For the last five years, I’ve had a very intense relationship with a man in his early 30s. No, not like that. He knocks on my door, I open it. I don’t invite him in. After a brief exchange, I either tell him to wait or I close the door. Once, when the door was open and my back was turned, he crossed the threshold and sat down at the kitchen table. I told him to go back outside. Another time, he sat on the doorsill, half in, legs out. I let him stay there while we conducted our business, but it made me uncomfortable. As it did my wife. “Don’t let him inside,” she said later. This is not because she is mean-spirited. This is because he is filthy and smells like shit.

“He probably has bed bugs,” she said.

Lice, too. He scratches a lot.

“‘Do I look like someone who has something to do here on earth?' That's what I'd like to answer the busybodies who inquire into my activities.”― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

We met in the late spring of 2017, during an al fresco dinner party in front of our building—our apartment is in Belleville, the main floor is a converted storefront, the front door opens onto the sidewalk. He stumbled past the table wild-eyed, shirt torn, shoes blown, hands, arms black with grime, a gash over one eye. Hearing our conversation, he laughed and shouted “English!” and lurched towards us.

“Can you give me some money? And a beer or something? I’m from Canada! Where you guys from?”

He was from “Toronno”. Toronto accent, same as two people at our table, one of whom went to his high school. “Get the fuck out,” he said, “that’s amazing! Did you have, uh, Mister, uh, Mister what was his name?” His eyes went blank and he wiped and scratched his face, smearing blood and grime across his forehead. “Stanley! Mister fucking Stanley! What a dick that guy was! Man, I miss Toronto. Sort of. Parts of it.” He zoned out again, deeper this time, then scratched his scalp, stopped, zoned, checked his pockets, pulled out a bunched-up piece of paper and some coins, un-balled the paper, read it, counted the coins, looked behind him, turned to us, zoned out again, and then, in a low whisper, said, “I came to, uh, find my dad, do you know him? He’s, like, your age. French though, but really nice, you’d like him. He’s white, a white guy, like you. And he takes real good care of me and all, and he loves me, but, well, he lives with his, with his, uh, his wife who is, you know, kind of (deep cartoon voice) AUTHORITARIAN (long dry cackling laugh) and, just, I don’t know, they’re out in the countryside somewhere. Up north. A village. I’ve been there. Anyway, yeah, I don’t have his number. Well, I had it, but I lost it.”

He checked his pockets again, started laughing, off miles away in the zone. Then, snapping back: “You got any money, and a beer or something? And a cigarette?”

No one smoked. I poured him a glass of wine. Someone asked him where he was living and he said, “Oh, you know, around. Wherever I’m needed.”

“Needed? For what?”

“I help people,” he said, giggling. “I’m sort of like a superhero or something. I have, you know, powers.”

A friend, who works with schizophrenics, asked him his name.

“Fred.”

“Fred,” said the friend, “you need to get off the street and get some help.”

“Yeah, I know, I will. It’s ok.”

I offered him some food. “Nah, I’m good, thanks.” My wife told him we could take him to the Canadian Embassy. Or to social services. He laughed and shook his head and said, “Nah. Just some money, please.”

The friend who works with schizophrenics gave him a ten euro bill.

“Thanks, man!”

And off he went.

“I get along quite well with someone only when he is at his lowest point.” ― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

He was back the next day, of course. Twice. And pretty much every day since.

If the door is closed, he taps on it with a fingernail. He used to pound on it but I told him not to.

A month ago I told him that he can’t knock on my door at midnight anymore. A week later, I changed that to not after dark. “I won’t answer,” I said.

“You there?” he shouts, tapping the door. “Can you just open the door? I just want to talk to you for two minutes.”

I have never taken myself for a being. A non-citizen, a marginal type, a nothing who exists only by the excess, by the superabundance of his nothingness.

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

Just now, quickly calculated: over the past five years, in small increments, coins mainly, a few fivers, a tenner once or twice, I have given Fred around 2,000 euros.

He knocks, and unless it’s dark, I open the door. I say hello, he say’s how’s it going? I say ok. You got ten euros? I’ll pay you back when I see my dad. I laugh and say, you won’t pay me back.

His father—I’ve since met him several times, I’ll tell you about that later—has offered to repay me. I have refused. I’m not sure why. Before he retired, he had a BMW car dealership.

Fred says, c’mon man, just call my dad. He’ll give it to you. I say, should we call your dad? He says, maybe tomorrow. I close the door and walk away, or I half close the door and look for money in the apartment. Money that is almost never physically present in the apartment, or anywhere else in my wedges of the world. It’s also, by the way, increasingly scarce in its digital form.

Anyway, if I can’t find a few coins in the key dish or a five-euro bill in a pocket, I’ll look around for the next best thing—a pair of old shoes, some warm clothes. Useful things better than money for someone in Fred’s shoes; most people will say this, think this, as what money Fred gets from people like me gets turned immediately into cans of beer. Almost every time he knocks he has an open one in his hand. “Hey man, how’s it going? You got some money?”

Sometimes he’ll accept the useful things I offer, other times he’ll asks for something else, like a jacket. Once, by mistake, I gave him a favourite cashmere sweater, a gift from my wife, which I had mistaken in my cupboard for an older stained cotton one from Uniqlo. I’ve also given him food. He’s not too interested in food. You got any beer? he asks. Or wine. He knows I drink more wine than beer. I’ve given him both. Most people will say and think that neither of these is what Fred needs. And they’re right. But they are definitely what he wants. As, to be honest, increasingly, do I.

I’ve bought him beers at the cafe next door, while sitting at a table together on the terrace, waiting for his father to arrive.

“To be objective is to treat others as you treat an object, a corpse—to behave with them like an undertaker.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

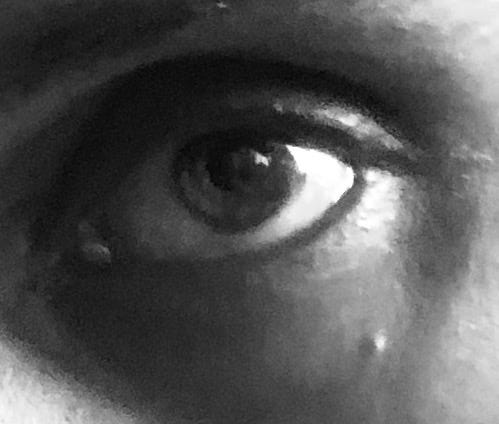

I’d like it if Fred, the Fred I know, whose eye that is at the top of this page—I snuck a photo of him last night—entirely disappeared. Seriously. Not die, just move on, get off the street, get his life together, or, failing that, just go somewhere else. Not because of the money and the knocking, and not because I don’t like him. I do, very much. I enjoy our conversations. Not the conversations where I get serious, get cross, rebuke him—I dislike these as much as he does. I enjoy the ones where he tells me what he has seen or found. Or what it was like being a roofer in Toronto, or sleeping in a laundromat. Or to live half your life—16 years—on the street. He doesn’t provide many details but he almost always has an interesting perspective, to say the least, and he likes to laugh and can be funny and quick-witted when he’s not too far gone. And he gives me stuff, coins he likes, special stones, bottle caps with special powers.

But. I’d much rather be deprived of these scant pleasures. I’d much rather not see him at all. Because seeing him, daily, is to watch him descend ever downward into a bleak and terrifying form of hell that he’ll never get out of because he doesn’t want to, because it’s what he prefers to any other form of life he’s known, and it’s frustrating to watch this and not be able to do anything about it.

“I have all the defects of other people and yet everything they do seems to me inconceivable.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

I know very little else about him. I know he wants to have children and be a dad, and he thinks he would be good at this because he’s good with kids, he takes care of them, he protects them. I know that he refuses to stay in shelters because of the curfews. Which is understandable. People who stay in shelters have to be in bed, lights out, at ten o’clock at night, and packed up and out the next morning by six. Some shelters force daily attendance at church services. Some, according to him, and I have no reason not to believe him, he often has black eyes and cuts on his face, are dangerous.

His father found him a foyer once. He left after a day. Another time, his father drove him up towards a clinic, to fill a prescription for a rash—Fred’s feet and shins are covered in burst blisters and open sores. Fred saw the clinic, opened the door of the moving car, rolled out and ran away. His father didn’t see him for a year.

Once, just next to my favourite bahn mi sandwich spot on rue de la Presentation, I saw him sleeping on a heating grate.

No, this is not a photo of him. Nor is this rue de la Presentation. Nor is his name Fred, but for the purpose of this—the purpose of which, as E.M. Cioran, if he were still alive (“It makes no sense to say that death is the goal of life, but what else is there to say?”) would no doubt tell us, is dubious at best—I will call him Fred, and his father Robert. I don’t know the names of the rest of his family, which, I believe, consists solely of a mother from Ethiopia, who now lives in Canada, a sister who recently moved back to France from Canada, who I met and will call Marie, and the stepmother from the Ivory Coast, who lived with Robert in Picardy, until her death last week, of cancer.

“If we could sleep twenty-four hours a day, we would soon return to the primordial slime, the beatitude of that perfect torpor before Genesis—the dream of every consciousness sick of itself.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

Across the street, sheltered by an ill-conceived overhang in a strangely recessed alcove on the ugliest building in the neighbourhood, a Polish man is sleeping under an overcoat in a puddle of his urine, next to an empty bottle of Pelure d'oignon rosé (2.75 euros at Franprix). I’ve never seen him with his eyes open. I don’t know his name, I’ve never spoken to him, I don’t give him money.

Yesterday, the Pole, whose name I don’t know, I call him the Pole because that is what the neighbours call him, yesterday he collapsed in front of the natural wine bar around the corner. The sommelier, Max, called the SAMU and their ambulance came quickly and took him away. His intake at the emergency room, which is just down the hill, was also probably quick, as he was still wearing the ID bracelet from his visit there two weeks ago. Max told me that. A neighbour told me that he was dead, but he’s not. He’s back, with a newly emptied bottle and bladder.

Other men occupied the spot before. I’m not sure where they were from as I never spoke to them. Nor did I give them money. They didn’t look or sound Polish and they didn’t piss themselves. I often saw the last two, younger men, maybe from Afghanistan, maybe Turkey, maybe Syria, seemingly close friends, clean, well-dressed, in possession of backpacks, hair combs, towels, and a small radio, washing themselves in a nearby Morris fountain.

They looked much healthier and happier than the Pole. They didn’t drink, they didn’t sleep in the day, they neatly packed away their belongings and disappeared until nightfall, when they would return, set up camp, turn on their radio, and listen to music and news programmes all night, in a language I couldn’t make out, until the batteries died.

I hated their radio and was happy when they moved on.

Before, there were three African men in the same spot, always gleefully fall-down drunk, laughing hysterically, or passed out together on the ground under a single blanket. I never spoke to them. I never gave them money.

“What do you do from morning to night?"

"I endure myself.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

I give money regularly to this man, Muhammed, the rose man, a 46-year-old Pakistani with four children—Aïza, Ayman, Alishtar et Menesh—and one front tooth. He has been selling roses in Paris for 13 years. He works long hours, till the bars close—drunks are his best customers—then returns to his home, a two-room apartment outside of Paris with no heat that he shares with eight other men. His wife and children are still in Pakistan.

I don’t know if Muhammed has papers, or was among the 467 Pakistani to apply for asylum in France the year he came (2010). Only 9.9% received refugee status that year. Last year, of the 2,959 Pakistanis that applied for asylum (down from 3,235 applications in 2020, which was 22% lower than 2019), 171 were granted refugee status and 55 received “subsidiary protection”.

According to the National Asylum Court (CNDA), asylum seekers from Pakistan came to France in 2021 for the following reasons: “thwarted love affairs (les amours contrariées), land disputes and persecution or discrimination suffered by religious minorities, particularly Shiites and Ahmadis.” Other applicants last year were female victims of trafficking, people in inter-faith relationships, people persecuted or disciminated for their sexual orientation and gender-identity, or for being Christian.

I'm not sure why Muhammed came. I've asked him, but I haven't understood his responses. He speaks only a few words of French and English. He communicates mainly by singing and smiling, holding up three or two fingers, looking comically sad or genuinely happy, and saying “merci” and “thank-you”.

A neighbour told me Muhammed was a political journalist in Islamabad.

I give him coins when I have them, he gives me one or more roses. He used to knock on the door until I told him not to. Now he sings outside on the sidewalk instead. If I don’t have coins his smile drops, but then he shrugs and smiles, and I say, next time, promis. Usually he waves and bows and gives me a rose all the same. Which my wife throws in the trash, still in its cellophane. In her defence, his roses have no fragrance. Out of the cellophane, they usually flop over and wilt almost instantly.

Happy times, when we had somewhere to run, when solitary spaces were accessible and welcoming! ― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

France is one of the three main destination countries of asylum seekers in Europe, with 103,164 applications submitted in 2021, putting it between Germany (190,000 applications) and Spain (65,000 applications)… Of the top ten countries of origin of first-time asylum seekers in France, only six (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Turkey, Georgia, Nigeria and Pakistan) are also in the European Top Ten. Côte d'Ivoire, which is the second most common nationality in France after Afghanistan, ranks only 17th in Europe. As for Guinea, which is the fifth country of origin in France, it is ranked 14th in the EU. France is, in fact, the first country of destination for these two nationalities, since it receives 64% of the Guinean asylum applications lodged in Europe and 73% of those from the Ivory Coast. Finally, 53% of the Albanian application, the thirteenth largest application in the European Union, is lodged in France.

(2021 Activity Report, OFPRA (French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons)

Canada is not on the above list, or anywhere in the OFPRA Report; nor is Fred an asylum seeker, or, for that matter, Canadian, though he grew up there, went to school there, became a roofer at 16, started smoking dope and drinking beer, had his first “episodes” and became homeless there. Fred is French, born outside of Paris in 1990 (I think). He never applied for Canadian citizenship. His father put him on a plane back to Toronto a few years ago, “it’s what he wanted so I said fine”—this was two years or so before we met—but the police arrested him a day or two after his arrival and deported him. He can’t go back.

He’s not a refugee. But he is undocumented, sans papiers, as he has lost his ID, or rather, as he described it: “I put my carte d’identité and my passport in a mailbox. I wanted to see if they would come back to me.”

They haven’t.

He’s also sans-abri. Shelterless. Not sans-domicile. Homeless. The French make a distinction between the two.

All the numbers in this paragraph are estimates, and some are probably way off, but: according to the best sources I can find, at some point of each day most of the 2,165,423 people in Paris put there head down somewhere and try to get a bit of shuteye. Around 60,000 of these do so in commercially run residential hotels, where a small studio with kitchenette costs around 20 euros a night. These are les sans domicile, who, for various financial and social reasons, have no other options except: free state-run shelters, which only have room for 640 people a night; night shelters, which offer heat and coffee and chairs but are not equipped for sleeping; places open exceptionally in the event of extreme cold; or outside somewhere, sleeping in the rough.

Rough sleepers. This is Fred’s category, les sans abris, which the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) define as “anyone who has no covered place to protect themselves from bad weather (rain, cold) and sleeps outside (in the street, a public garden, etc.) or in a place not intended for habitation (cellar, stairwell, building site, car park, shopping centre, cave, tent, metro, station, etc.)”

According to the website of SAMU Social ( a municipal humanitarian emergency service for the homeless (Hint: Donate!), on the pre-pandemic night of January 30-31, 2020, their 2,000 volunteers counted 3,641 rough sleepers in Paris, of whom 2,664 slept in the street, 266 in metro stations, railway stations, hospitals, car parks and building lobbies, and 252 in woods, parks, gardens, and on the embankments of the Paris ring road. 426 of these were woman.

Then there are the people like Muhammed, who share illegal apartments. And the people, not so fortunate, who sleep, up to 20 to a room, in converted garages underground, the walls lined with bunkbeds, for which they pay around 40 euros each a month, and another 15 or so each for electricity etc.

“To have committed every crime but that of being a father.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

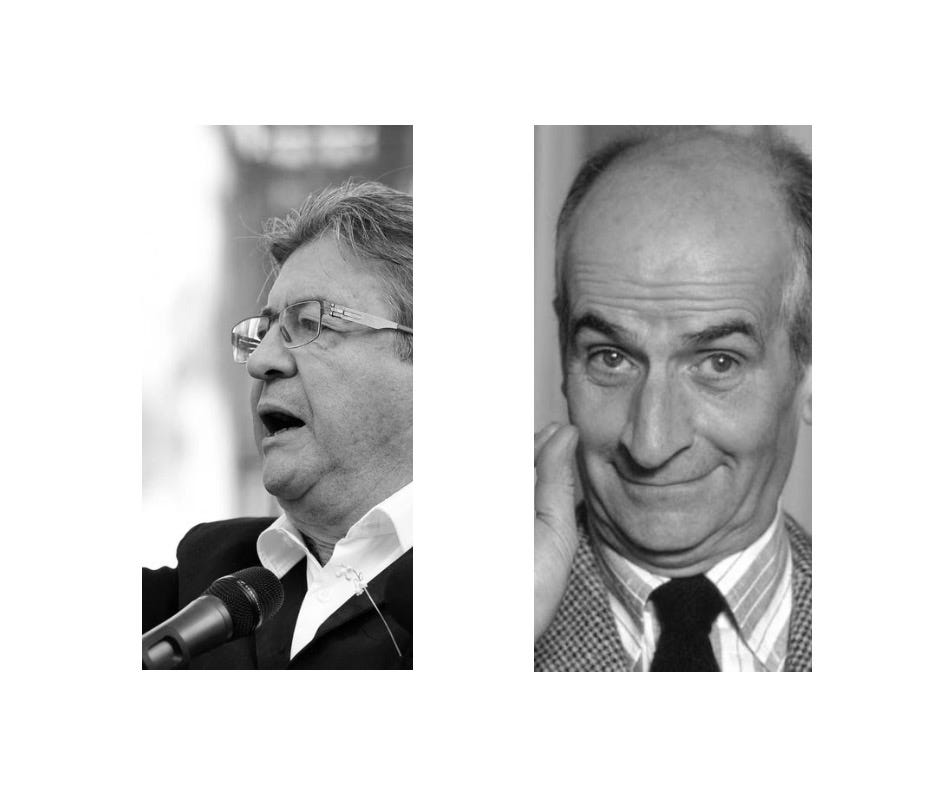

Robert is in his early eighties. He looks a bit like an older Jean-Luc Melenchon, crossed with Louis de Funès. His first wife, Fred’s mother, was half his age. No one knows where she is. His second wife was also half his age. I know this because he told me this several times. He also told me: “I am very Christian and I am sure that God will reward you, at least that is what I ask him in my prayers. May God bless you.”

I used to get blessed by a woman in front of the Franprix supermarket down the street. I don’t know where she was from or what her religion was, but she would often bless me if I gave her money or bought her food. Others less giving I saw her curse—the baleful evil eye, something muttered darkly under her breath. When they moved that Franprix around the corner, she moved somewhere else.

Anyway. How I met Robert. For about a year, during the most locked-down period of the pandemic, Fred stopped knocking on my door. When he disappeared, I assumed he was dead. Then one day he returned, wearing new clothes—expensive sneakers, a skate hoodie and shorts—and carrying a roll of crisp new 50 euro bills. He had put on weight—he wasn't overweight, he just wasn’t skin and bones anymore. His hands and fingernails were clean. His face wasn’t cut or bruised. His eyes were clear. He looked good.

“I look good, right?” he said, smiling, turning in a circle, arms up, chest puffed out. Then he handed me a piece of paper. “This is my dad’s number. Call him and tell him not to worry. I’m alright.”

Then he walked away.

“Never judge a man without putting yourself in his place.' This old proverb makes all judgement impossible, for we judge someone only because, in fact, we cannot put ourselves in his place.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

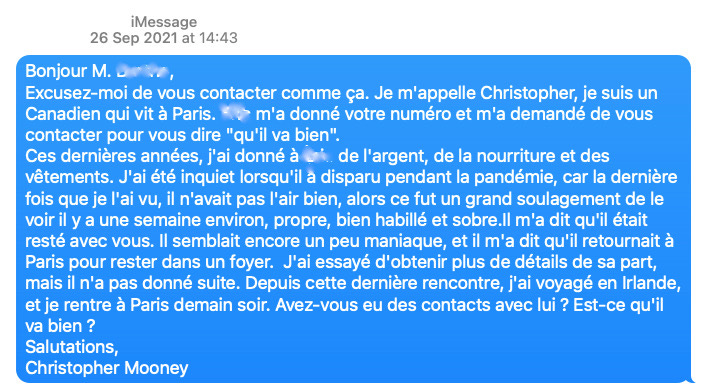

A week later I wrote a text to his dad.

Hello Mr X,

I'm sorry to contact you like this. My name is Christopher, I'm a Canadian living in Paris. Fred gave me your number and asked me to tell you that he is "fine".

For the past few years I have been giving Fred money, food and clothes. I was worried when he disappeared during the pandemic, as the last time I saw him he didn't look well, so it was a great relief to see him a week or so ago, clean, well dressed and sober. He told me that he had been staying with you. He still seemed a bit manic, and he told me he had come back to Paris to stay in a shelter. I tried to get more details from him, but he didn't provide any. Since that last meeting I have been away, and I am returning to Paris tomorrow evening. Have you had any contact with him? Is he well?

Salutations,

Christopher Mooney

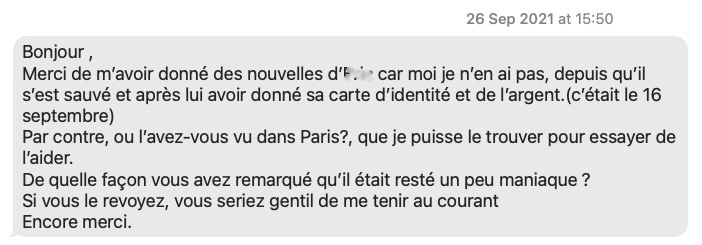

An hour later:Bonjour,

Thank you for giving me news about Fred, because I have no news since he ran away, after I gave him his identity card and some money (on September 16).

But where did you see him in Paris, so I can find him and try to help him? In what way did you notice that he was still a bit manic?

If you see him again, please let me know

Thanks again.

A few minutes later I wrote:

Ah, so he ran away. I thought so. Yes, it was the 16th that I saw him. Apparently he came by two nights ago and talked to my son while I was away. Another time he knocked on the door, but it was late and my wife was already in bed. We live near Belleville, in the 10th. I'm sure he'll be back - is there any specific message you'd like me to give him? By 'manic' I mean his gestures and the way he spoke - he was much more stable than in the past, but I felt he was heading for an episode or was about to have one. (I'm not an expert on this and I could be wrong). Is he on medication? Or is he sometimes getting treatment, or has he been prescribed treatment? I will let you know the next time I see him. I will also try to find out where he is staying.

Robert’s response:

Thank you, but where exactly did you see him? And where did he talk to your son?

What do you mean you had the impression that he was heading towards an episode?

I don't have a message for him, just to take care of himself.

Before he left he was very aggressive physically, as well as verbally.

He's let his strength go to his head... (Il a pris la grosse tête...)

When I took him in a few months ago, his face was injured in several places, he was very thin, and since then he has put on 18 kilos!

He feels strong and invulnerable and above all threatening

Thank you for answering me if you wish Me:

I never saw Fred as aggressive or threatening. He was always very gentle with us. He would get a little upset if we asked too many questions or suggested that we help him get help. The last time I saw him (before 16 September) he looked very thin and had what looked like cuts and abrasions on his face. He didn't seem to recognise me and I was very worried about him. That's why I was so happy to see him looking well the other day. You obviously nursed him back to health. He told me that he was living with his father, that his father was a great guy, but that he had to move. I got the impression that it was because of tensions with your partner.

By manic episode I mean he seemed to become somewhat disorientated - talking very fast, checking things in his pockets. In the past I had some very interesting conversations with him, in which he described himself as Spiderman, whose job was to help people. Sometimes he would show me something he had found, like a shiny stone or a coin that he thought was valuable...This, as you see from the dates, was a year ago. Since then, I’ve brought Fred and Robert together about half a dozen times. How it works: I call Robert when Fred’s at my door, we organise a meeting for two days hence. Robert drives in, and if Fred shows, which is only about half the time, we sit together on the café terrasse, Robert tries to convince Fred to come home with him, Fred says no, just give me some money, I leave, they go to lunch.

Hello Mr Christopher, I apologize for not calling you back after my visit to Paris. It is thanks to you that I was able to see my son for the third time. Everything went well. He ate at McDonald's, but he was "kicked out" because he was too dirty, plus he threw up all over the toilet..... He told me that he had eaten something bad the day before? I gave him a Covid test, it was negative. I gave him some money, I offered him to go home, he didn't want to for the moment. However, he agreed to come around January 15. The next time I come to Paris, on his request, I will offer you a small "Resto" of your choice to thank you for all that you do. Many thanks again.

The second to last time I saw Robert was in May. He brought Marie with him. The sister. She had moved back to France and was looking for a job, and looking after her father, who had cancer.

Thank you Christopher, that's very kind, as for my health problems, the doctors have discovered cancer! But I am sure that God will heal me and my wife's cancer. See you soon... I'm sorry for confiding in you so quickly and telling you about my health problems and my religious beliefs, Forget it, it's not very elegant of me. I deeply respect all people, whether they are of the same opinion as me or not. I apologize again. Kind regards.

Fred showed up, on time. He seemed excited to see his sister. But wary. They talked. Marie was very affectionate with him, but then she started getting cross.

"Just come home, Fred," she said. "Come home."

I left.

Later, she and Robert came to my door to tell me that Fred had hurt Marie when she grabbed him by the arm, and then he ran off. They were very upset.

Hello Christopher, I'm sorry I didn't dare to disturb your family! I will try to come back sooner than expected, and this time I will leave you some money and his things, if he doesn't come again. Of course if you still agree, because I understand that it can be a nuisance for you. Thanks again, see you soon. Sincerely, Robert

That was my last correspondence with Robert. We were away for most of the summer. The schizo-work friend stayed in our apartment for a few days. He gave Fred 20 euros one night. "I had to, he looked terrible," he said.

“I react like everyone else, even like those I most despise; but I make up for it by deploring every action I commit, good or bad.”

― E.M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

Last night we had a party. The Pole wasn't in his spot. Fred came by. We found four euros for him. I called Robert and handed Fred the phone. It went straight to message. I told Fred we'll try tomorrow (today). He asked for some wine. "You have a beer," I said. He wandered off. Robert called a minute later, in tears, and told me about his wife. I offered my condolences. We talked about Fred. "I can't come now," he said, still crying, inconsolable, barely able to speak. "Maybe next week... but... there's nothing I can do for him. He won't come home. The last time I found him lying in front of your house. I took him to eat. He gave me a hard time (Il m’a fait des problèmes) and demanded 200€, started getting angry and shouting very loudly in the street... It doesn't matter. He's my son and that's fine." I said I'd call him when I see Fred next. "Thank you, Christopher. God bless you. Have a nice day and see you soon."

I hung up, went back to the party.

A few minutes later, Muhammed showed up with his bouquet, singing and smiling.

I can’t thank you enough for your wonderful writing. Subscribing to Hexagon is one of the wisest decisions I’ve made this year.

This is a moving piece.