This is war

It is not a time for the creative to fail, to shrink, or to stop working. – Pablo Picasso, 1944

1.

Less than 24 hours after the Luftwaffe began raids on Polish cities, Pablo Picasso’s driver, Marcel Boudin, drove Picasso and Dora Maar to the seaside resort town of Royan, on France’s Atlantic coast. Also in the eight-seat, six-metre-long Hispano-Suiza, which Picasso had purchased at a car show on the 27th of June, 1930, were Picasso’s private secretary, Jaime Sabartés, Jaime’s girlfriend, Mercedes Iglesias, and Picasso’s dog, an Afghan hound with a narrow head, giant, drooping ears, gangly legs, enormous feet, a spaniel’s body, and a character described as “willingly domineering, a bit touchy, and not very demonstrative.”

Picasso and his entourage left Paris just after midnight. The couple’s Goyard trunks were strapped to the Hispano-Suiza’s roof. The car trunk – le malle, the car boot – was filled with the others’ bags, Picasso’s painting and sculpting supplies, and Maar’s photography equipment. Nobody had matches or a lighter, so everyone had to light one cigarette from the ember of another. Picasso had a flask of cognac in the glove compartment, which he did not share. He navigated using Michelin maps, which were also in the glove compartment. One of Maar’s eyes was swollen shut. She did not speak to anyone during the journey. Sabartés sat next to her. Iglesias sat in one of the jump seats. The dog was on the floor between them. He was named Kazbek, after the largest mountain in the Caucasus. He slept almost the entire way.

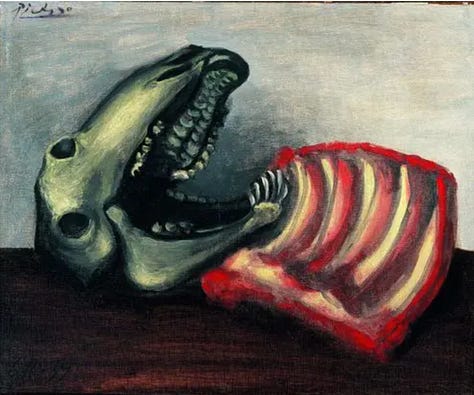

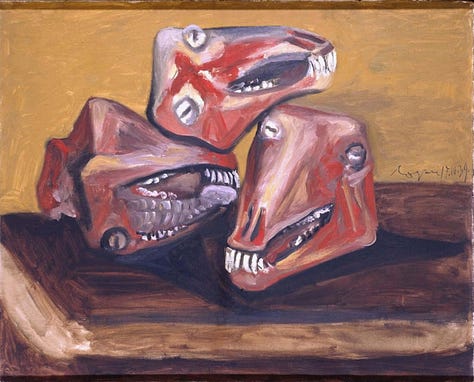

Collaborators, wait-and-seeers, foreigners, deportees, resisters. Are we clear-eyed? Do we have all the facts? Are we paying attention to the right things? They stopped at dawn for coffee and croissants in Saintes and arrived at the Hôtel du Tigre on Royan’s main street at seven in the morning. By then, the French Army had begun its general mobilisation. At 9:00 a.m., a special session of the French Parliament approved an emergency war budget. At 12:30 p.m., France and the United Kingdom issued a joint ultimatum to Germany, demanding the withdrawal of German troops from Polish territory by 5:00 p.m. At noon, France prepared a protocol for a nationwide ban on public dancing. At 1:30 p.m., after lunch at Royan’s best restaurant, the Café des Bains, Picasso rented a room as a studio in the Villa Gerbier des Joncs, where Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s mistress for the last eight years, their four-year-old daughter, Maya, Walter’s sister, Helene, and Walter’s mother, Léontine, had been living since July. The villa was just down from the hotel, on the corner of the Boulevard des Abattoirs. When the shops reopened at 4:00 p.m., Picasso and Jaime visited the slaughterhouses on the boulevard to collect sheep heads for Kazbek.

2.

“As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” – Chuck Prince III, Citigroup, 2007

Dance, dance, dance. Chuck Prince III could bust a groove, but four months later, when losses due to subprime mortgage exposure brought Citigroup to the brink of bankruptcy, he was pushed out of the mosh pit. So far, today’s slammers seem to show more staying power. They move like champions.

Remember how, during the dance marathon, Red Buttons died of a heart attack, and Jane Fonda kept waltzing his corpse around the circuit to avoid elimination? And then how, after she dropped out, she couldn’t shoot herself, so she asked Michael Sarrazin to do it for her? And he did?

Those were not the right things to do.

3.

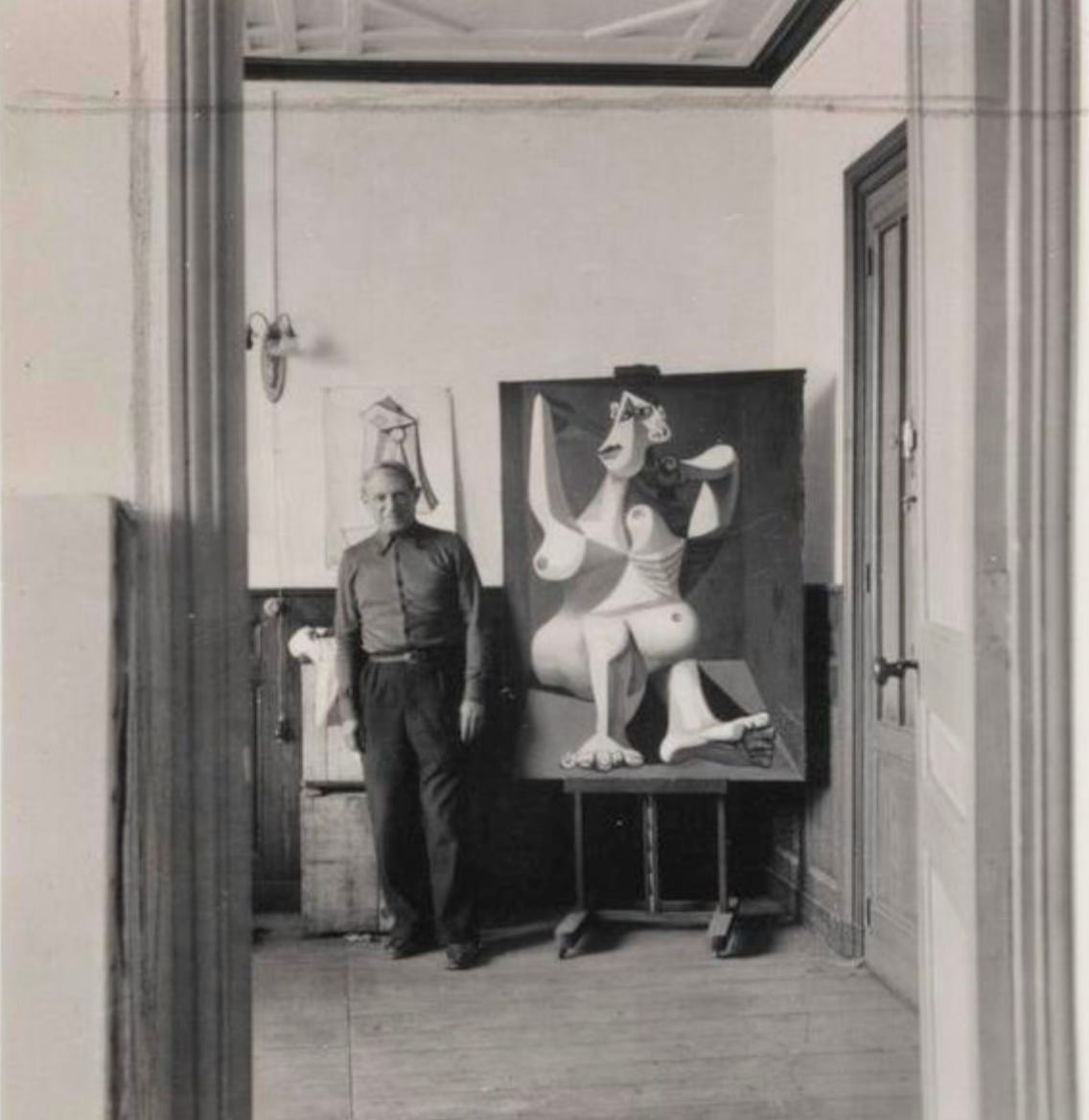

Three months later, in early January, after several trips back to Paris, Picasso rented a large, bright studio in Royan on the third floor of the Villa Les Voiliers, an adjoining annexe of the Grand Hôtel de Paris, at 46 Boulevard Thiers, just above the port. Maar remained in the Hôtel du Tigre, in a single room that also served as her studio and to store Picasso’s paintings. On the 14th of June, as German troops entered Paris, Picasso finished a large portrait of Maar with swastika-forming appendages and cartoon-beast features, including Kazbek’s muzzle and paws. Like most of his wartime depictions of her, she is cruelly disfigured, cut up, tortured, monstrous. “Dora m’a toujours fait peur,” he said. Throughout this period, their quarrels were daily, often leading to an exchange of blows. On several occasions, he beat her unconscious. “Only I know what he is,” she later said. “An instrument of death… not a man… an illness.” And: “All his portraits of me are lies.”

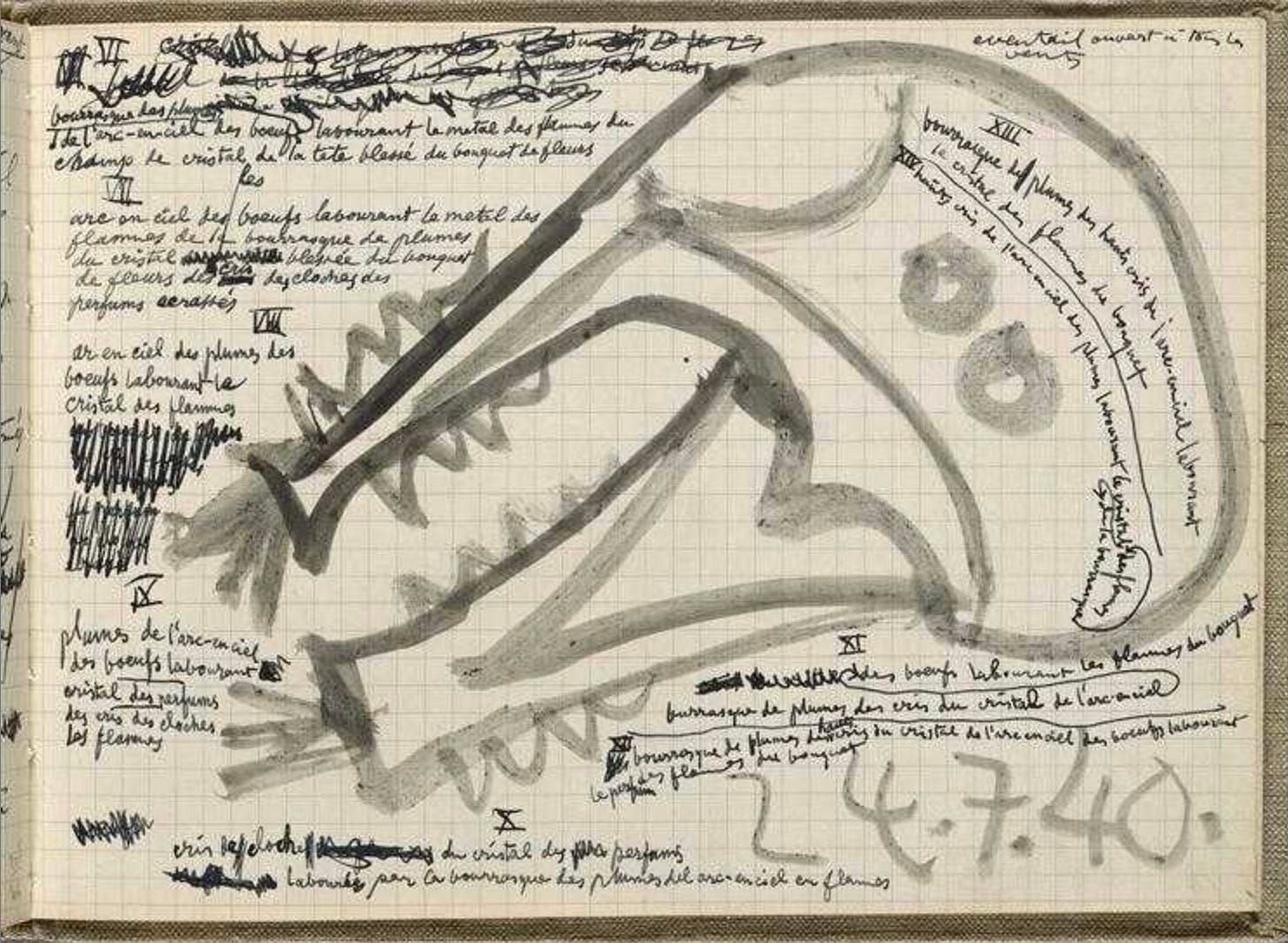

On the 23rd of June 1940, the 44th division of the Wehrmacht marched past his studio window. The officers established their headquarters in the hotel next door. The next morning, in the sixth of eight notebooks he would fill in Royan, after dozens of pages of Kazbek-snouted Maar heads and grotesque animal skulls, Picasso began a new practice of writing a poem a day.

VI fan open to all the gusting winds of feathers of the rainbow oxen plowing the metal of the flames of the crystal field of the wounded head of the bouquet of flowers VII rainbow of oxen plowing the metal of the flames of the gust of feathers of the crystal wounded of the bouquet of flowers of the crosses of the bells of the crushed perfumes VIII rainbow of feathers of the oxen plowing the crystal of the flames IX feathers of the rainbow of oxen plowing crystal of the perfumes of the cries of the bells of the flames X cries of the bells of the crystal of the rainbow of the oxen plowing the flames of the bouquet XI gust of feathers of the cries of the crystal of the rainbow of the oxen plowing the flames of the bouquet XII gust of feathers of the high cries of the crystal of the rainbow of the oxen plowing the scent of the flames of the bouquet XIII whirlwind of feathers of the high cries of the rainbow plowing the crystal of the flames of the bouquet XIV high cries of the rainbow of feathers plowing the crystal of the gust of the flames

4.

A month later, on 15 August 1940, Picasso painted the view below his studio window of the Café des Bains, above. The windows are painted blue to hide the lights inside. The lighthouse is dark. The streets are empty. This is because the night before, resisters gunned down a German sentry at the nearby Hôtel du Golf, which the Germans had requisitioned to headquarter the Kommandatur of the Gironde defence zone, Rear Admiral Hans Michahelles. In retaliation, Michahelles banned the beaches to dogs, Jews and French people. He demanded the mayor’s resignation and ordered his men to hold the city council hostage until the city paid a three million franc tribute. That evening, someone – or perhaps a German plane performing stunts over the harbour – shot out the plate-glass window of the apartment below Picasso’s studio. This brought the police. Picasso, Spanish, was on a watch list. A week later, a tall blond German officer stopped Picasso in the street and gave him the Hitler salute – Picasso responded with a desultory flick of the wrist. The officer asked him what breed his dog was. Picasso, paranoid, stammered a response. The officer clicked his heels and turned away.

Picasso and his entourage returned to occupied Paris that night.

5.

“When a collective abandonment of the criteria for moral judgment occurs… the process is underpinned by an upheaval of the micro-social foundations of human encounters. This is a precursor to the glaring pathos of the ideological exclusion of aliens as enemies. What stands at the beginning is not anti-Semitic furore, organised crime and extermination camps, but rather indifference. My theory holds that the disintegration of morality does not come about suddenly and for no particular reason. Instead, it results from a loss of sovereignty and the ability to shape one’s sphere of personal existence. A fractured relationship with oneself is the precondition for underestimating the effectiveness of changes in social interactions. This enabled charisma – Hitler’s in this case – to unfold its immense power and, in the words of sociologist Max Weber, to upend ‘rules, traditions and, indeed, all concept of anything sacred.’” – Tilman Allert, The Hitler Salute: On the Meaning of a Gesture, 2009.

6.

Paris experienced a cold snap in late December 1940, with temperatures as low as minus 10 degrees Celsius. The Grands-Augustins studio was unheated. Picasso found a coal stove and stole the electric heaters from Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas’s abandoned flat on the rue de Fleurus, but these made little difference, so he set up his workspace in a small bathroom. By January, he had given up making art and was focused on keeping warm and fed. Restaurant fare was paltry. Artichokes, blood sausage, and maybe an old chunk of Camembert were a standby.

Sometimes, the chef downstairs at Le Catalan would access a choice cut of contraband, and a waiter would be sent. Picasso, Sabartés, and Maar would hurry down to tuck into whatever had shown up – on one occasion, a thick slice of Chateaubriand served with a luscious dollop of Béarnaise. He was caught eating this during a surprise police raid and had to pay a hefty fine, which wasn’t a problem, but he was again threatened with deportation.

At a dinner served by liveried valets and majordomos on the top floor of the Avenue Foch apartments of the Argentine billionaires Marcelo and Hortensia Anchorena, in the company of Maar, Jean Cocteau, and Paul Eluard, and under the watchful gaze of a larger-than-life portrait of the Fuhrer, Picasso ate deboned chicken wings and thighs speared between slices of veal on a golden sword, accompanied by all manner of black-market delicacies.

(The 39 works of Picasso that the Anchorenas owned now belong to the French state and are stored in the Picasso Museum in Paris.)

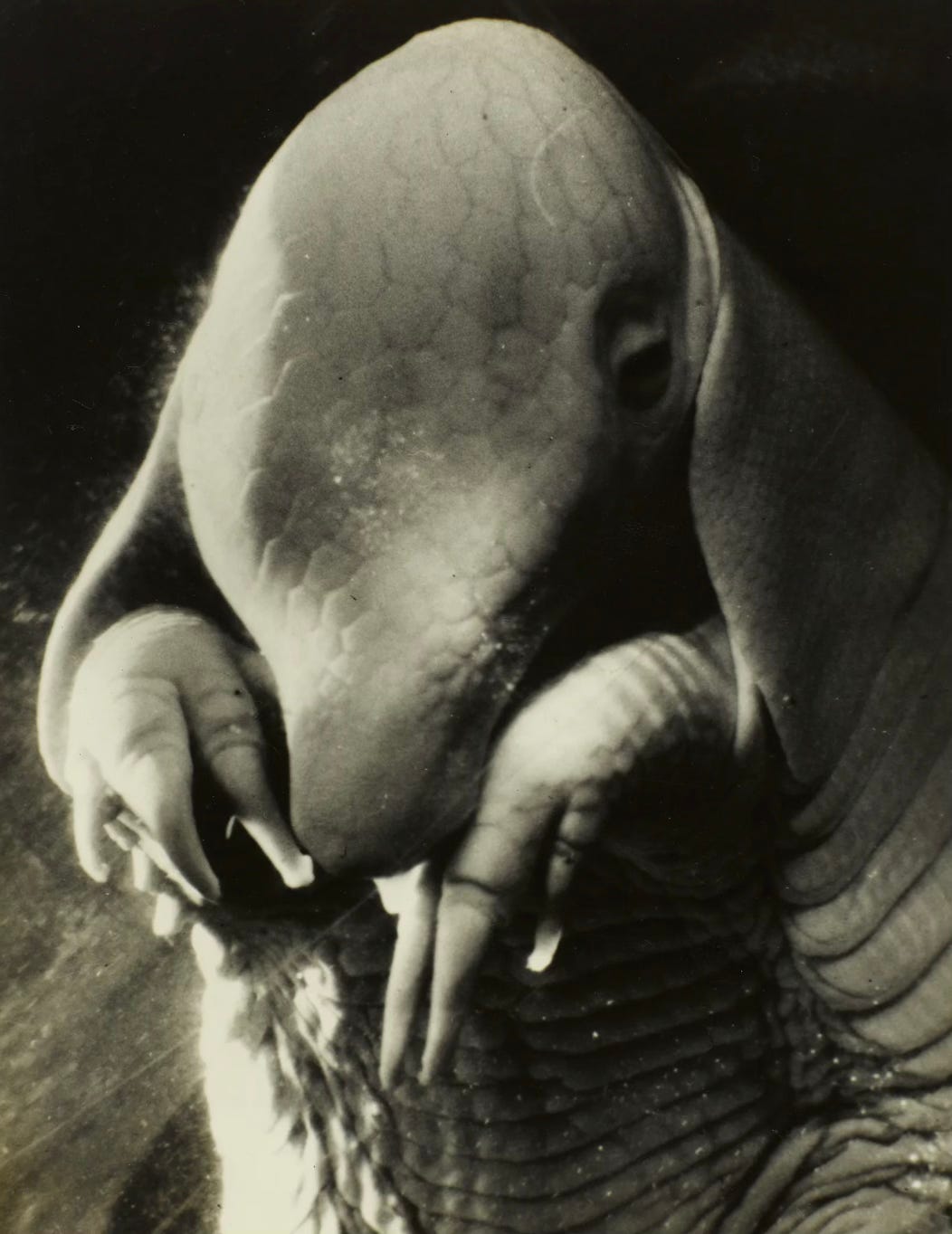

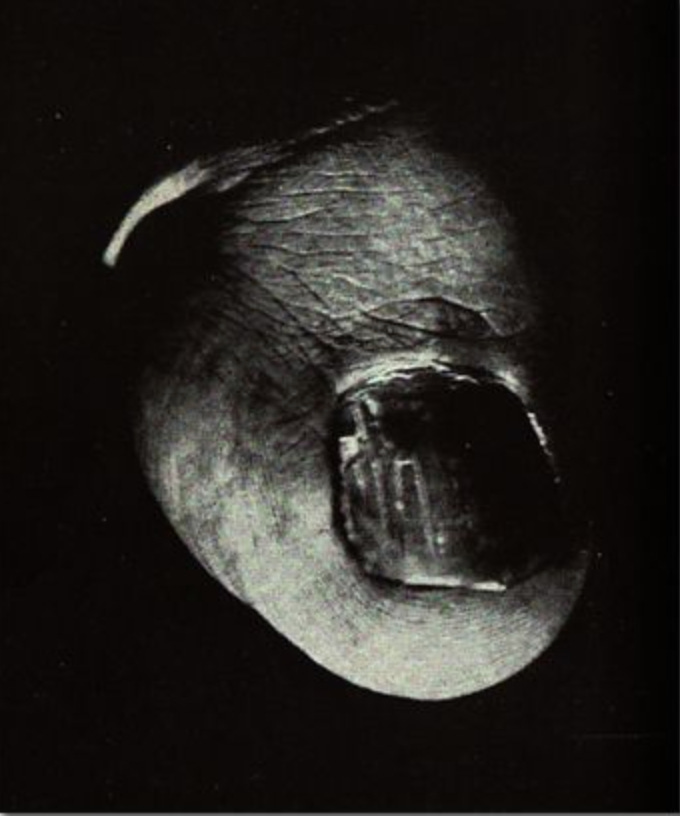

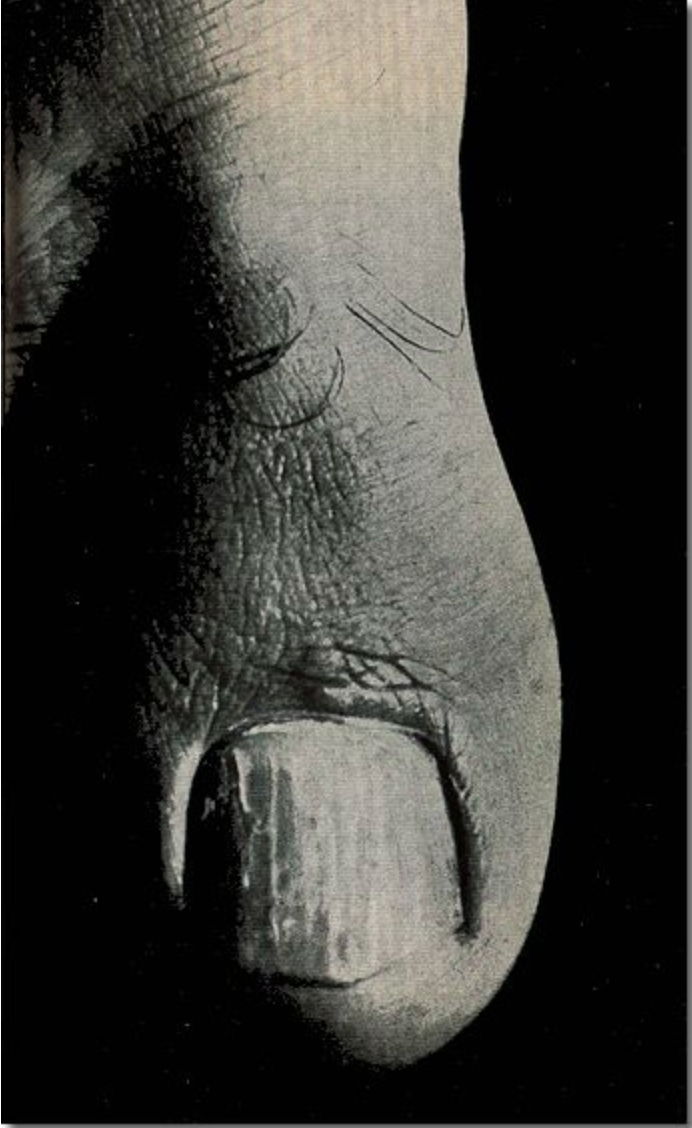

J.-A. Boiffard, Gros orteil. Sujet masculin, trente ans, from Georges Bataille, “Le gros orteil,” Documents 6 (November 1929).

7.

Back at the studio, Picasso began work on a farce in six acts, Le Désir attrapé par la queue (Desire Caught by the Tail/Prick). The parts were written for his friends. Dora Maar was to play Tart, the lover of Jean-Paul Sartre’s character, Big Foot.

The action begins in a hotel corridor. We see the two feet of each guest in front of their room door, writhing in pain:

THE TWO FEET OF ROOM N° III: My frostbites my frostbites my frostbites

THE TWO FEET OF ROOM N° V: My frostbites my frostbites

THE TWO FEET OF ROOM N° I: My frostbites my frostbites my frostbites

THE TWO FEET OF ROOM N° IV: My frostbites my frostbites my frostbites

THE TWO FEET OF ROOM N° II: My frostbites my frostbites my frostbites

The transparent doors light up, and the dancing shadows of five monkeys eating carrots appear. Then everything goes dark. A few minutes later, in ACT III:

BIG FOOT: Upon reflection, nothing beats a lamb stew, but I much prefer miroton or a well-made bourguignon on a happy snowy day, meticulously and jealously prepared by my slave, a Hispano-Moorish and albuminuric cook, servant, and mistress, diluted in the fragrant architectures of the kitchen - the pitch and glue of her detached considerations - nothing beats her gaze and her minced flesh on the calm surface of her queenly movements. Her mood swings, her hot and cold fits stuffed with hatred, are nothing in the middle of the meal but the spur of desire interspersed with sweetness.

At the start of ACT V, TART enters, naked, running.

TART: Good day, good evening, I’m bringing you the orgy, I'm all naked, and I'm dying of thirst, you'll definitely make me a cup of tea and toast with honey. I'm extremely hungry, and I'm so hot! Let me make myself comfortable. Give me fur filled with hairs full of mites that I can cover myself with, but first kiss me on the mouth, and here and here and here and there and everywhere. I must love you for coming like this in slippers like a neighbour and all naked to say hello to you and make you believe that you love me and want to have me against you, little lover that I am for you and absolute mistress of my thoughts for you, such tender worshiper of my charms that you seem to be, Don't be so embarrassed, give me another beautiful kiss - and a thousand more, Now go and make me some tea. Meanwhile, I will cut the callus on my little finger that annoys me.

BIG FOOT takes her in his arms, and they fall to the ground.

TART: (getting up after the hug) You have excellent ways of receiving and taking. I'm covered in snow, and I'm shivering. Bring me a brick (she squats in front of the prompter's box and, facing the audience, pisses and gonorrhoeas for a good ten minutes). Phew, that's better.

She farts - refarts – puts her hair back, sits on the ground and begins the skilful demolition of her toes.

Three years later, the play was performed in the apartment of Picasso’s neighbours on rue des Grands-Augustins, Michel and Louise Leiris. Maar refused to take off her clothes to play Tart, so the part was given to the 23-year-old actress Zanie Campan. Campan’s husband, the poetry publisher and resistance leader Jean Aubier played Les Rideaux (The Curtains). Maar played L’Angoisse mince (Thin Anguish). Also in the cast were the Leirises, Sartre, Raymond Queneau, and Simone de Beauvoir. Albert Camus directed. The Anchorenas brought a big chocolate cake. Maar’s former lover, George Bataille, was in the audience. In his 1929 Surrealist essay, “Le Gros orteil” (“The Big Toe”), he argued that this much-overlooked appendage – “la partie la plus humaine du corps humain” (“the most human part of the human body”) – demonstrates the importance of the “low” and the “base” in human existence, as it is crucial to human evolution and our ability to stand upright and look towards the heavens. The essay was a source of inspiration for Picasso’s play. Also in attendance was Jacques Lacan, who would soon confine Maar in the Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital, where she would ask for and receive electroshock treatment. Over the next nine years, she will have near-daily psychoanalysis sessions with Lacan before converting to Catholicism.

8.

But these are deeds which should not pass away,

And names that must not wither, though the earth

Forgets her empires with a just decay,

The enslavers and the enslaved, their death and birth...

– Lord Byron, "Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage", 1812, cited by Frederic Spotts in The Shameful Peace: How French Artists and Intellectuals Survived the Nazi Occupation, Yale University Press, 2008.

End of Part 1.

“Degenerate" Art: The Trial of Modern Art under Nazism,” Musée Picasso, Paris 3rd. Until May 25.

“The Royan Sketchbooks”, Museo Picasso Malaga. Until March 30.

Let's just say we're all lucky Picasso never went into politics.