattern of perforations, a surface where consciousness collects and stagnates? A tesseral grid suspended from the original—a mask, a buffer? Not buffer in the sense of dull yellow or naked or in good physical shape. Not an aficionado or pundit, not a freak or a fanatic. Buffer: from the old, lost verb to buff; the sound of a blow to a soft body. Like the recoil mechanism on a gun. A duffer as much as a buffer.

Time to take off this wretched bib around my neck, drop the tray and get on with my life.

2.

Napoleon, we are told, was born with a beautiful, strong, and well-arranged set of baby teeth. His permanent teeth were said to be even more astonishing. As emperor, in the evening, after his ablutions, he would carefully pick at them with a toothpick made of boxwood, clean them for a long time with a brush soaked in a special opiate, floss with thin coral, and rinse his mouth with a mixture of brandy and fresh water. Finally, he would clean his tongue with a scraper of silver gilt or tortoiseshell.

For he was a man fixated and set in his ways. Goethe described him as a “man of granite”: “What could he not and did not venture? From the burning sands of the Syrian deserts to the snowy plains of Moscow, what an incalculable number of marches, battles, and nightly bivouacs did he go through? And what fatigues and bodily privations was he forced to endure? Little sleep, little nourishment, and yet always in the highest mental activity. When one considers what he accomplished and endured, one might imagine that when he was in his fortieth year, not a sound particle was left in him; but even at that age he still occupied the position of a perfect hero.”

And yet, on St Helena’s, in his forty-seventh year, the exiled emperor had, for the first time in his life, a toothache.

“I found him with his face wrapped up with a handkerchief,” his dentist, Barry O’Meara, wrote in one of the clandestine letters.

“‘What is the most terrible ache? What is the sharpest pain?’” he asked me.

I answered that it was always the most instantaneous one that was the worst.

“‘Well, then it must be this toothache!’”

3.

Our specialized molars, canines and incisors are without parallel in the animal kingdom. Human tooth enamel is as strong as iron, with a value of five on Moh’s scale of mineral hardness. The force of our bite is more powerful than the Earth’s gravitational pull.

A bird just hit the window. Of no consequence in the bigger scheme but still the most traumatizing event I have physically witnessed since the death of my dog a year and a half ago—so alarming I feel compelled to record it here.

Why? The histories of my parents and theirs, both lines, both sides, were undocumented, and because of that forever gone, while the bird's lifeless form, lying broken under the window, shall live a while longer under your eyes in these words. The hard, bony, enamel-covered structures in my mouth, however, are not long for this world. The enamel, once harder than iron, the bite once rivalling the force that binds all things and beings to the Earth’s crust, have been compromised by carelessness, by hygienic neglect. I chew carelessly. I brush lackadaisically and I do not use a brush, I use a gum tree branch, or, when available, a Neep-Neep twig, which, besides being delicious, freshens breath.

I do not floss.

And now they ache. I bite down on an almond, a cough drop, a sweet pickle or a slice of banana and the stab of pain brings tears to my eyes. Is the enamel gone? Are my tissues rotted through? My dreams are sinister. My thoughts are slung under a low seething cloud. Crushing torment propels me forward. New wreckage is hurled at my feet every morning. The debris piles up, towering skyward.

“Don’t make a fuss,” was what my mother used to say. I found a box of hers yesterday, mainly letters and a stack of photographs, all with her head scratched out. Or her whole body cut out with scissors. Why would my mother redact herself from family snapshots? She jumped out of the frame at the first sign of a camera, turned her head away, or leered at the lens like a mad woman, as if saying, here I really am, even more absurd than you thought. She hid behind a mask of contempt — of self-contempt.

Don’t we all? Hiding what? Sanitizing. And yet she kept the photos, she didn’t throw them away, she glued every one of them into photo books with little black triangles at the corner.

4.

My teeth? They’ll do. In fact, for the record, I am grateful; I relish the prospect of pain so close to my brain. It will keep me focused. Besides, what’s a little dental work compared to the everyday misery of the common man? Montaigne:

Everyone knows the story of Scaevola, that having slipped into the enemy's camp to kill their general, and having missed his blow, to repair his fault, by a more strange invention and to deliver his country, he boldly confessed to Porsenna, who was the king he had a purpose to kill, not only his design, but moreover added that there were then in the camp a great number of Romans, his accomplices in the enterprise, as good men as he; and to show what a one he himself was, having caused a pan of burning coals to be brought, he saw and endured his arm to broil and roast, till the king himself, conceiving horror at the sight, commanded the pan to be taken away.

Teeth are tiny. The world is vast and mad. And yet it has its logic. Montaigne:

The last death will be so much less painful; it only kills half or a quarter of a man. Recently, a tooth of mine fell out, without pain, without effort: it was the natural end of its duration. That part of my being and several others are already dead, others half-dead that were the most active and held the first rank while I was in the prime of life. This is how I melt away and escape from myself. What stupidity it would be for my understanding to feel the height of this fall, already so advanced, as if it were whole! I hope I shall not.

Montaigne tells us that he too often chewed and brushed carelessly. He confessed to tongue, cheek and finger biting. He also wrote about seeing a man who, with his teeth, and without the help of any hand, could bridle, groom, rub, dress, saddle, girt, and harness his horse. And when they opened his tomb four years ago they found his skeleton intact, with almost all his teeth accounted for.

5.

An old joke: What do you call the fleshy part around teeth? Me.

Besides, how difficult can it be to pull a tooth? That said, I couldn’t do it, I can’t stand the sight of blood and the sound is revolting, a horrible crunching and cracking right next to the brain, worse because of the anaesthetic. Because you feel nothing. Not a thing. Saint Appolonia did not need anaesthetics, why should I?

Perhaps it is time for an intercession. Saint Apollonia, the deaconess of Alexandria during the reign of Emperor Philip, is the patroness saint of dentists. She carries pincers holding a tooth or wears a golden tooth on a necklace. When the persecutions began, she alone refused to flee the city, and the pagan mob set upon her and beat her till the teeth fell from her mouth. Then they lit a fire. “Curse your God,” they cried, “or we will turn your flesh to ash.” “Wait,” mumbled Apollonia. “Give me time to consider.” Then she jumped into the flames.

6.

Toothaches drove us from the trees. Not hunger, not fear, not ego, not free will, not sex, not God. Debilitating pain in the oral cavity and the quest for its relief is the driving force of all civilization.

A corollarial extension: local anaesthesia—the blocking of the perception of pain and the reversible loss of sensation through the prevention of nerve impulse transmission in a specifically targeted zone of the body—divides us from the ancients. It, not dentistry—we’ve been drilling teeth for 9,000 years—is the single innovation that delineates our modernity.

The ancients used snow and ice or wine and opiates. We use dibucaine, prilocaine, lidocaine and mepivacaine. The best are amides, derivatives of aniline. Amides are heat stable and have a two-year shelf-life. Ester local anaesthetics, like cocaine—Freud’s favourite, first used at his suggestion by Karl Koller to numb gums in 1884—are faster acting but unstable in solution and more likely to elicit allergic reactions.

Decades later a dentist told a patient of Freud’s ("The Wolf Man," Sergei Pankejeff (1887-1979)) that he “would soon lose all his teeth because of the violence of his bite” and that his gums were pocked with pustules, gum-boils and “little holes.” Years after his “cure” he was seen walking the streets of Vienna staring at his reflection in a mirror. “Professor X has drilled a hole in my nose,” he would tell alarmed passers-by. The teeth trouble continued, as did his distrust of the dental profession. According to Freud, his earlier attitude toward tailors “precisely duplicated this later dissatisfaction with dentists … he went about from tailor to tailor, bribing, begging, raging, making scenes, always finding something wrong, and always staying for a time with the tailor who displeased him.”

7.

Abraham Lincoln shared the Wolf-Man's distrust of dentistry after losing part of his upper jaw during a botched extraction during his first dental intervention, which was performed by a chiropodist without anaesthesia. The bone broke off in the grip of the man’s pliers. Dentists, understandably, second only to photographers and portraitists, alarmed Lincoln thereafter. He never smiled, no matter how good the joke or amusing the situation—and during subsequent dental visits (of which there were only three) self-administered chloroform, sniffed from a small cork-stoppered flask he carried with him at all times in the hind pocket of his waistcoat.

Of George Washington’s cherry wood dentures and John Quincy Adams animal teeth, etc., we are depressingly familiar.

Andrew Johnson—the first man to assume the highest office in America because of an assassination, and the first to be successfully impeached—avoided public appearances whenever possible because of a “tendency to purse his lips and drool.”

An abscessed tooth, not the saloonkeeper’s bullet mentioned two weeks ago, killed Teddy Roosevelt.

The deplorable state of Woodrow Wilson’s teeth was responsible for his debilitating stroke of 1919.

8.

Throughout the war Winston Churchill wore a set of loose-fitting upper dentures that did not connect directly to his palate but hung slack in his mouth, creating a mouthful-of-pebbles effect.

This was intentional. Not, as Demosthenes did, to correct a speech impediment, but for the opposite effect—to preserve Churchill's “signature” drunken lisp for radio broadcasts.

Churchill asked his dental technician, Derek Cudlipp, to remove his four upper incisors and two upper left premolars and replace them with false teeth. To accentuate the slippage, Cudlipp used no archwire fasteners and left the upper left canine and the upper left molar unbracketed.

Later, when the young dental technician received his draft papers, Churchill tore them up. Later still, when Cudlipp asked Churchill to let him join a regiment and do his part, Churchill said, “You do more for the war effort staying here by my side in England, repairing my dentures, than you ever could fighting at the front.”

This was true.

9.

From another O’Meara letter: “The Emperor suffers from spongy gums and the right side of the jaws is considerably swollen.” Napoleon finally took his surgeon’s advice and accepted to undergo the first surgical procedure ever performed upon his person—the extraction of a canine eyetooth from the upper right jaw. O’Meara had him placed directly on the ground—another first. “He was far from brave,” wrote Lieutenant Colonel Gorregner, secretary of Sir Hugh Lowe, who was under the impression that the tooth was “barely rotten and could have been filled.” O’Meara was forced to have Napoleon held in place by three men.

The emperor’s 14-year-old friend Betsy Balcombe—the only person allowed to call him “Boney”—is said to have exclaimed, upon hearing Napoleon recount the operation: “What? You complain of pain caused by a minor operation? You who fought countless battles and passed through a hail of bullets, and was injured a dozen times? I am ashamed for you. But, anyway, give me the tooth!"

10.

Cudlipp was kept perpetually busy. Churchill was forever throwing his dentures at people in cabinet meetings. He told his son that Churchill often put his thumb behind his teeth and ejected them, and you could "tell the situation of the war effort from the distance they crossed through the room."

He had four sets in active rotation.

Next month, one of them is to be sold at auction. Along with John Lennon’s toilet. Which, I promise, to never mention again.

Thank you for reading. Have a great week.

Teeth should have no nerves in them- it's cruel.

My first abscess was at your grad and I took 21 tylenol and ate a bag of ice.My date was a redhead(with a beard?)Charlie someone-he played rugby-he and I were the first to be announced as grad dates.I liked him-he was like an old Scottish man. That was the beginning of an epic tooth life.Today I floss and there is no drama.

When I go to the dentist all I do is hope to get a nice free toothbrush.