Two Penguins, a heron, a swan, a crane, a crow, a raven, a hawk, a dove, a dead swallow, some geese, 30 billion chickens and African skies darkened by quelea quelea

"Wide is the gate and broad is the way that leads to destruction, and there are many who go in by it." Matthew 7:13-14

1.

“The new dimension taken on by foreign interference reveals persistent vulnerabilities, starting with our naivety, which is shared by political and administrative elites as well as economic and academic circles… in terms of espionage and economic interference, our allies are not necessarily our friends either, and various operating methods, such as the extraterritoriality of the law, are being used in particular by the United States of America to capture data and undermine our economic security.” — “Aujourd'hui en France” report, French Parliamentary Delegation on Intelligence, 2 November 2023

A renewable energy gold rush will soon be underway in north-eastern France, where millions of tons of hydrogen have been found deep within the earth’s crust.

France has the capacity to produce 500,000 tonnes of lithium. The overseas French territory of New Caledonia accounts for a quarter of the world's nickel resources. New Caledonia was the world’s eleventh-largest producer of cobalt in 2022, with output up by 30% on 2021. The overseas French department of French Guiana has large deposits of nickel and cobalt.

In the last seven years, European banks have helped the fossil fuel industry raise over €1 trillion in financing. French banks are the most active.

The popular idea that mushrooms communicate and cooperate with trees through the “wood-wide web”, and that trees warn each other about herbivorous insects and other threats, is as yet unfounded. Some fungi are wiping out bat populations. Others are killing off frogs at an even more alarming rate. Donald Trump remains a dangerous menace. Tai Chi can slow the progression of Parkinson’s disease and lower the need for symptom-relieving drugs. In 1968, 15% percent of American men wore girdles. Today, such devices are called “bodyshaping underwear”.

Paris has a new wiener schnitzel sandwich outlet. The schnitzel is made with chicken. There is no such thing as chicken wiener schnitzel. Veal, yes. Pork, chicken, turkey, mutton, beef, celery root, no. These must be called Schnitzel (nach) Wiener Art (“Viennese Schnitzel style”).

The moon is 40 million years older than we thought.

Chickens are the most populous species of bird in the world.

Gaza is being flattened.

2.

“I was about seven years old the first time I actively took part in cooking a chicken without adult supervision.” — Jacques Pepin, Art of the Chicken: A Master Chef’s Paintings, Stories, and Recipes of the Humble Bird, 2023

Jacques Pépin was born in 1935 in the Auvergne town of Bourg-en-Bresse, home of the world’s most famous chicken, le poulet de Bresse.

During the war, such beasts were scarce, and if a young boy chanced upon one in a farmer’s field, it was fair game. Such a chance presented itself to Jacques and his friends on a summer afternoon in 1942. They fell upon it and killed it, and without plucking its feathers, covered it in wet clay from the nearby river. Then they built a fire on the riverbank and buried the bird under its coals.

At the end of the afternoon,

we retrieved the hardened block of clay from the embers of the dying fire and smashed it open with stones. The feathers and skin stayed glued to the clay, leaving behind the meat for us to enjoy. It might not have been a triumph of haute cuisine, but we enjoyed the results immensely and were very proud of ourselves.

I have killed fish and eaten them. I have killed mice, but I did not eat them. I was responsible once for the death of a heron, but I was nowhere near it when it died.

3.

The Inuit hunt Tundra swans from canoes and kayaks with long spears. The meat is apparently excellent; in Europe, especially in France, up to and including the 19th century, swans were considered table delicacies. I can’t imagine eating one. A heron? Maybe. If it was already dead, freshly killed, and entirely prepared by Jacques Pépin.

“The various lights under which a horn may be looked at have given rise to a vast number of words in language,” wrote Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1863. “It may be regarded as a projection, a climax, a badge of strength, power or vigour, a tapering body, a spiral, a wavy object, a bow, a vessel to hold withal or to drink from, a smooth hard material not brittle, stony, metallic or wooden, something sprouting up, something to thrust or push with, a sign of honour or pride, an instrument of music, etc. From the shape, kernel and granum, grain, corn. From the curve of the horn, κορωνις, corona, crown. From the spiral crinis, meaning ringlets, locks. From its being the highest point comes our crown perhaps, in the sense of the top of the head, and the Greek κέρας, horn, and κάρα, head, were evidently identical; then for its sprouting up and growing, compare keren, cornu, κέρας, horn with grow, cresco, grandis, grass, great, groot. For its curving, curvus is probably from the root horn in one of its forms. κορωνη in Greek and corvus, cornix in Latin and crow (perhaps also raven, which may have been craven originally) in English bear a striking resemblance to cornu, curvus. So also γέρανος, crane, heron, herne. Why these birds should derive their names from horn I cannot presume to say.”

4.

The idea of Beggar’s Chicken — chicken wrapped in clay and slow-cooked in coals — originated in Hangzhou thousands of years ago. The following recipe was buried in a Han dynasty tomb in 168 BCE:

Drown a yellow hen in soy paste. Wrap it in silvergrass leaves. Coat it with wet clay and bake it in the fire. When the crust is completely dry, eat the chicken. Use the feathers to fumigate the anus.

Evidently, this was considered a treatment for hemorrhoids. In France, in the 18th century, the anal insufflation of smoke was prescribed for a different reason: resuscitating a drowning victim. According to the polymath Réaumur (1683-1757), there were many effective ways to avoid the “hurried burials” of individuals falsely diagnosed as drowned: insert silver needles in the victim’s big toenail; hang the victim by the feet; pour heated urine into the victim’s mouth; cover the victim’s body with manure; lay the victim between two naked living people; and open the victim’s jugular. But “what is best, perhaps,” wrote Réaumur,

is to blow the smoke of a pipe into the intestines. One of our Academicians has witnessed the swift and happy effect of this smoke on a drowned man. A broken pipe may supply the pipe or blow-torch by which the smoke that is drawn from the whole pipe will be blown into the body. —“Avis pour donner du secours à ceux que l’on croit noyés”) (“Advice to help those thought to have drowned”), 1740

Anal insufflation caught on. In 1740 a Parisian pharmacist named Philip Nicolas Pla installed twenty “fumigation boxes” along the banks of the Seine.

Inside each box was a printed manual, an iron spoon to open the jaws, salts of ammonia to rub under the nostrils, a woollen garment for warmth, and an enema to insufflate tobacco smoke into the anus… Even if one easily understands the use of tobacco (it is considered as an irritant, and therefore a stimulant), the question still remains as to why the anus was the preferred site for insufflation? For some, the origin is more symbolic than pragmatic: perhaps the answers lie in the legendary stories of the storks that hibernate under the water of the lakes, immobile, each having their beak driven into the anus of another . . . or in popular beliefs related to the burlesque resurrections of the medieval Carnival celebrations and the Commedia del’arte. —Charlier Philippe, Deo Saudamini, Annane Djillali, “Letter to the editor: Intra-rectal tobacco insufflation as a resuscitation method for drowning victims: A gold-standard in the 18th century”, Resuscitation 142, 2019

5.

“You ever light fires as a kid?” he asked.

“Fires?”

“Yeah, fires. Or torture small animals?”

“I used to shoot frogs at the frog pond with my slingshot.”

I had forgotten about the WHAM-O slingshot. That’s how they got the name. When the missile hit its target, it makes the sound. WHAM-O! My friend Pete used it to take out bus windows.

“Fed moths to spiders. Knocked down wasp nests. Where's this going?”

“Nowhere, just curious. How about fires? I remember, once, you lit the chesterfield on fire in the den. You were, what, five?”

“A cigarette?”

“A couch, a sofa. Christ. You call yourself Canadian.”

“No I don’t. And I have no memory of lighting a couch on fire.”

“And didn't you and some neighbourhood kid light someone's lawn on fire?”

“Election signs. We'd stuff gasoline-soaked rags between the cardboard faces of the sign, then torch it.”

“Political?”

“No, non-partisan. We did them all, the bigger the better.”

“Just to watch them burn.”

“No, we lit them and ran. Never got to see our handiwork.”

“Not very satisfying.”

“Made all the papers, though. And the evening news.”

“How come I never knew anything about this?”

“Another stunt, we’d leave burning lunch bags filled with dog shit on front porches. Ring the bell and run. Poor guy comes out, stomps on the flames, gets shit all over his shoes.”

“Clever.”

“Anything else you want to know?”

“Have you ever heard of the McDonald Triad?”

“Sounds like the Scottish mafia.”

“Bah-boom.”

“Or the newest Big Meal? With haggis?”

“You’ve heard of it, right?”

“Of course I've heard of it. And so?”

“Also called the Homicidal Triad.”

“Fire-starting, cruelty to animals, and bedwetting.”

“Not just bedwetting. Late bedwetting. After the age of fifteen.”

“Yeah, yeah, and I drove a Volkswagen.”

“So?”

“So at one time it was the serial killer's car of choice.”

“Didn't know that.”

“Ted Bundy et al. Ask the profilers.”

“Did you torture animals?”

“Again, no recollection. Killed that heron that one time, but it wasn't torture. I told you, right?”

“See? Sacrifice. Blood ritual. Rehearsal for future crime.”

“It wasn't torture. It was an accident. The damn thing flew into a car.”

“Because you threw a rock at it.”

“Because I wanted to see it fly. And I didn't throw a rock at it. I threw a rock near it.”

Flapping its heavy wings and lumbering up into the air. Landing up the street. Another rock. Up it goes again, low, great beats in the moonlit night.

“Did you go look at it after? See if it was dead?”

“No, I heard the screech of brakes, the thud. Covered my eyes with my fists and walked the other way.”

“Think of the poor guy in the car.”

“I know.”

“Thinking it was his fault.”

“I went up later, but there was no sign of the bird.”

“Blood?”

“Nothing.”

“And you felt how?”

“How do you think?”

“Don't know. Like Parsifal?”

“Who?”

“Wagner. With his swan. His first trial, when he kills the swan.”

“Say what?”

“The Pure One. The Innocent Fool.”

“I felt terrible. What are you saying?”

6.

“You broke my heart, it came in two.” — Jonny Slut, “Baby Turns Blue”, 2003

“Homo Sapiens — ape’s son, IMHO” — anagram by Noam Elkies, 2003

Usually, for me at least, listening to live music, especially instrumental music, releases swarms of ideas. But at two jazz concerts last weekend, perhaps because the music was exceptional, the mind — I refuse to call it my own anymore — refused to wander. Has it dulled? Is there a standard measurement for dull? Was it ever not dull? Why you ask am I asking you? Because you’re reading this now and I’m writing this now. Two nows, universes apart. This must never be taken for granted. Meaning is soul and sound is flesh. A cognitive explanation might be this: Selecting a word involves a preliminary stage in which a semantically and syntactically specified representation — a lemma — is accessed; and a secondary stage where a phonological representation — a lexeme — is accessed. These are separate nodes in the neural network, but in different “time” zones of the brain. In normal conditions, lemmas and lexemes pop into action almost simultaneously. When they don’t, we get that tip-of-the-tongue thing instead: the thoughts don’t rise above the notes entering through the ears; the birds don’t sing or take flight; or they fall to the ground at our feet, dead. Come in two or come in twos? We only have one tongue with which to speak but just as we have two arms, two legs, two eyes, two ears, two lungs, and two kidneys, we also have two noses with which to breathe and smell. Why?

For an air conditioning unit that works 24/7, 365 days a year it makes sense to have two units in parallel and alternate the airflow from one side to the other over a period of hours. Two noses are therefore very useful as one can go through a rest and cleansing cycle whilst the other takes over the dirty and damaging work filtering and conditioning the 10-20,000 litres of air we breathe in every day. — Ron Eccles, Common Cold Centre, Cardiff University

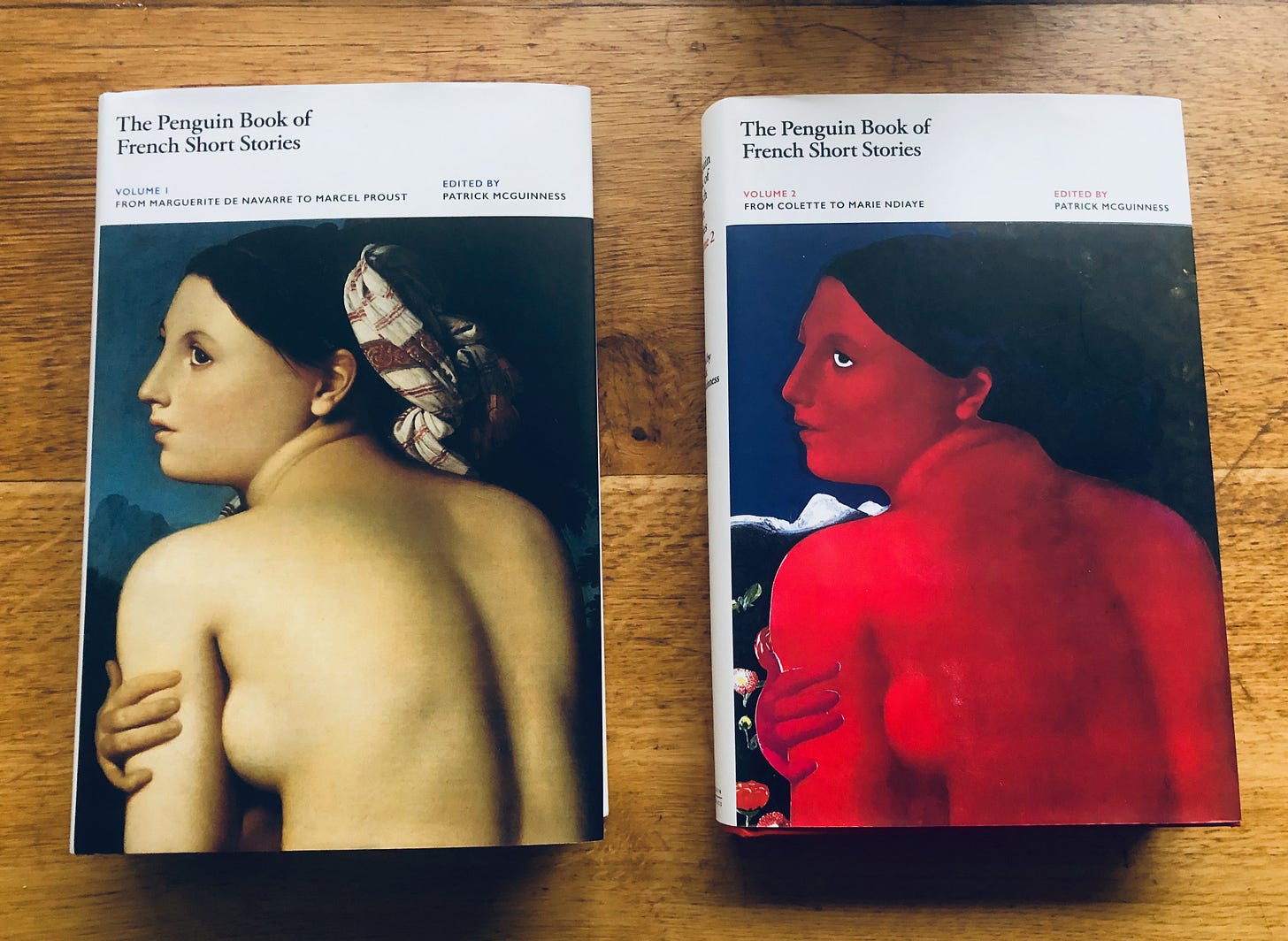

Two, too: this handsome pair of actual books that Penguin sent to my real-world mailbox this week.

They brim with surprises, from the ribald bit at the start by Marguerite de Navarre (1492-1594) to the 1999 acid-trippy love story at the end by Virginie Despentes. The translations by the editor Patrick McGuinness and five others are fluid. Sam Beckett is not included — this is my only serious complaint, that and, perhaps, that the selection is a bit top-heavy with what Anglos-Saxons expect or want from the French — sex romps and rivalries, erotic intrigues, an orgasmic petite mort that leads to a grande mort, conjugal dismemberments, etc. — but most of my favourites are here, including Gustave Flaubert’s, “A Simple Heart”, which I discussed a few weeks ago in my two-piece study here & here of Flaubert’s Bouvard et Pécuchet.

At 31 pages “A Simple Heart” is the longest story in the books. The shortest are the three-liners Félix Fénéon’s wrote between 1905 and 1937 based on French newspaper fait divers (“news items”).

Among these:

“Swimming instructor Renard, whose pupils were disporting themselves in the Marne, at Charenton, entered the water — and drowned.”

And:

“The bones discovered on Ile Verte in Grenoble belong not to two but to four children’s skeletons. Minus two skulls.”

Not included, however: “Bones were discovered in a villa on Ile Verte near Grenoble: those — she admitted — of Mrs P.'s illegitimate children.”

There is also Baron Vivant Denon’s marvellously and perversely complicated “No Tomorrow”. Coincidentally, this story plays a key role in my novel, The Inventions of Goya, now serializing on Hexagon. So does Denon’s own story: besides being a pornographer, the Baron was an accomplished engraver and painter, and the first director of the Louvre.

According to the Baron, who sat at Goya’s right — Stendhal sat to his left — French soldiers, armed with hammers and saws and directed by the Baron himself (he personally selected artworks and other spoils in Egypt, the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and Spain), carefully removed Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata — “carefully, Senor Goya, I assure you” — along with Cimabue's Maestà, which Goya somehow missed seeing in both Pisa and Paris, from the chapel’s walls. The paintings were paraded through the streets of Paris in a half-mile-long convoy of confiscated goods and animals, including eleven elephants and seven giraffes. The following year it was put on permanent display in the ‘primitive’ Italian room of the Louvre. — Christopher Mooney, The Inventions of Goya, page 38

There’s also the puzzling prose poem from Charles Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris — “Knock Out the Poor!”, in which the narrator recounts an event that happened to him 17 years before, when he was still something of an idealist, and when, after spending two weeks holed up in his room reading self-help books, and having “swallowed all the lucubrations of all these entrepreneurs of public happiness— those who advise all the poor to become slaves, and those who persuade them that they are all dethroned kings,” found himself exceptionally thirsty. “Because the passionate taste for bad reading generates a proportional need for the great outdoors and refreshing drinks.” So he headed to a cabaret.

As he was about to enter, he was accosted by an old beggar who handed him his hat, “with one of those unforgettable looks that would topple thrones if mind moved matter, or if the eye of a magnetizer could really ripen grapes.”

Immediately he punched the beggar in the eye. He then clawed at his face, knocked out two of his front teeth and slammed his head repeatedly against a wall. Then he kicked him to the ground and beat him senseless with a tree branch.

Then…

No spoiler. Buy the book. Or read it in the original here.

More to come — once I’ve read the lot.

7.

Listen to this while you read the next paragraph.

Those are the chirps and songs of a massive flock of the second most common species of bird on earth: the red-billed quelea (Quelea quelea in Latin) of the Sub-Sahara.

Small and swallow-like, the quelea is the most common undomesticated bird on earth, with a total post-breeding population of approximately 1.8 billion. A female quelea can lay and hatch as many as three chicks three times a year. They are often called “Africa's feathered locusts” because of the damage they cause to grain crops — a single bird can eat as much as 15 g (0.53 oz) in seeds each day.

What you are hearing in the clip above are not only the chirps and the songs, but, if you listen closely, entire flocks flushing and flying onto thorny bushes, the whirring of wings as they fly from one patch of seed to another, and the rolling cloud of hungry birds at the rear of a flock flying overtop the better-fed members at the front. You can also hear individual birds preening on bushes in the warm early morning sun, and others foraging on grass seed below.

Their most common predators are other birds: herons, storks, raptors, owls, hornbills, rollers, kingfishers and shrikes. Humans eat them too. Between five to ten million are trapped and killed around Lake Chad each year, usually during the moonless period of the night. Basket traps and nets are used. The necks are broken. The feathers are plucked. The next morning, the carcasses are roasted on hot coals. Then they are laid out in the afternoon sun until the trucks of the roadside vendors come to take them to N'Djamena.

A pack of 15 roasted birds costs $1.

8.

Now listen to this.

Beetroot is a poetry podcast hosted by Marta Mcilduff and Lottie Walker. It’s been on the air for four years — their anniversary celebration episode went out on 1 November — and it is consistently excellent. Here’s the duo’s winning formula: “In each episode, they present poems to each other as literary gifts. The pair dissect, swoon and weep, uncovering the joys of poetry for a new generation of literature lovers.”

If you feel you’ve already spent too much time on this page — or, like Baudelaire, after all this bad reading you just desperately need a drink — listen to the Beetroot podcast later, but first fast forward directly to 25:20 and listen to Marta introduce The Odyssey and ever-so-movingly read this passage from Emily Wilson’s translation:

When we die, the sinews no longer hold Flesh and bones together. The fire destroys these As soon as the spirit leaves the white bones, And the ghost flutters off and is gone like a dream. Hurry now to the light, and remember these things, So that later you may tell them all to your wife.’

Thanks for reading and listening. Hope to see you here mid-week for the next chapter of The Inventions of Goya. Hope to see you too among the likes and in the comments, and on the lists of my cherished subscribers.

Or….:

I might have to take a break next week to knock out some ghost-writing and editing assignments. I’d rather not, I’d rather stay well within the walls and warmth of my Hexagon home, but the wolves are at all six doors and Christmas is coming fast.

So, regrettably, once more, it is time to cudgel my way out into the moonless night, lay out the nets and the basket traps, and start collecting wood for the morning fire.

PS. Chickens, in the ancient Greek world, were gifts exchanged by lovers, not meat for the table. In the Odyssey, Penelope keeps geese as pets, and in a dream, an eagle flies down from the mountains and breaks the necks of twenty.

Birds abound in the Odyssey, twenty-one species are named, from nightingales to falcons to bearded vultures.

Athena has owl eyes and as Odysseus lets the arrows fly, she flits up to perch on a rafter in the form of a house martin.

Two eagles tear each other to death; later, an eagle flies by with a swallow in its mouth. Another eagle flies by with a goose in its claws. As does a hawk with a dove.

There was something else. What was it? It’s on the tip of my tongue.

9.

I have forgotten the word that I wanted to say. On clipped wings the blind swallow will return To the palace of shades to play with the transparent ones. A night song is sung in forgetfulness. You couldn’t hear a bird. The immortelle doesn’t bloom. The manes of night’s herd of horses are transparent. An empty canoe glides on a waterless river. The word is forgotten amidst the grasshoppers. And it swells slowly, like a tent or temple, One moment suddenly pretends to be the crazed Antigone, Lands at one’s feet the next, like a dead swallow, With Stygian tenderness and a green branch. O, if I could bring back the shame of seeing fingers And the rounded joy of recognition. I am so afraid of the Aonides’ weeping, Of mist, ringing, the abyss. Yet the power to love and recognize is given to mortals, For them even the sound pours through their fingers, But I forgot what I wanted to say, And the unbodied thought will return to the palace of shades. The transparent [thought] keeps on repeating the wrong thing, Again and again: swallow, friend, Antigone . . . But on the lips, like black ice, burns The remembrance of the Stygian ringing. [Variant] But on the lips, like black ice, [it] burns, And torments memory: the word is lacking. You can’t invent it; [the word] itself is droning And rocking the bell of nightly forgetfulness. — Osip Mandelstam, “I have forgotten the word I wanted to say”, 1928. (Unpublished translation by Jane Miller in Mikhail Gronas's "Just What Word Did Mandel’shtam Forget? A Mnemopoetic Solution to the Problem of Saussure’s Anagrams" in Poetics Today, 30:2, 2016.)

Two more book recommendations, both from NYRB: The Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam (NYRB) and Novels in Three-Lines, introduced and translated by Lucy Sante.

Question for my readers: What is the word Mandelstam forgot? Whoever answers correctly wins a prize.

Ta.

Following your trip to Crete, make your way to the coast of northern California.

Where you can watch vultures ride the thermal winds, that let then race across the cliff faces by just holding fast.

Lovely. Come to Crete someday, and see the majestic bearded vultures that soar above our place.