Blood purity (triptych)

"Sovereign is he who decides on the exception." – Carl Schmitt, 1922.

What is beauty? Once, while Goya was walking towards the deafman’s farm alongside a copse of oaks, he spied in a nearby wheat field – early evening, a Sabbath day, he had been drinking all afternoon at Moratín’s club, the sun was beginning to slip lower than the pink and blue hills in the beyond – and there he saw it, a circle of naked women dancing, and she, his Leocadia, at the centre, moving and swaying with such energy and abandonment that it made him stop in his tracks, whereby he saw some of the women to have satyrs’ feet, cloven feet like oxen or goats, and he being astonished with shock and awe did cry out, and laugh, and say Mary, mother of God. And no sooner had he said this but they all vanished except her, his Leocadia, la brujita, whom a little after he saw snatched up into the air, and his self was also driven so forcibly with the wind, that it made him almost lose his breath, and he woke up face down in the flattened wheat.

His pen, now, in his hand, leaking cuttlefish ink onto the desktop. Mosquitoes whine around his unregenerate head, which for a full hour has rested awkwardly on his folded arms. How many pictures persist inside the wretched thing? Does it still house visions? Can any be unseen? An image is an idea, he supposes, or near enough, and visions, too, imagined out of nothing, from something eaten or drunk, or a story told. The latter rarely happens anymore. Communication with his outside world, beyond the chalkboard around his neck, all but finished. What is good, what is beauty, all signals, even the whining buzz of the blood-feeding insects in the room, are blocked by the ringing silence in his head.

And yet still the pen is in the hand and the mosquitoes hover and whine. One spirals down onto the exposed skin of his arm, just above the cuff of his coat. He feels its weight and its bite, and he opens his eyes to it, and pinches the skin with his fingers on both sides of its mouthpart, and watches it engorge on his blood until it explodes. A being, now vaporised, leaving an angry, itching welt. Is it evil? The insect, its killing or the welt? Is viscera and excrement evil? Where is the sin, is there sin? They are not forms, these are things that we see, without contrary, part of the natural order.

The smug stench of it,

my dream’s last leaf as it falls,

one last parting fart? – Kyöon, 1234The sketch is of a bear at first. He has an image of it attacking a man, the bear of Madrid, up on its hind legs, shaking scarlet red berries with creamy-white bells from an arbutus tree – the strawberry tree, el madroño, which Bosch planted in The Garden of Earthly Delights next to a three-headed lizard and a three-headed bird, a two-legged dog and a monkey on the back of an elephant.

According to Aristotle, after at least forty days and nights of hivernal concealment, the starved bear’s first course of action is to feed on the roots of the wild arum lily, which distends the bear’s emptied belly, causing it to expel whatever noxious spirits found roost therein during the long long winter.

This idea appeals to Goya. He is not sure why.

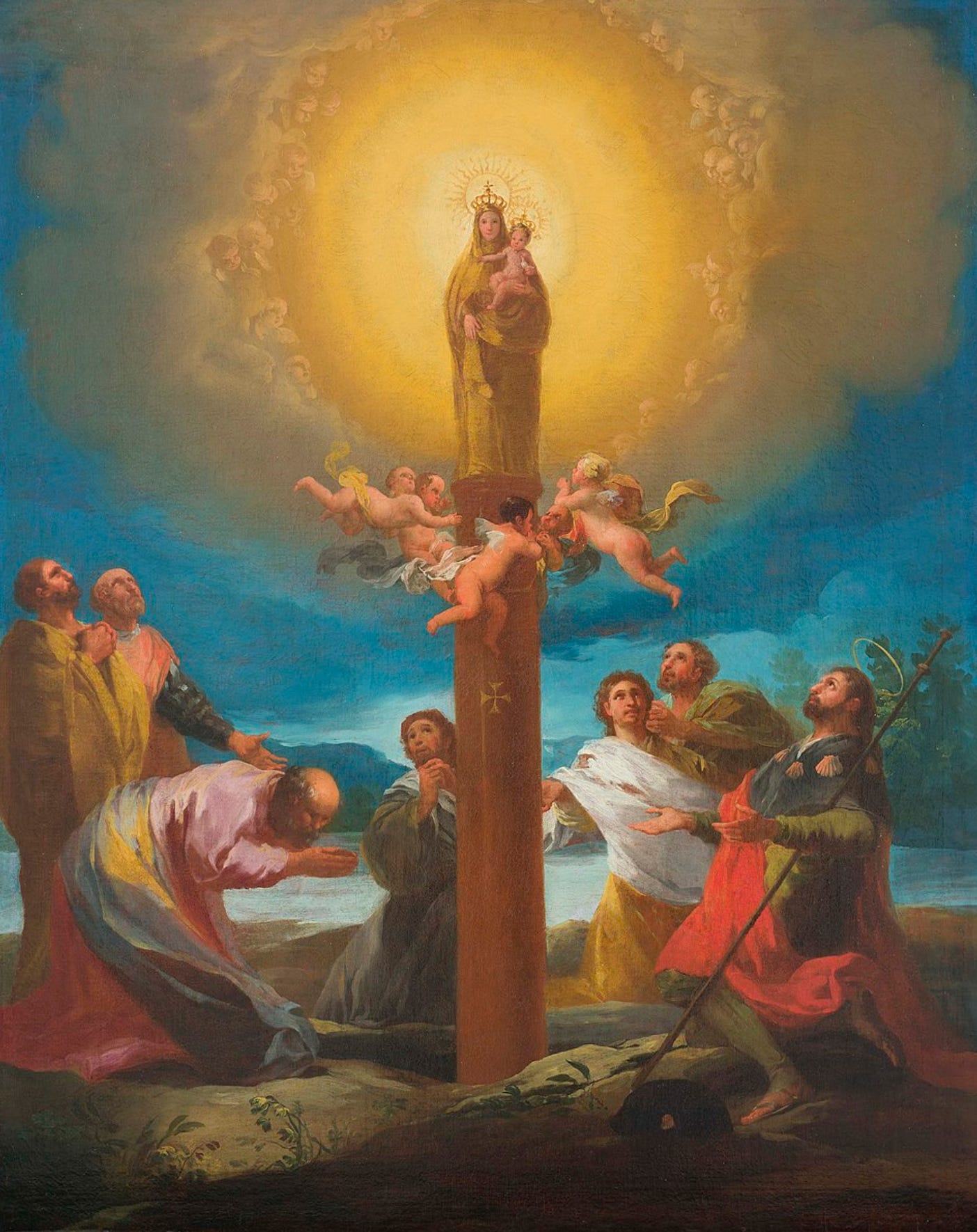

Later this night, though, for the first time since he was abandoned to his suffering during the darkest days of his enfeeblement, now six years old but still fresh as a new wound, the Virgin Mary came to him – or rather, he saw the Virgin Mary, or a vision of the Virgin Mary, draped and crowned in gold and standing on the blood-red pillar on which she first appeared to the Apostle on the bank of the river in his hometown. As a child, at the urging of his mother, he waited in line for hours every feast day to kiss this same pillar – the Virgin Mary and her host of angels left it behind as testimony of their visitation – through a tiny oval-shaped opening in its red velvet mantle. As a man he represented it in countless sketches, prints and paintings, including the frescoes on the vaults and domes in Ventura Rodríguez’ new basilica chapel, which replaced the chapel of his childhood, itself the third replacement of the chapel that replaced the chapel that replaced the chapel that replaced the original chapel built by St James on the very spot on the river that he first saw this jasper pillar, with the immaculate mother of god standing upon it, garbed in the light of the sun, her arms opened wide.

The deafman’s farmhouse is plain and square. It has none of the cathedral’s highest art, where each of its thousands of details is beautiful in itself, each whisper of beauty echoing the next, all similar, converging as one to serve the greater unity of the whole. In the natural order, too, from the simplest polyp, a mindless, vase-shaped sac with a maw, to the highest, man, the most complex. If you cut the polyp into pieces, as he has done, each piece lives. Turned inside out, its skin becomes its stomach, and vice versa. Every part is interchangeable with every other part with indifferent facility, a democracy of organs, for none is essential, each is sufficient unto itself. In man, however, ever glorious, every part is assigned its distinct office, every organ its irreplaceable role. That is the highest form, the form of unity, wherein the manifold serves the one, and the one is glorified by the manifold.

What is good? What is beauty? He is besieged. No rules can be laid down. Asleep again, his dream again agitated by the blood-red pillar of El Pilar in the Cathedral in Zaragoza. It is the most kissed rock in the world. In the future, more than a hundred years after his death, aerial bombs will drop on it, but miraculously, it will not explode. A new thought surges: the world destroyed most of his Marys. His first commission, paintings of the Blessed Virgin in the Sacristy cupboard of the parish church of Fuendetodos, were destroyed by anarchists. The French destroyed his Immaculate Conception with their sabres in the church of the College of Calatrava in Salamanca. Elsewhere, in churches and cathedrals, most are so darkened by candle soot you can’t see her figure.

To him, again, this is what he says to himself inside his slumber, the polished red pillar looks like raw meat. Again, he stops this thought and replaces it with the pillar of jasper, held aloft on a billowing cloud by a thousandfold of angels. This is more satisfying, more beautiful and good. Mosquitoes circle and whine, the bite grows itchy and enraged, but he is consoled, reconciled with Our Lady of the Pillar in the fold and embrace of righteousness and faith, and held aloft, like Mary herself, the Virgin Mother of God, the Queen of the Martyrs, she who is at once here and eternal, with him and in him, passed beyond death and judgement and living wholly in the Age to Come and in his deafman’s farmhouse and the Basilica in Zaragoza and on the bank of the Río Ebro in Caesaraugusta, now known as Zaragoza, the capital of the Kingdom of Aragon, with the Apostle James – the taller Apostle James not the shorter James who is the brother, half-brother or cousin of the son of God, but James the Great, the son of Zebedee and the brother of John, on his knees on the floor next to the table, trying to trim his lamp and failing, praying to the Virgin Mary and failing, converting the heathens of Hispania and failing.

James, forget your lamp, this is what his unregenerate head is now saying, and lift your eyes, lift them up to the apparition before you, look with mortification and fear upon the immaculate mother of God, the Virgin Mother, multilocating before you four years before your decapitation on a cloud carried by angels. This is Beauty and this is Good, and there is no other light, no other guide, for this is the only miracle. This is the image he should render once again. Mary the Virgin Mother of God, the Queen of the Martyrs, the new Eve, Our Lady of the Bloodstone Pillar, draped head to toe in golden garments and standing on a pillar of red jasper marble that looks and smells – stop! – like red meat, clutching absent-mindedly in her limp left the chuckling baby, whose bald unhaloed head is monstrously huge and as wrinkled as an old man’s – stop! – ball sack.

Something is urgently wrong. He tries not to see it, not to think it, he stares into the darkness, seeking the light which can only come from his soul, from his own heart, but that is presently shadowed by darker clouds, unobservable and obscure, for what he sees instead are donkeys; he sees that the angels carrying the cloud are donkeys, reared up and dancing on their hind hooves.

It comes from the hill out of which this stone is taken, this red bloodstone, which dwelt and was situated upon Mount Sion in Jerusalem, and this stone was produced without hands, without man's seed, without man's help and nature; it came out of the foresaid hill; for the Christ took his flesh from no earthly father, but only of the substance of Mary his mother, of whose breasts the said flesh was nourished afterward. Christ was conceived of the Holy Ghost, not the Father; and like all loving mothers Mary kissed the chuckling baby Jesus on the mouth and wiped his shitty bottom. Did not the Lord create this hostile carousel of lust and love with his own hands? Which is worse, a handful of hours spent on the cross or nine months cooped up in the womb of an adulterer, like an anchorite in his filth-filled cell? Who can bring a clean thing out of an unclean? No one. Surely I was brought forth in iniquity; I was sinful when my mother conceived me. So many Marys. A lifetime of Marys. Now, in a blue gown with her hair unbound, reading from the Book of Hours, oblivious to the Holy Ghost impregnating her. Joseph oblivious in the next room, impotently drilling holes in a plank of wood, the back of a cuckoo clock – or maybe a mousetrap, or a spiked stumbling block that gashes the legs of the punished sinner who walks with it hanging from a cord around his waist, he has seen these used by the Holy Office – oblivious to the Holy Ghost drilling his wife-to-be next door, fulfilling and enflaming her with the love of God more burning than ever before, and feeling that she had conceived, she kneeled and thanked God as her womb trembled and swelled at the touch of the Holy Ghost, and her knees buckled, and her spirit rejoiced, and her womb flowered. And in the next panel, his patrons, the Osunas, are down on their knees in the garden praying and peeking through the half-open door at the divine infusion, the immaculate incarnation. He thinks of a painting, maybe an etching, of Bernardo de Claraval, kneeling and praying before the apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary holding the chuckling infant and squeezing one of her breasts, squirting breast milk in a geysering stream into his mouth, granting him wisdom, and into his eyes, curing his infection. For the infection is sin and ignorance, and the milk of the Blessed Virgin cures it, bestowing upon him pure sight and the illumination of wisdom.

Stop.

He was once a crack shot, but he hasn’t hunted animal flesh in seven years, since his sickness. He misses the copses and streams of Aragon. He misses the smell of blood-dampened fur.

The bear again, he tries not to think of it, and yet the cursed thing comes to his mind.

So many animals. Stags, cows, wild boars and birds. How many has he killed? Eighteen in a single day, a rabbit, two hares, five partridges, and ten quail. His best day ever, and only one shot missed.

The last time he was out, he killed fifty-four birds to the king’s four. This mattered more than how he dressed, what he thought, or what he read. His views are his own, but they change; they vary depending on the rank and discretion of his company, just like his clothes and his hats. How or why, he is not sure.

He does not know if there is more to things than meets the eye. He repeats little prayers to himself, he makes the sign of the cross every day and he draws crosses at the top of his letters, along with hearts and cocks and balls.

Does he believe? He sees faith as a palliative, a way to whet and curb the appetites. This world, this hell and heaven, not the next, with his two living children and his nineteen dead, is more than enough.

He is conservative in some ways, liberal in others. In all things, he is discreet; this is the key to his success. Not his success, his survival. He has acquaintances on every rung of every social ladder, and he calls them all by their Christian names.

He thinks of Bosch again. Bosch, the forest, the dark wood. Hieronymus, after St Jerome the ascetic, who spent his time in Rome surrounded by women in the pursuit of his lust for nothingness, and in the desert hiding from them in his quest for plenitude and bliss.

On the puddled paper beneath his head, a phrase from Horace:

If a painter chose to put a human head on a horse’s neck and multi-coloured feathers on a jumble of limbs, so that a beautiful woman at the top ended repulsively in the tail of a black fish: asked to view such a work, could you hold back your laughter, my friends?

The bear becomes a pig-horse, lying on the road, covered with flies, its bloated belly pooled out in the dirt. There is hardly any light left in its eye. The fight in it, its monstrous fierceness, is gone. Naked corpses disgorge from its mouth. The stench is overpowering. Where did it come from? From last night’s indulgences?

There is no potential to corrupt if everything is unseen, locked away. So this is what he does when these things come to him, when they haunt and infest, when they dwell inside. He releases them, pushes them out into the world. The inside thing, the thing imagined, the monstrous thing, he makes it manifest. Turns it into drawing. Prepares the plate, bites it with strong water, makes a single print. And then he puts it all away. Hides it and its consequences. Shuts it up inside a wall.