Pyre or pyre

"Quand on veut que tout change, on appelle le feu." – Gaston Bachelard, La psychanalyse du feu, 1938

1.

On Tuesday, when Gary Indiana’s library came to Los Angeles, it rested for a while in the appointed house in Altadena. But it was the wrong day. If they – the signed editions, the rare art books, the weird books, the books Gary treasured – had come a day later, there would have been no address to deliver them to, so they would have been saved. But on that Tuesday, unfortunately, there still was an address. – Colm Tóibín, “In LA”, London Review of Books, 23 January 2025

As Lucretius tells us, the air we breathe is made of single atoms (and molecular compounds, which Lucretius had not considered) in constant motion and of no fixed address. Called ‘gasses’, from the Latin word chaos, which means ‘empty space’ or ‘void’, they have neither shape nor volume. They randomly collide into each other, banging off the surfaces that enclose them while ever expanding, until whatever vessel they find themselves in is filled to its brim. Mixed in with these phases of matter – nitrogen, oxygen, water vapour, argon, carbon dioxide, neon, helium, krypton, hydrogen, and methane – are clouds and hazes of suspended particles or droplets.

Air, then, is a substance, a particular instance of material, and substance, a general concept or idea of matter, in the Aristotelian sense, like a person or a tree. Or this text. It exists in itself and not in another. It persists through change. It fills the emptiness and is the emptiness. For Lucretius, air, like all natural substances, operates according to natural laws without divine intervention. This is still true, even truer, for to our fallible eyes and narrow ken – and the machines we build to transcend their limitations – air is distinct and consistent but also unpredictable. It only enters our consciousness – becomes perceivable, phenomenal – when the particulates and aerosols in its clouds and hazes become too top-heavy with dust, pollen or soot, or volatile chemicals from paints, cleaning supplies, pesticides, building materials, and personal care products, or when its baser compounds include high concentrations of ozone, carbon monoxide, chlorine, sulfur dioxide, or nitrogen dioxide. Under these too-common conditions, air becomes an aberration we smell and taste. It makes our eyes itch and our throats sore and our deaths soar – by the millions, every year.

Wind, on the other hand, is substance but not a substance. It is a phenomenon – an event – made manifest to our senses and interpretable by our minds when changes in air pressure force air to move horizontally. This is observable and experiential; we register its presence; we feel it; we hear it. We write poetry about it, some of it good, most of it terrible. Sometimes, depending on our mood or the state of our mind, it reminds us, at a baseline level of consciousness, that all forces of nature are subject to the same laws of physics, and even the most seemingly random occurrences have an explanation, a reason, a cause.

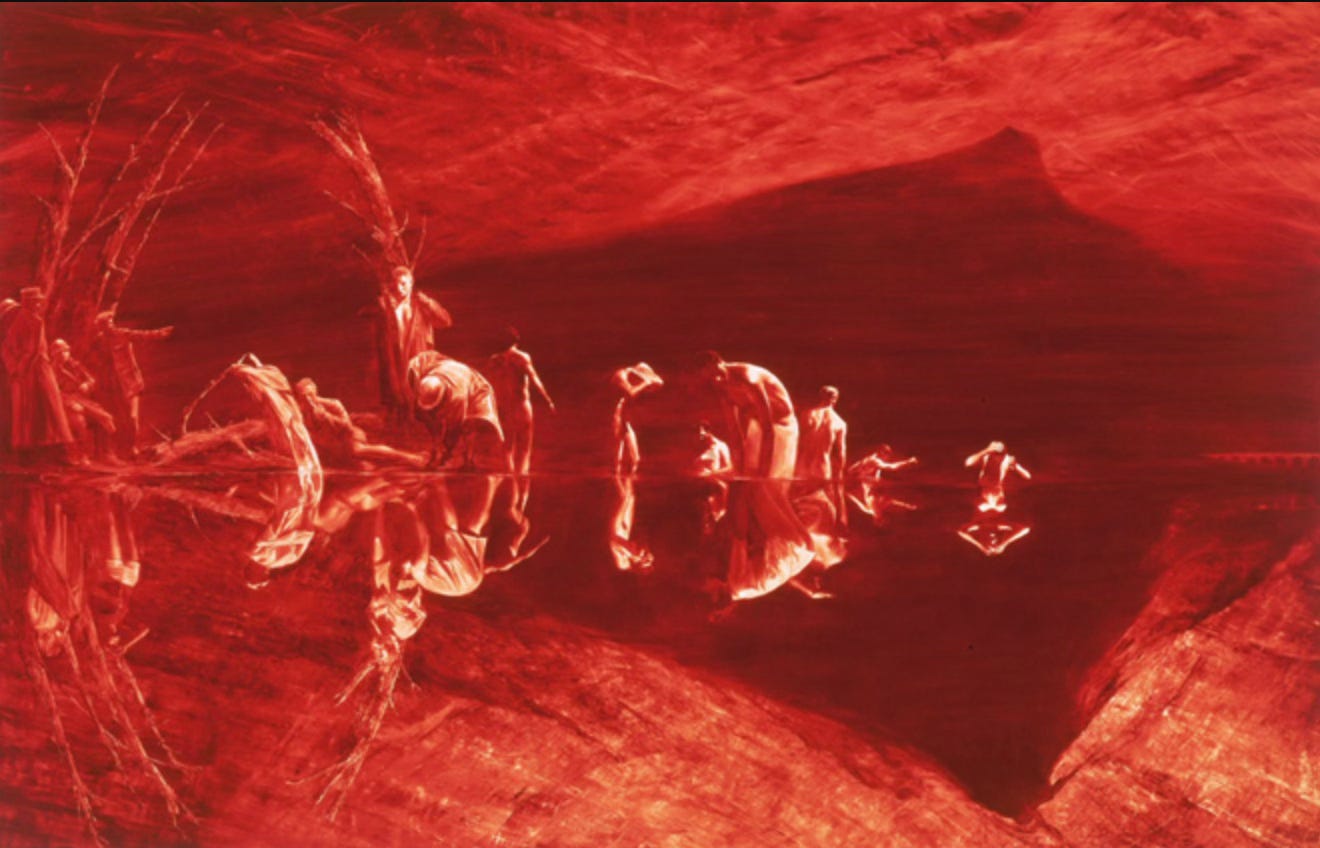

Fire is different. Fire is substance and phenomenon. Through it, matter is transformed into energy in the form of heat and light. Controlled or not, these properties draw us to it, just as they have since the first spark, since the so-called dawn. It warms, it burns, it bewitches and terrifies. We have learned to love it and fear it and never recklessly speak its name – we are wary even to name it – for one’s tongue is also a fire, which discharges sin and error. A careless or wrongly placed word from it can ruin the world, turn harmony to havoc, set the whole course of one’s life on fire, and is itself set on fire by hell.

2.

Birds like pine cones explode from the trees. Many caught inside the blaze

insist it has lungs (they can hear it breathing),

a belly that's never full, a quickness of the brain

- Lorna Crozier, “The Gods Don’t Tell Us Everything”, CBC Radio, 14 July 2017

All but two of the more than two dozen works by the great Egyptian scholar and visier Jamāl al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan 'Alī ibn Yūsuf ibn Ibrāhīm ibn 'Abd al-Wahid al-Shaybānī (جمال الدين أبو الحسن علي بن يوسف بن ٳبراهي بن عبد الواحد الشيباني), better known as 'al-QifṭīIbn al Qifti or, simply, Al-Qifti, were destroyed by fire during the Mongol Invasion. The only surviving titles are the Kitab Ikhbar al-'ulama' Akhbar hakama, more commonly referred to as Ta'rikh al-hukama (“The History of Learned Men”), a biographical dictionary of 414 Arab physicians, philosophers and astronomers written in 1249, and the three-volume Inbah al-ruwat 'ala anbah al-nuhat ("Informing the Narrators about the News of the Grammarians"), purportedly written that same year and containing almost a thousand biographies of Arab scholars, linguists, and philologists. Early editions of both are in the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Library of Congress, the Vatican Library and the National Library of Egypt. All are considered incomplete and corrupt.

Our current focus is on a controversial passage in Tarih al-Hukama that discusses the destruction of the Library of Alexandria by Arab invaders in the seventh century. The story begins with Yaḥyā al-Naḥwī, a bishop in the church of Alexandria who, after a period of intense philosophical study, could no longer believe that the One had become Three and that the Three could be One. When the bishops of Egypt discovered that he had rejected the Trinity and, with it, his faith, they were furious, and he was dismissed.

Yaḥyā lived through the conquest of Egypt by Amr ibn al-ʿĀṣ, who knew his scholarly reputation and position on the Trinity and the conflicts it caused him with the Christians. He listened to Yaḥyā's discourse on the impossibility of the Trinity and found it pleasing, and he was equally amazed by Yaḥyā's discussion on the cessation of the world, despite the logical proofs presented. Being sensible, a good listener, and a deep thinker, Amr welcomed Yaḥyā into his company and did not wish to part from him.

One day, Yaḥyā asked Amr for the books of wisdom in the royal stores, which were now under Amr's control but of no use to him. Amr asked about their origin and significance. Yaḥyā explained that the pharaoh Ptolemy Philadelphus, who valued science above all, had tasked a learned man named Zamira with collecting them, resulting in a library of 54,120 books. The Pharaoh then asked Zamira if any books were missing. Zamira confirmed many still existed in places like India and Persia, and in Armenia and Babylonia and Mosul and among the Byzantines. Pleased, the Pharaoh continued the collection, sometimes by violent means, until his death. Subsequent Alexandrian governors kept the collection intact for the enlightenment and pleasure of the pharaohs and their successors.

Amr ibn al-ʿĀṣ, impressed, wished to have the books, but knew he must first seek the blessing of the Prince of the Believers, Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb. Umar told him that if the books complied with the Qur'an, they were redundant, and if not, they should be destroyed. Consequently, Amr ordered the books to be burned to heat the public baths, reportedly providing fuel and blackening the skies of Alexandria with smoke for six months, an event that left many in awe.

Most contemporary scholars reject this account, principally because it is now believed that Yaḥyā died of gout years before the conquest of Egypt even began.

3.

All eyes were raised to the top of the church. What they saw was extraordinary. On the top of the highest gallery, higher than the central rose window, a large flame rose between the two towers with swirls of sparks, a large, disordered and furious flame, a tongue of which the wind occasionally flicked into the smoke. Below that flame, below the gloomy balustrade’s ember-lit trefoils, two spouts with monstrous mouths vomited forth a burning rain… Above the flame, the enormous towers, each with two stark and sharply contrasting faces – one entirely black, the other deep red – seemed even larger because of the vast darkness they cast into the sky. The countless sculptures of devils and dragons took on a mournful appearance. The flickering light of the flame made them appear to move. There were wyverns that seemed to laugh, gargoyles that one would swear were barking, salamanders blowing into the fire, and tarasques sneezing in the smoke. – Victor Hugo, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1831

I met a man from Korea yesterday. I was with my youngest daughter, we were having lunch on rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, he was seated at the next table and, like us, eating the house speciality, lamb durum, and drinking ayran from a shiny metal cup. In near-perfect French, he told us that he worked for a producer of sulfur dioxide (SO2) scrubbers for power plants and was in France to promote a new generation of flue gas desulfurisation systems. Or, rather, he told me – my daughter had her earbuds in, out of which throbbed the stripped-to-tin, far-off-in-the-distance beats of a Freeze Corleone rap song.

The Korean man said his name was Chin or Jin, let’s use Chin, and that this was his first trip to Paris. When I asked what he had seen so far, he lowered his head, closed his eyes, and made the sign of the cross.

‘I am a Catholic,’ he said, ‘Sort of, an offshoot. My parents raised me as a shamanist, but we converted when I was a teenager. I was baptised in a community centre. I attend mass in a Burger King.’

He saw my expression. ‘In Incheon. It’s a secret mass.’

4.

The dove descending breaks the air/ With flame of incandescent terror / Of which the tongues declare / The one discharge from sin and error. / The only hope, or else despair/ Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre- / To be redeemed from fire by fire. – T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding”, 1942

Surprisingly, despite the wildfires in Los Angeles, the air quality was much better than in Paris this month.

Los Angeles County maintained moderate air quality, with Air Quality Index (AQI) values ranging from 28 to 60. Greater Paris experienced higher pollution levels, with AQI values ranging from 42 to 92, indicating moderate to unhealthy air quality.

The AQI focuses on common pollution sources like car exhaust and smog. It measures five major air pollutants: ground-level ozone, particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide. The AQI scale ranges from 0 to 500, with higher values indicating worse air quality and greater potential health concerns.

The AQI, however, doesn't account for many harmful gases or particles produced by burning structures, such as synthetic roofing, furniture, and appliances, which can release carcinogens like benzene, formaldehyde, asbestos fibres, or metals.

At the peak of the wildfires, the New York Times reported that early measurements indicated that lead levels in the air surged to 100 times their normal concentration, even miles away from the fires. Chlorine levels, also hazardous in small amounts, increased to 40 times the average.

The Notre Dame de Paris fire in April 2019 caused significant lead contamination in the surrounding areas. The cathedral's roof and spire, which contained about 400 tonnes of lead, collapsed during the fire, releasing lead particles into the air. This lead dust spread across Paris, raising concerns about potential health risks, especially for children. Earlier this month, lead concentration levels ten times higher than the alert threshold were measured in schoolyards and classrooms near the cathedral.

5.

Sans aucun stress, sip un verre de danger (lin, lin, lin, lin) / J'fume que d'la frappe comme le maire de Tanger / Bellek, j'suis dans l'complot comme le maire de Angers / Comme Kodak, capture le moment, fils / C'est comment, fils ? / J'viens prendre les commandes, fils… – Freeze Corleone, “Intro: Track One”, Projet Blue Beam, 2018

Chin told me he had never been to a cathedral. He asked if I would take him to Notre Dame, and I said, ‘Of course, I would be delighted to’. Which, of course, wasn’t true. The cathedral had just reopened after the fire. The crowds, I was sure, would be intolerable. I told him this; he nodded, then explained that he had no desire to enter the cathedral, only to stand in front of it. ‘I have already prayed to my Lord on this trip. I just need to see the facade.’

Chin’s prayer had taken place during a visit to a power station in Gardanne, a village in Provence where Cezanne had lived for a year. Ten years ago, the plant was retrofitted, at great expense – more than 300 million euros at the outset, a further 500 million euros since - into a recycled wood-burning power station, but it had been barely used since because of rising biomass costs, the termination of its contract with the state, and years of bitter strikes and social conflict – most people in the region didn’t want to switch from coal to biomass. They wanted steady employment.

‘I prayed there,’ Chin told us (the Freeze Corleone song had by now ended; my daughter had removed the earbuds). The power station’s chimney is almost 300 metres tall,” he said. ‘Twice as tall as the tallest in Korea. I kneeled before this chimney. I asked my Lord to intervene, to guide my steps and walk with me, to shed His light where I have been, and help my clients’ hearts to truly see.’

Understandably, I found this puzzling, and upon hearing it, I began to wonder about Chin’s mental state. I didn’t say anything, but I think he saw something on my face.

I asked him if he had seen any of Cézanne’s many paintings of Gardanne.

He said he had not.

6.

Henceforth, how can painters be Christians?… ‘Imagine that the history of the world dates from the day when two atoms met, when two whirlwinds, two chemicals joined together.’ — ‘… this dawn of ourselves above nothingness, I can see them rising, I immerse myself in them when I read Lucretius.’ … Cézanne read lots of Lucretius… [whose] interest concerns atoms, of course, the dance of atoms, but equally strangely, it concerns colours and light. – Gilles Deleuze, Seminar on Painting and the Question of Concepts, March 31, 1981

Paul and Hortense Cezanne and their 13-year-old son Paul lived in a rented apartment on Cours Forbin in the centre of Gardenne from the summer of 1885 to the spring of 1886. It is not clear why. Perhaps it was simply because it was further inland from the sea, which the Impressionists had by then painted to death, or because Gardanne was built on a hill, with a chapel at its summit, like an Italian village in a Poussin background. Cezanne’s guiding ambitions at this time was “faire du Poussin sur nature” and “refaire Poussin d’après nature”, by which I think he meant create imaginative fictions that were composed classically but also faithful renderings of the natural world – the real world – based on direct observation. But I could be wrong.

The Cezannes had lived together for 12 years and had only married two months before moving to Gardanne. They enrolled their son at the local school. At the time, the village had about 2500 inhabitants, mainly farmers, tenant farmers, day labourers and their families. Earlier, the farms around town grew saffron, bedstraw, and tobacco, but wheat, oats, barley, and sugar beets were replacing these. As was manufacturing and industry. There was already a coal mine, employing 282 workers, and a pottery, two tile factories, and a lime factory. The village’s buildings and vegetation were not yet coated with ochre-coloured dust from Gardanne’s bauxite-to-aluminum plant. Nor had millions and millions of tonnes of red toxic mud flowed from its effluent pipes into the Rhone estuary and calanques. The bauxite plant, now the oldest in the world, didn’t open till 1893, by which time the Cezannes were back in Aix, and the painter had refocussed his attentions on Montaigne Sainte-Victoire.

7.

“Look at this Sainte-Victoire. What momentum, what an imperious thirst for the sun, and what melancholy in the evening, when all this heaviness falls... These blocks were fire. There is still fire in them. The shadow, during the day, seems to recoil shivering, as if afraid of them; up there is Plato's cave: notice when great clouds pass by, the shadow that falls from them trembles on the rocks, as if burned, immediately swallowed by a mouth of fire.” – Paul Cezanne, in conversation with Joachim Gasquet, 1898 or 1899.

‘I am not interested in painting,’ Chin said. ‘I prefer statues.’ This was why he wanted to see Notre Dame, to see the gargoyles and salamanders on its edifice, and especially the wyverns and tarasques mentioned in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, which Chin has read four times.

Chin desperately wanted to see a Tarasque, a dragon that was ‘part animal, part fish, thicker than an ox, longer than a horse, with teeth like swords and as large as horns.’ He had first read an account of it in The Life of St. Mary Magdalene and her sister St. Martha (Vita Beatae Mariae Magdalenae et sororis ejus Sanctae Marthae):

A horrifying dragon of unbelievable length and mass, spewing pestilent fumes with its breath and sulfurous sparks from its eyes. It emitted hissing sounds from its mouth and roared horribly with its hooked teeth. With its talons and teeth, it tore apart anything it encountered, killing anything that came close with the deadly stench of its breath.

Originally misattributed to the 9th-century Benedictine Raban Maur (d. 856 AD), The Life of St. Mary Magdalene and her sister St. Martha is now believed to have been written by an unknown “pseudo-Raban” author sometime between the late 12th century and the second half of the 13th century.

The largest Tarasque ever recorded lived about 100 kilometers west of Gardanne. One day, it swam up the river and entered the village of Nerluc, wreaking havoc and devouring the inhabitants. Despite the villagers' pleas, the French king refused to help, and the Tarasque attacked for many weeks. Finally, aided by wizards and witches, St. Martha tamed the beast with a song, and poured holy water down its throat to extinguish its fiery breath. She led the beast into town with a leash made of her hair. The villagers killed it with swords and stones. The beast's reign of terror came to an end. The village of Nerluc was renamed Tarascon to commemorate the Tarasque's death, and an annual festival is held to reenact its defeat.

8.

Think of the earth’s history as dating from when two atoms met, when two whirlwinds and chemical dances joined together. When I read Lucretius, I drench myself with those first huge rainbows, those cosmic prisms, that dawn of mankind rising over the void. In their fine mist, I breathe in the newborn world. I become sharply, overwhelmingly aware of colour gradations. I feel as if all the shades of the infinite saturate me. At that moment, I and my painting are one. Together, we form a blue of iridescent hues. I come face to face with my motif; I lose myself in it. My thoughts wander hazily. The sun penetrates my skin dully, like a distant friend, warming, fertilising my laziness, and together we germinate. – Cezanne, in conversation with Joachim Gasquet, 1898 or 1899,

In the intro track to Projet Blue Beam, Freeze Corleone references Christophe Béchu, the current French Minister of the Environment, who has taken flack for his use of private jets for official travel, for his “shamefully” (Le Monde, Ouest-France) underwhelming response to climate issues and complete lack of real ecological planning to successfully carry out what his boss, the French President, calls the "fight of the century", with the line: “Bellek, j'suis dans l'complot comme le maire de Angers” (Béchu is the mayor of Angers). Corleone alludes to Béchu's attendance at the 2012 Bilderberg Group meetings, which fuel various conspiracy theories, including a colourful Canadian one called Projet Blue Beam. Proposed by Quebecois journalist Serge Monast in the 1990s, the theory claims global elites plan to create a “New World Order” using advanced holographic technology to simulate religious and extraterrestrial events. The goal is to manipulate and control the population through mass hysteria and uncertainty. Monast said the project will unfold in four stages:

Re-evaluation of Archaeological Knowledge: Artificially induced natural disasters would lead to new ‘discoveries’ that challenge existing religious beliefs.

Space Show: Holograms of religious figures or extraterrestrials would be projected worldwide, speaking different languages to promote a single global religion and ideology.

False Alien Invasion: Simulated alien invasions would create fear and chaos, leading people to seek protection from the authorities.

False Savior: A fake second coming of Christ or other divine figure would be projected, leading to the establishment of a global dictatorship.

No credible evidence supports this theory, and it remains widely debunked.