The dead centre of town

Steady the trot to the cemetery, duly rattles the death-bell,

The gate is pass'd, the new-dug grave is halted at, the living alight, the hearse uncloses,

The coffin is pass'd out, lower'd and settled, the whip is laid on the coffin, the earth is swiftly shovel'd in,

The mound above is flatted with the spades — silence,

A minute — no one moves or speaks — it is done,

He is decently put away — is there any thing more?

— Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman, 1855For the last few days, I have been steadily trotting, despite an aching Achilles, through the city I was born in, Vancouver, British Columbia, while staying in a beautiful house-swap house on a street surrounded by the Telletubbyland of tombs pictured above.

It has been a marvellous stay. The house has breathtaking views of Grouse Mountain from the front window and a tidal bed of submerged corpses from the kitchen. I have immeasurably enjoyed contemplating death while eating breakfast. But something is missing. Actually, two things: nowhere among the 95,000 graves and 145,000 interred remains can I find, online or on my morning runs, my mother’s parents, who my sister thinks are hidden there. Naturally, this is honing what little focus remains on my own beginnings and end and away from my middle, which, over the holidays, has taken on Jackie Gleasonesque proportions and sees itself — and is seen as — the meriting centre of all attentions.

My grandmother, Linda Stephenson, née Angel, was born in 1880 in Heart’s Content, Newfoundland.

I vaguely remember her long white hair and that she smelled nice and was kind until dementia set in, whereupon my memories get very loud and screechy. Apparently, according to my other sister, her derangement was triggered by her arrest for jaywalking on Davie Street. Whether this is true or not I cannot know.

She died in a home in 1972.

Her father, Isaac Angel, was born in Tottenham, London. I think his parents were Polish and that his father was a boot riveter. I’m not sure why I think this, nor can I find any corroborating evidence in my notes.

When he was a small boy his family moved to Guernsey, where I’d like to believe he met Victor Hugo and, like Hugo, had his photo taken by Julia Margaret Cameron, whose photographs I saw in an exhibition at the Jeu de Paume in Paris just before the holidays.

Perhaps this is him in the top left corner of the photograph below, posing with Cameron’s daughter and her friends.

In 1866, the year this photograph was taken, Isaac emigrated to Canada aboard the SS Great Eastern. During the voyage, the first transatlantic submarine cable was successfully laid on the Atlantic floor. The boat docked in Heart's Content, where Isaac secured a position in the cable office. Perhaps he was already employed by the cable company when it set off from Valentia Island off the west coast of Ireland. Or even before. He later rose to the rank of Director.

My grandfather, George Arthur Stephenson, named after the “Father of Railways”, was born in 1886 in Stockton-on-Tees in Yorkshire, the birthplace of the friction match and the first steam locomotive. He was a telegraph operator in Hazel Hill, Nova Scotia, which is where he met my great-grandfather and my grandmother, and where he lost his eyesight, or most of it, reading cables by candlelight and under blackout conditions during the two wars. After his retirement, he and Linda moved to Vancouver, and after Linda’s death he lived with us. He was a great storyteller and a very good cribbage player, though I never lost a game to him, as I could see his cards reflected in his eyeglasses.

Dementia took him too. I remember the night it began. He and I were alone in the house and he came into my room where I was doing my homework, and I was shocked to see him shirtless, a state in which I had never seen him before. He demanded that I take dictation, as “things were beginning to happen” involving kings and queens and animals, and strange birds that were watching him from the park across the street, and all because of the days he spent as a boy in his father’s public house in Liverpool — my mother had no idea her father was a publican, and was very distraught to learn this — and then he stripped off the rest of his clothes and, when I wasn’t looking, headed off out the door and up the street.

He died in a home in White Rock in 1980.

We leave tomorrow for Paris.

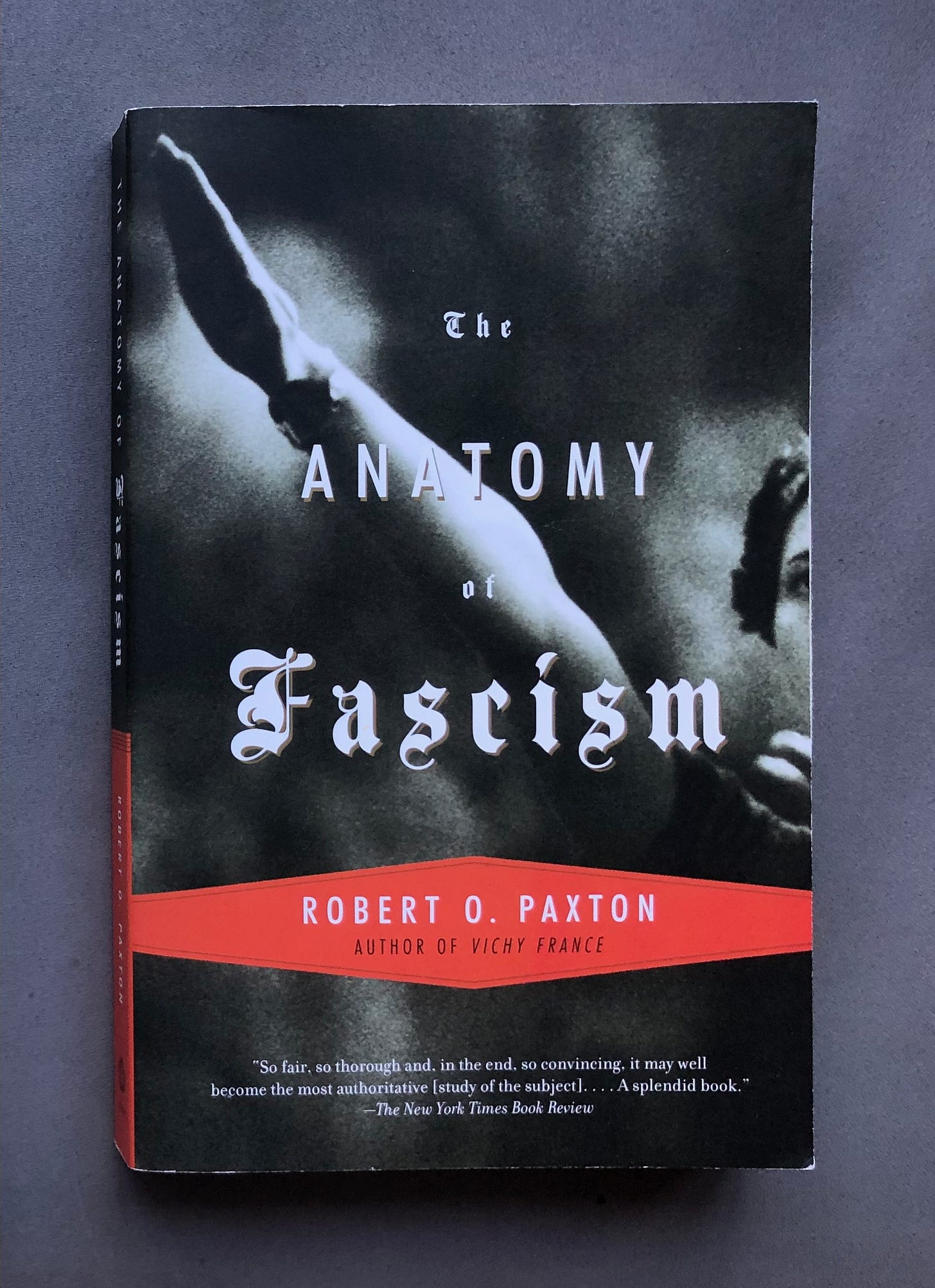

In our luggage are the many books we purchased from the great new and used bookstores of Victoria and Vancouver, including this one picked up yesterday at Pulp Fiction on Main Street:

and everyone else on both sides of the recent “Substack has a Nazi Problem” problem: this is essential reading.Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victim-hood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.

Sounds like today all over again, doesn’t it? Also essential is the essay by the 91-year-old Paxton on the Pétain trial in the most recent Harper’s. Reading these this week and visiting the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library's Treasures a couple of weeks ago have restored my faith in history and my love and admiration for the American Republic.

I bought the Paxton at Pulp Fiction Books, Chris Brayshaw’s excellent bookstore on Main Street.

Chris and I worked together at the long-gone, employee-owned Granville Book Company back in the late 80s, along with Rod Clarke, who now co-runs the spectacular Pender Street bookshop, The Paper Hound.

I still try to see Rod on most trips to Vancouver, but I shy away from direct encounters with Chris, as I angered him, along with many other culturally engaged Vancouverites, when I wrote a somewhat glib piece about the city and its contemporary art scene a gazillion years ago for Modern Painters. The offending piece, “Peripheral Visions: Art and Lifestyle in Hollywood North” started with this paragraph:

Terminal City, Lotus Land, Smug Harbour, The Sanctimonious Marina, the Crack Capital of Canada. The names don’t hurt; even Vancouver’s most cosseted and cosmopolitan wear their end-of-the-line, rough-and-tumble fringe status with insular pride. Nor do sticks and stones break their bones; they pay the bills — forest and mineral products are the city's major exports, followed closely by fish, grain, “BC Bud” marijuana and, from a critically detached distance, conceptual art.

And so on. I’ve been ostracized ever since.

There are few, if any, public garbage cans in Vancouver.

At this time he found everywhere objects already known to him but marvellously mingled and mated, and strange vicissitudes often arose within him. Soon he became aware of the inter-relation of all things, of conjunctions, of coincidences. — Novalis, 1798

The BC Bud market has changed, as there are government-sanctioned cannabis shops on every street corner, and mushroom-LSD-peyote dispensaries in the middle of every block, surrounded by brewpubs and cocktail bars that fill at noon and stay filled well past midnight. This is not the city I grew up in. This city is lit up.

Then there’s the coffee. Thankfully and inexplicably the Starbucks have dwindled, but there are good coffee spots everywhere. My favourite this trip is Oidé on 2nd Avenue, run by a Japanese couple who used to pull shots (sorry) out of a window on Carrall Street, in the darkest horror-core of the Downtown East Side. Now it’s off Granville Island in the Waterfall Building, designed by Arthur Erickson, where many years ago, while drinking bubbly and conversing with Leah McLaren (Juvenescence) at a wedding reception, I fell into the reflecting pool.

And, as everywhere of late, there are dogs. Almost everyone I encounter during my runs has one at the end of a leash in one hand and, because of the absence of garbage cans, a biodegradable bag of its shit in the other. Often, they’re also juggling a giant cup of coffee. And a huge skunky spliff.

Which category do dogs fall under? Are pets part of the animal kingdom or do they belong more properly to the empire of man? There are very few epithets worse than “dog” in most parts of Africa. Their “owners” do not give them toys and treats. They do not eat out of dedicated food bowls. They are vectors of disease, raised to guard or as sacrifice fodder. Nothing more. They are never allowed inside a home.

Or this is what I have been led to believe.

In Shinto, the Inugami were malevolent spirits conjured forth through the ritual sacrifice of pet dogs. The dog-tormented spirits could then be controlled by the people who summoned them forth — to do their bidding, spread misfortune, or curse and possess other people. This for some reason has fallen out of favour in Japan I am told (my daughter just spent six months there, but she is not the source of this information). Dogs are now considered family, they wear designer clothing and are memorialized in household shrines, alongside ancestors. Dog remains are displayed in expensive funeral urns, in specially designed columbaria.

It is worse than here there now.

My favourite tombstone

Would that that would one day be said of me — as opposed to this, said by Alexander Dumas, in 1858, of the painter Gustave Courbet:

From what fabulous crossing of a slug with a peacock, from what genital antitheses, from what sebaceous oozing can have been generated, for instance, this thing called M. Gustave Courbet? Under what gardener's cloche, with the help of what manure, as a result of what mixture of wine, beer, corrosive mucus and flatulent edema can have grown this sonorous and hairy pumpkin, this aesthetic belly, this imbecilic and impotent incarnation of the Self? Wouldn’t one say he was a force of God, if God — Whom this non-being has wanted to destroy — were capable of playing pranks, and could have mixed Himself up with this?

My father loved Jackie Gleason.

Jackie Gleason had many radio hits and released 70 albums of easy listening pap. My father owned many of them. Most were composed and arranged by Bobby Hacket, who Gleason paid scale. Bobby was a good trumpet player in the Bix Beiderbecke tradition, but dental surgery ruined his embouchure, so he stuck to short solos or played guitar.

My grandfather did not think much of Jackie. I was of mixed opinions but impressed to learn that he could vomit on cue, and that his 300 pounds of embalmed blob are entombed in a white marble sarcophagus in a private mausoleum at Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Cemetery in Miami, near the golf course where he, Richard Nixon and Bebe Rebozo played. And later Ford.

The later model Ford.

The Gleason sepulchre dwarves everything else in the cemetery. Corinthians columns under the portico and pediment facade, engaged columns embedded all around, and the words “And Away We Go” etched into the riser of the third marble stair from the top.

It is modelled on the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, which Henry James’s describes standing in front of — it has been a tourist destination for centuries — “first in the evening, in the vague moonlight, which made it look as if it were cast in bronze.”

One is most struck by its familiarity. The first impression you receive from this delicate little building, as you stand before it, is that you have already seen it many times (my italics). Photographs, engravings, models, medals, have placed it definitely in your eye, so that from the sentiment with which you regard it curiosity and surprise are almost completely, and perhaps deplorably, absent (my italics).

Nobody went to Gleason’s funeral. He was a self-centred boor and a mean drunk, a small-minded, insecure prick who short-changed everyone around him, who took pride in his ability to humiliate, and whose favourite party trick was throwing up on the person next to him.

Bob Hope and Perry Como sent flowers. Nixon did not.

Whitman the hitman

Where the mocking-bird sounds his delicious gurgles, cackles,

screams, weeps,

Where burial coaches enter the arch'd gates of a cemetery,

Where winter wolves bark amid wastes of snow and icicled trees,

Where the katy-did works her chromatic reed on the walnut-tree

over the well. — "Leaves of Grass", Walt Whitman, 1855Leaves of Grass, penned no score and seven years before Courbet painted the picture above, which, on May 5, 1941, was seized from the home of a prominent Jewish family in the 16th Arrondissement of Paris and taken to the Jeu de Paume, where it was presented to Hermann Goering, the President of the Reichstag and Hitler’s designated successor.

In 1945, it was found in an underground cache in the Berchtesgaden Alps. It then disappeared for six years, before resurfacing on the Swiss art market, where it was purchased, then bequeathed, by the Reverend Eric Milner-White to the Fitzwilliam Museum, of the University of Cambridge.

Last year (last year!), following a decision by the United Kingdom’s Spoliation Advisory Panel, the painting was returned to the heirs of its rightful owner.

“This is a deliberate seizure by the German authorities from a Jewish citizen of France with the diversion of the work of art to Nazi leaders,” the panel wrote in its report, which can be read here:

Hitler’s paternal grandmother, Maria Schicklgruber, was variously described in the literature as “maid”, “cook” and “unmarried servant girl”, though she was 42 at the time of her only child’s birth. She died of “consumption in consequence of thoracic dropsy" in Kleinmotten, near Strones, in Austria, in 1847, nineteen years after the death of her husband. She is buried at the parish church in Döllersheim. Or rather, she was buried there. The Döllersheim cemetery was destroyed by German tanks when, following the annexation of Austria in 1938, Hitler ordered the birthplace of his grandparents converted into a training camp for the Wehrmacht. Not a single building was left standing. His grandparents’ bones were ground to dust.

This is probably not true. Or only partially true.

Come tell us old man, as from young men and maidens that love me, (Arous’d and angry, I’d thought to beat the alarum, and urge relentless war, But soon my fingers fail’d me, my face droop’d and I resign’d myself, To sit by the wounded and soothe them, or silently watch the dead.)

Walt Whitman the Wound Dresser, silently watching the dead. Except he was hardly silent. Nor should we be. He spoke, he filled notebooks, he sang his electric songs and raised the multitude that is America.

I speak the password primeval, I give the sign of democracy, By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms. Through me may long dumb voices, Voices of the interminable generations of prisoners and slaves, Voices of the diseased and despairing and of thieves and dwarfs, Voices of cycles of preparation and accretion, And of the threads that connect the stars, and of wombs and of the father stuff, And of the rights of them the others are down upon, Of the deformed, trivial, flat, foolish, despised, Fog in the air, beetles rolling balls of dung. Through me forbidden voices, Voices of sexes and lusts, voices veiled and I remove the veil, Voices indecent by me clarified and transfigured. I do not press my fingers across my mouth, I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and heart, Copulation is no more rank to me than death is. I believe in the flesh and the appetites, Seeing, hearing, feeling, are miracles, and each part and tag of me is a miracle.

Fog in the air, beetles rolling balls of dung. In mid-December, 1862, Whitman was swept into the maelstrom of war by his younger brother George Washington Whitman, a breveted lieutenant colonel whose name was listed in the New York Herald among the 15,000 casualties of the Battle of First Fredericksburg.

George had survived Antietam in September of that year, where more than 23,000 were killed, wounded, or missing — buried uncounted in unmarked graves, often right where they fell — but at Fredericksburg he was levelled by an errant volley of musket shot to the jaw.

Whitman arrived in DC penniless, he had been pick-pocketed on the train, but through friends, he found a way to slip behind the lines, and on December 29, 1862, he wrote to his mother to say that he had “found George alive and well” among 3,000 other casualties in a wharf-camp across the river at Falmouth (westward from the I-95 bridge). He also told her he was staying behind to nurse the wounded.

Straight and swift to my wounded I go, Where they lie on the ground after the battle brought in, Where their priceless blood reddens the grass, the ground, Or to the rows of the hospital tent, or under the roof’d hospital, To the long rows of cots up and down each side I return, To each and all one after another I draw near, not one do I miss.

I enjoy cemeteries, as you now know.

I have visited many, including the island cemetery of Venice, where I paid respects to Ezra Pound and Igor Stravinsky. That cemetery was created because of a Napoleonic edict, which called for all cities in the Empire to bury their dead citizenry outside their walls. The Freemasons were the first Europeans to obtain official recognition for the incineration of the dead, around 1860.

My favorite in America of course is Arlington. My favorite on the West Coast is the New Calvary Cemetery on Whittier Boulevard in Los Angeles, which replaces the Calvary Cemetery for Roman Catholics on North Broadway. There are two Jewish cemeteries adjacent to it: the Home of Peace on Third Street and Mount Zion on Downey. When the new Calvary opened in 1896, as many bodies as could be unearthed and reassembled from the original site were moved to the new one.

Cathedral High School was built on the grounds of the old Calvary cemetery. The school’s sports teams are called the “Phantoms.”

As you can also tell, the burden of my corpse is weighing heavily on mind.

How will it be disposed? Incineration and burial both have advantages and disadvantages. After earthquakes, local officials, ostensibly fuelled by public concern, often rush to burn, but this is based on unfounded notions of hygiene. The dead are not dangerous, pathogens prefer the living, they will not survive long in a cadaver. Still, cremation is arguably the more rational form of elimination: it wastes fewer resources and accelerates the dematerialization of the body. The dead arrive in the land of shadows in an hour and a half. A body preserved in a box and buried in the ground breaks down anyway; why not expedite the process? Composting, I now hear, is a thing. I passed a sign on Highway 4 that read “Natural Cemetery”. And I saw a tombstone out the kitchen window that either read “Everyone was touched by him” or “He touched everyone.” Not without virtues either.

Until the end of World War II, only monks and the wealthy were cremated in Japan; everyone else was buried.

After the war, in part through the efforts of the USIS, cremation became more common. It is cleaner and more efficient. Nowadays, except in extreme circumstances, burials are very rare. In many towns and cities, it is illegal. The earliest written record of cremation in Japan refers to the priest Dosho (d. 700. or the 4th year of the reign of Emperor Monmu).

In 1880, the year of my maternal grandmother’s birth, an ascetic, after a thousand-day process of mortification, threw himself in lotus position from the top of the Nachi falls. His body was found at the bottom of the cascade, still in the posture of meditation. It is now buried in the cemetery of Nachi.

“Once you get into this great steaming stream of history you can't get out,” said Nixon.

“You can drown. Or you can be pulled ashore by the tide. But it is awfully hard to get out when you are in the middle of the stream — if it is intended that you stay there." He told this to Earl Mazo in 1959. A year later Earl found a cemetery in Chicago where every tombstone name had voted Kennedy. “I remember a house,” he wrote in his exposé. “It was completely gutted. There was nobody there. But there were 56 votes for Kennedy in that house.” Nixon pulled his plug after four instalments in the Herald Tribune. “Earl, this is a moment of crisis,” he said. “We can’t afford a vacuum in leadership.” Earl thought he was kidding.

In a Japanese crematory, the ovens are maintained at significantly lower temperatures.

The goal in Japan is not to reduce loved ones to a fine powdery dust but to hold on to a few of their most significant bones. These are essential to the second stage of the ceremony: after the cremation (which is viewed through a round window in the crematory door), mourners are led by the priest to the bone-picking room, where they pluck the surviving fragments from the ashes with pairs of unusually long wooden chopsticks. A bone expert aids them by identifying the fragments and calling out their names — tooth, jaw, toe, collarbone, fibula, and so on. The remnants are collectively scrutinized and then placed in squat metal urns. Often, two relatives will take hold of the same bone at the same time or pass them from one set of chopsticks to another. This is only permitted at funerals, never during meals. Passing food from chopsticks to chopsticks or grabbing hold of the same morsel at the same time with two sets of chopsticks is considered rude.

Feet bones first, head bones last: you never put a person in his urn upside down. Or his urns: sometimes a body will require more than one urn, even though the bone expert uses a space-saving crusher to flatten the remains to make extra space.

Mourners in the bone-picking room have been known to warm their hands over the glowing embers of their dearly departed.

You cannot accelerate history, you can only exploits its currents.

My ability to test the reality of this has been compromised. I am exhausted, confused, cut off, a half-starved pilot flying solo over the Atlantic, no bearings, no up or down, sky or ocean — my cortex is fog-bound. Fog in the air, beetles rolling balls of dung.

A strong desire, a Bach melody, the smell of my mother’s purse, my wife’s new perfume. Stronger than fasting, hallucinogenic drugs, ataractic drugs, surgical cingulectomy.

The rest is a rat’s nest, pure tumult, the dead man’s graveyard spin. It is an old trick of the brain, aided and abetted by the inner ear: the wings are level, but it feels like you are descending, that you are falling out of the sky. You pull back on the controls, tightening the spiral and increasing the drop. The fluid in the semi-circular canals of the inner ear stabilizes, you think you are holding steady, no longer accelerating, the sensation-sensing organs balance out, you turn your head to look at a chart, change tanks, pick something up off the floor. If you keep sight of the horizon, fine, then there’s no problem. If you don’t, you’re better off on autopilot. Tune in and turn on —don’t drop. And as soon as you’re stable, flying along stable, heading toward the lights on the coast, do an about-face. Crank the controls 180 degrees, fly back to safety. Head out to sea.

Welcome to 2024.

There's a great bit in the first chapter of 'Underworld' where Gleason, Sinatra, and Toots Shor are in the stands for the famous '51 'shot heard round the world' game. Gleason, getting progressively drunker while J. Edgar Hoover looks on from mere rows away, does his business all over Sinatra's shoes: “Jackie utters an aquatic bark, it is loud and crude, the hoarse call of a mammal in distress. Then the surge of flannel matter. He seems to be vomiting someone’s taupe pajamas."

And a bit later, Gleason says: "Hey. Don't think you're the first friend I ever puked on. I puked on better men than you. Consider yourself honored."

"The goal in Japan is not to reduce loved ones to a fine powdery dust but to hold on to a few of their most significant bones. These are essential to the second stage of the ceremony: after the cremation (which is viewed through a round window in the crematory door), mourners are led by the priest to the bone-picking room, where they pluck the surviving fragments from the ashes with pairs of unusually long wooden chopsticks." -- A similar ritual is depicted in the Apple series, Drops of God (French production, not the earlier Japanese manga series). Have you seen it?