“Thought” of the day: I am bemused by “bemused.” I don’t think it should mean what it means. Further, if it does mean what it means – confused – and “amused” means beguiled, shouldn’t “cemused” exist and mean… something that begins with “d” like… deluded?

Demused. Emused. Femused. Gemused. Hemused. Which calls to mind page 689 of Ulysses.

Sorry. I’m slightly out of sorts as I’m four weeks into my Breton farm retreat and nowhere near finishing the writing goal I assigned myself.

An opera. About the writer Raymond Roussel. In French.

Excuses? Editing and writing assignments have got in the way, and these Hexagons take their weekly toll. Plus, there are the sheep and the goat to feed, and the lawns to cut, not to mention coastlines to explore, beaches to swim, forest trails to run, oysters to shuck, crêpes de blé noir to eat, and ridiculously delicious cider to drink.

Nothing to complain about, right? And I’m not so brazen as to use this to beg you for financial support – even if that support costs less than a single Breton buckwheat crêpe a month. No. Never.

Besides, I’ve made considerable headway. Scenes are taking shape and are funnier and weirder than I expected. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. Roussell was bemusingly colourful. He thought fame – "La Gloire” – shone directly out of his forehead onto the typewritten page. He thus worked in the dark, with the curtains drawn, because his writing was “so powerful that the light from it would blind the world.”

He visited every continent except Antarctica but stayed at his typewriter almost the entire time, rarely venturing out because he “didn’t want life to get in the way of my imagination.”

Imagination he had. A play of his based on his novel Impressions d’Afrique had scenes in which an earthworm played the zither, an imaginary substance called bexium powered a “thermomechanical" orchestra, a one-legged flute player played a flute made out of his own tibia, and a statue of a Spartan slave made of whalebone corset stays rolled across the stage on rails made of veal lungs. (I’ve found a spot for the whalebone corset Spartan slave and the veal lung railway tracks, and I’m working on the others.)

He never wore a shirt, socks, cuffs, or underwear more than once. He ate one meal a day, five hours long, 20-35 haute-bourgeoise courses.

He saw Tristan and Isolde a hundred nights in a row. Always in the same seat. Accompanied by a woman his mother paid to pretend to be his mistress.

His mother was just as bemusing: she had a window put into her coffin – just in case, and always travelled with it, even on a voyage to India, which she had always wanted to see and which ended when her yacht reached sight of its coast and she said, “there, it is” and had the captain turn the boat around and sail home.

Anyway, the libretto is coming together, piece by piece. I think I have entire structure figured out. I can see it in my head. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen, heard, or thought about. And I have a week left.

In the meantime, here’s our old friend Goya, who we haven’t heard from in two months.

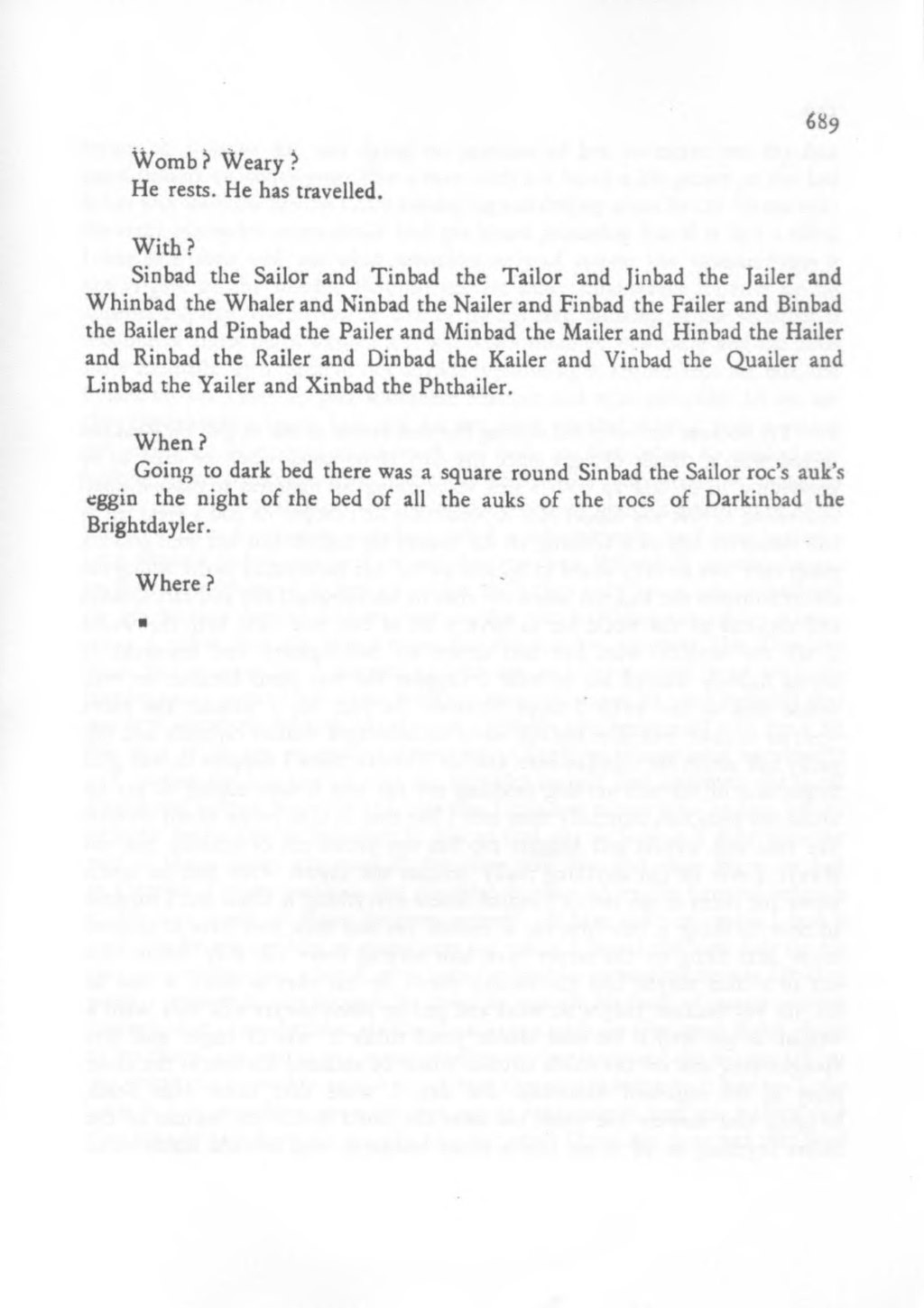

This is the second plate in Los Caprichos. Goya’s smirking self-portrait, which precedes it, was an afterthought, a replacement for the more dangerous image of the man slumped in the chair succumbed to the sleep of reason. Is this image not as dangerous? It depends on how we interpret it.

A young woman climbs a darkened flight of stairs. A mask of a dog’s face covers her eyes. A rat’s face or a dog’s, worn like a bridal comb, covers the back of her head.

A woman pretending to be an animal. Getting hitched.

¿Qué carajo?

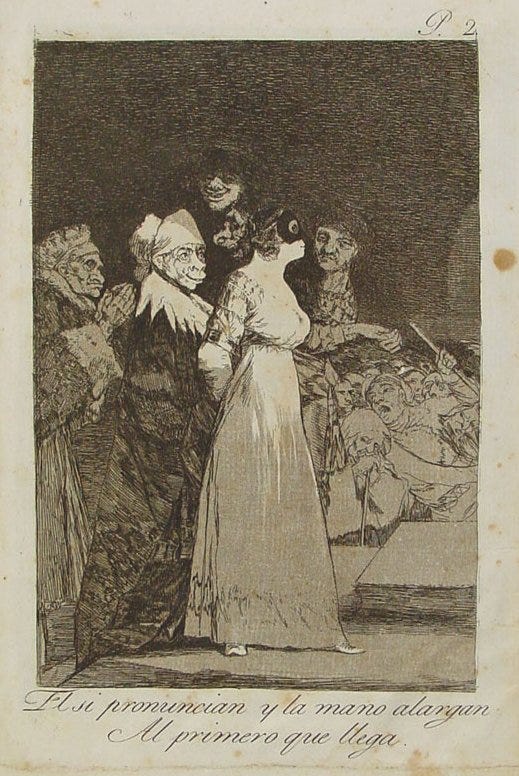

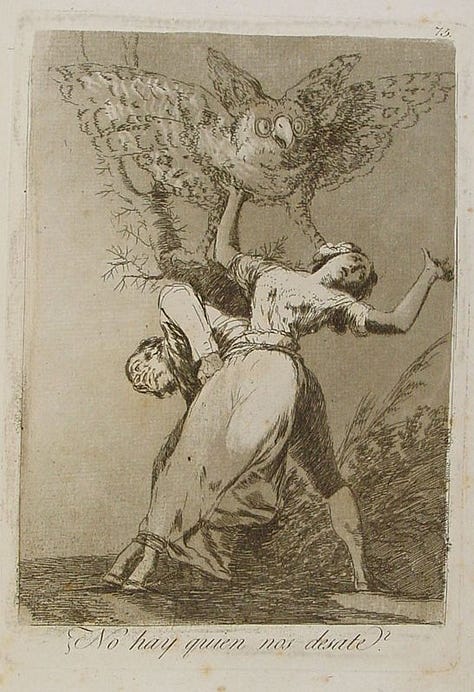

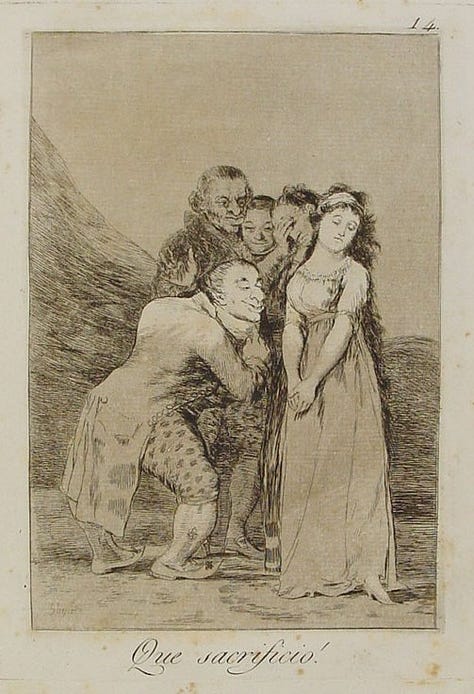

Other Caprichos treat similar themes:

Goya here is quoting a Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos’ poem from a play about marriage, and this is why we are climbing the steps with the pretty young bride and her decrepit groom, up out of the shadows and the jeering mob toward the dark altar at the back of a half-lit cave, a grottoed church whose only light comes from below, not from torches but from hell itself, the ever-replicating hell of his most hellish images.

How many, oh Alcinda, yoked to marriage, Envy your fate! How many seek the yoke of Hymen To secure their fortune, And without using reason nor considering The merits of their suitor, Say yes and extend their hand To the first who arrives! What evils This cursed blindness brings! I see the wedding torches extinguished By Discord's infamous breath At the foot of the altar, and in the chaos Toasts and cheers of the wedding feast, An indiscreet tear predicts Wars and disgrace for the poorly united. I see the marriage veil torn by a reckless hand, And with imprudent head held high, Adultery runs from one house to another.

“The ease with which many women agree to marry, hoping to live with more freedom.” This is the caption in the Prado manuscript, probably written by Goya and worded to mask the work's riskier meanings. Elsewhere, he wrote: “Art, like love, to be faithful to truth, must have no expectations, except to be free.” The Bibliothèque Nationale's edition is more scathing: “Marriages are regularly made blindly: brides, trained by their parents, mask themselves and dress up nicely to deceive the firstcomer. This one is a princess with a mask who will later be a bitch to her vassals, as indicated by the back of her head imitating a comb: the foolish dupes applaud these unions, and behind comes a liar in priestly garb praying for the happiness of the nation.” No one knows who wrote this. Nor this, below:

“Her parents are with her. They seek to disburden themselves of this daughter and have thus trained her to say yes to the first man who comes along, in this case, the impotent old goat behind her, to whom she has eagerly given her hand, for her desire to escape her parents’ suffocating discipline easily outweighs her repugnance, as is made clear by the way she has furtively thrust her fingers inside the folds of his gown, where they are fruitlessly engaged in resuscitating his lolling untumescence.”

Her frowning father clutches the other hand, and up the gallows stairs they go, past the seething mob, out of which a man's grotesque head and torso emerge like a breaching whale, his clouting stick raised to strike. Higher still is the head of another predator, a grinning giant with a bearish snout who licks his lips and eyes the young bride lasciviously. Two toothless Januses look back at him nervously, down at the braying mob, and forward at the altar. Behind them, a pretend priest, hands clasped, pretends to pray.

The parents behind are pleased with the arrangement. The mother is devoted to excess and frivolity. She has neglected the girl's Christian education. She has replaced her mantilla and basquiña with an Empire gown. She has taught her to speak French and dance and have elegant manners.

But what precisely drives these two towards the wedding bed? A unity of will? Lust? Greed? Is the deception mutual? And who is the old crone bent over her cane? Or is the young bride the witch? The masks betray hypocrisy but also cunning. She bends to survive the winds and the wages of sin in a sinful world. Everyone sees this except the seething sea of witnesses below.

“Here, as everywhere else, the most beautiful have always the first chance of success. Most obtain several dowries at once. These objects of monastic favour are often the concubines of amorous priests. Each girl, at the approach of a certain critical period, is provided with a husband who only takes her for the sake of the money. What was once the father's property becomes the husband's property.”

Who wrote that?

Who also wrote: “There was a time once when a sense of shame gilded their crimes and covered timidly the ugliness of vice.”

He does not regard marriage as the sole union between the sexes where desire does not degrade its participants or violate moral law. He believes that in a union, each has the right to control and use the other, body and soul. He believes that true human love is genuinely blind, making no distinctions. However, isn't this, too, merely appetite, where people are things to use? Where is the goodwill, affection, the pursuit of shared joy, the delight in another's happiness? If there is only desire, everything else is forsaken. Desire, in its quest for satisfaction, is indifferent to the misery it may cause. It cares only for its fulfilment, discarding everything once sated, like the bones of a carcass. Only in friendship between equals is there true restoration.

Love draws us too close; respect keeps us a proper distance apart. Our friends are flawed, just as we are, but we learn to accept those flaws. Our dignity remains intact, as does our trustworthiness, honesty, and conscientiousness. Martin was right never to marry. Even when it works well, like his once did, the two fused into one, it is a hideous folly, the most terrible addiction of the human race.

We are animals, he thinks. Animals pretending not to be animals. Sometimes, we have to be reminded of this. Sometimes, we have to return – or be returned – to our truth.

He remembers a scene in Younger Moratín's play with Mariano Querol, who died before paying for his portrait, playing the servant Munioz hiding under the sofa to eavesdrop to the young married couple's conversation.

What does he hear? He can't remember. He still had his hearing then, but he can't remember.

When? He thinks of how, just yesterday, sitting outside in the sun, he moved behind Leocadia so that she blocked the sun from his eyes. Using her as an object for his convenience. Was that so terrible?

Womb. Weary.

He rests.

With?

Leocadia, like Pepa before her, is weaker physically and emotionally and thus depends on him for protection. She lacks his powers of reason. She is all sense and intuition. She has no principles. She will only do a thing if it is pleasing to her.

Did he think this, or was it just something he read? Was he that alone? Did he feel that abased? The masked bride is free, just as he is. She is her own person, not mere property. She can follow her will, just as he can. They can live as they please.

Lose yourself in this other person, give yourself fully, and get yourself fully back. This “I” here, he says out loud, and this “her”. The old man in exile, the bride on the stairs. Wife, husband, host, guest. In the dark bed. They know not, neither will they ever understand; they sleep on in darkness. All the foundations of the earth are out of course.

They are everyone.

Where?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hexagon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.