I have hardly anything in common with myself and should sit in a corner in silence, content that I can breathe. —Franz Kafka

Later, settled into a different armchair, unsure what had just happened, the blood pooling in his head imperceptible to the frenzy of guests eating his food and drinking his wine, his focus returns to the hazy figure of his mistress as she makes her way through the crowded room, charming the men by rebuking them and ruffling the feathers of their tight-laced wives. He imagines the looks she gives, the bewitching flash in her grey-green eyes as she steers to a new prey, leaving the last one silenced and flushed. Leocadia Weiss is rarely the most beautiful woman in a room, but almost always the most attractive. What is she saying? She bends down to him, close enough for him to see her frown, and stares into his eyes. Then she writes something in the Conversation Book, which is on his lap, and disappears into the unfocussed mass.

He can’t find his reading glass, can’t read what she has written.

When he was younger, he often complained about the people he loved. Who, he was sure, loved him just as much in return, but who refused him their favours. After all these years with Leocadia, he understands this better, but this doesn’t decrease his frustration. Desire, to live, must be denied, and love, in all its forms, is like a pheasant disappearing in the brush.

His thoughts aren’t clear. His head is pounding.

Why has he never been able to paint Leocadia’s likeness? Why couldn’t he paint his wife’s? He must change his will. Or has he done this already? Leocadia and Mariquita. Juana, too, his maid. His assistant. He will speak today with Galos the banker about the terms. Javier, his son, will make a fuss, but there is more than enough money and property for everyone. At Javier’s age, he had nothing. He paid for his father’s funeral, paid the family debts, supported his siblings and his nieces, and, at his wife’s insistence, took in his half-scrambled old mother, who shared a room with Javier, filling the poor boy’s head with stories of witches and brujos until she was finally moved to his brother Camilo’s house in Chinchón. Which he also paid for.

And then, he remembers, it was not just Cabarrús’s remains that Brugada had told him about. All at once the rest of the tale comes to him, so focussed had he been that day on trying to walk without Brugada’s support, his feet ablaze with pain from gout—halfway to the shop he bellowed at the young man, who was signing the story with one hand, as the other was occupied with Goya’s shifting, unstable heft, “Can't you make your gestures more discreetly? Do you take pleasure in allowing everyone to see that old Goya is neither able to walk nor to hear?”

He had completely forgotten the other horrific part: the fate of Floridablanca, the disgraced chief minister who first introduced Goya to the court and gave him his first commissions. Floridablanca’s corpse, which had been interred in the next pantheon to Cabarrús in the Cathedral of Seville (he died in 1808, Cabarrús in 1810), was exhumed by the feral king’s henchmen and tossed into the common grave in the Caliphate courtyard of ablutions, where executed criminals were buried. Floridablanca! Who freed the universities and the press and expelled the Jesuits. Who brought gaslights to the streets of Madrid. Who gave his life and his freedom to his country. Who embraced all things liberal, and then, when necessary, when the calamitous events in France required, abandoned and vigorously repressed them.

Where are his portraits of them now, old Goya wonders, old Cabarrús and Floridablanca. Painted so long ago, before the revolutions and the bloodshed, before his deafness and his plagues. Full-length both and among his best, what sad fate had befallen them? Should he ask? Ask who?

Leocadia and Mariquita are in front of him, close enough that he can almost read their lips. Realizing, he is sure of this, they turn away. What is being said about him? Why are all these people here?

Ask who? He has no friends in the present Council and his sworn enemies still thrive. They hold positions backed by absolute power and lie in wait to strike.

He hid from the mob in the priest Duaso’s house four years ago, painting portraits for his room and board before the amnesty allowed him to flee to France. Since, nothing. Twice welcomed home to Madrid, the court generous, his retirement accepted, his pension guaranteed. His portrait by López in the front hall of the new Royal Museum. But there are enemies everywhere and spies everywhere. And who would he ask, anyway? Ghosts know only the past and the future, never the present. This is their only recompense.

Dante learned this from his sworn enemy, Munárriz told him this story, of Farinati, who died in exile and whose corpse the Inquisition dug up two decades later, tried for heresy and burned to ash, along with his dead wife, for publicly celebrating the pleasures of the flesh, for telling all who would listen that they should sup on only the best and most delicate viands, not on dry crusts of bread, and eat without waiting to be hungry, because nothing lasts, and the soul dies the same death as the body.

When the Poet meets this embittered wraith proven wrong, sweltering for all eternity in its fiery coffin in the sixth circle of hell, it spits at its fate and its punishers; and, knowing what the future holds, tells Dante of his own imminent exile: "But the face of Hecate, who reigns in Hell, shall not be 50 times rekindled in its course before you learn what griefs attend that art.”

Mariquita returns with his glasses, helps him perch them on his nose. She opens the Conversation Book. He peers at Leocadia’s last entry: “I will explain that you are tired and that it is time to move the party to Braulio’s shop. Juana will take you to bed.”

He squeezes Mariquita’s hand. She stares at him blankly. Eighty-two and still nothing, still stupid. Why was he not wise? His daughter was lost, he couldn’t see anything but he could see this, and he had nothing to tell her. Not even that she was his daughter.

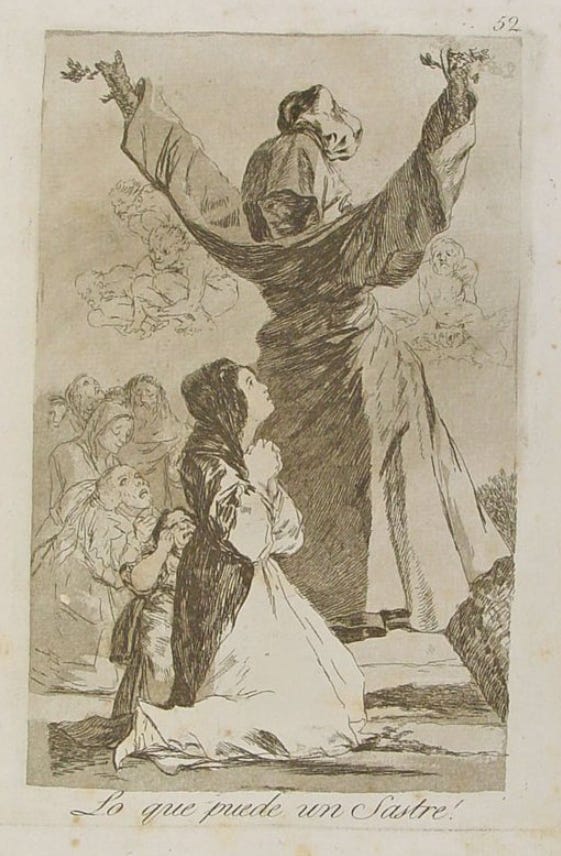

She who reigns in Hell is Hecate the moon goddess. The mother of angels, the protector of boundaries. Goya painted her for the Duchess of Osuna’s bedchamber 40 years ago, naked but for a leaf crown, a torch in one hand, a viper in the other. “Hecate,” he wrote under the image, as though it were an ex-voto offering from the New World, “the far-reaching one, the source of hag and hex, served by eunuchs and revered by witches.”

On the last night of each month, the night of the new moon, Hecate feeds the spirits of the unavenged, the erroneously executed and the wrongly sacrificed, accompanied by the ravenous dogs of the underworld. He painted her thus, too, for Manuel Garcia de la Prada, in the same batch as his La casa de locos, Escena inquisitorial, Procesión de disciplinantes and the grotesque El entierro de la sardina, with the restless dead and the dogs, but larger and more rapidly, not with more assurance but as if in a fever—X-rays show no pentimenti—with thin layers of black over an orange-rust ground, and tiny drops of white over long swift strokes with a palette knife for her gossamer gown.

Juana will bend down to him soon, help him up with her strong arms.

When Floridablanca and Cabarrús were still in office he did Hecate’s triple-bodied form, the Hekataion, for Jovellanos, standing guard at the shadowed crossroads at nightfall, torches, keys, daggers, and serpents in her six raised hands, watching over the dismembered dead hanging on posts under a portentous sky filled with bats and owls, surrounded by evil-eyed lynxes and snarling hounds of hell. In another, she has the faces of a dog, a polecat and a boar. She is a lasting obsession. Farinati, in his burning tomb: “But the face of Hecate who reigns in Hell shall not be 50 times rekindled in its course before you learn what griefs attend that art.” Goya ponders this anew. Forty-nine lunar revolutions. Forty-nine new moons. Four years and one month. The precise length of Goya’s exile, which will end, as has just been decreed, in 18 days, with his death.

Upcoming

EODJ (aka Soaking Wet February) Cave à Michel, Paris Thursday, February 1, 2024 (20:00-24:00) Hexagon (TBD) Sunday, February 4, 2024 Holdback Episode 3 Sunday, February 10, 2024 "The Hidden Vineyards of Paris" book launch with Geoffrey Finch & Paris Wine Walks The Red Wheelbarrow, Paris Thursday, February 29, 2024 (tba)