In a solitary chamber, or rather cell, at the top of the house, and separated from all the other apartments by a gallery and staircase, I kept my workshop of filthy creation; my eyeballs were starting from their sockets in attending to the details of my employment. – Mary Shelley, 1818

He was surprised to find himself still at his worktable, still in the high-backed chair, yet slumped forward, his face flattened against the sketch he had started working on the day before. The images confused him, and he felt sick.

He often felt sick. Not just in body but in spirit. He was sick of banalities and pretensions. He was sick of things. Sick of lying, sick of recreating lies. Sick of fawning and flattering, though let us be clear: he never fawned or flattered. He solicited work and position but always on his terms. He painted kings and bankers but also dwarves, saints, rebels, and prostitutes; it didn’t matter, he showed them as they were, sufferers and sinners alone in the world. But the sickness grew stronger. Sick of surfaces. Sick of status. And then sick in his stocky peasant body, physically sick. He was wracked with fevers, visions, voices, demons.

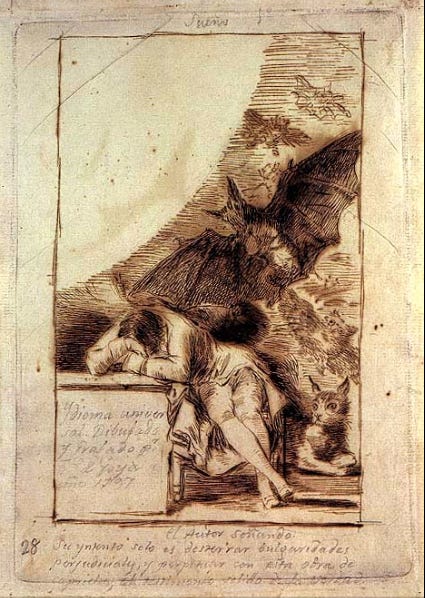

The drawing under his nose, on which pooled his drool, was first intended to be the frontispiece of Los Caprichos. The man in it, him, slumped like him, sitting at the desk in the high-backed chair alone in the night, a black spot, his left eye, turned towards us. His fingers are interlaced as if he is praying, and a dark solar aura, radiating strokes of black ink, flows out of his body. Pale beings float in the emanations: bats and owls under the cross-hatchings, two donkeys above, and a vortex of grotesques rise out of the black lines and out of him, and three of the faces are his own, including one, wrinkled and limp, elongated as if in a distorting mirror, like Michelangelo’s slack, empty face smeared onto the flayed skin of St Bartholomew in the Sistine Chapel.

What is the owl with the pen whispering into his ear? Scribbled in his notes: "Title page for this work: When men do not hear the cry of reason, everything becomes visions. Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders."

The cry or the scream? Are bats and owls impossible monsters? He is tired of resemblances. He is tired of one thing calling up another. He loathes comparisons. The symbol of wisdom, the owl, and the symbol of folly. Of sorcery. Of corruption. Of serenity. Leviticus puts it in all its manifestations – the little owl, the eagle owl, the fisher owl, the long-eared owl, the short-eared owl, the screech owl, the great owl, the desert owl, the horned owl – first among the unclean birds. Abominations not to be eaten, touched, or even looked at. But he, he loved owls, didn’t he? Didn’t he love owls? Didn’t he love all birds? And these ones, have they just landed, or are they about to take flight? And the bats, the great black cloud, also on the list of Leviticus, were they flying towards him or away?

He had laid his head down to relieve his anguish, but it clung to him, unmoved. This he knows, this vital congruity, which was described in the book he feebly skimmed just the day before, Un antídoto contra el ateísmo, a gift from Jovellanos ("for the amusement and elucidation of my enlightened friend and fellow witch hunter").

Other words rose in the air. He felt himself to be divisible and impenetrably solid yet surrounded and confounded by the indivisible and penetrable. Substance and its opposite stretched out, filling space, just like the orb of light in the top left corner of the sketch beneath his head. This light made it possible to distinguish things and beings from one another. It, too, was extendable and penetrable. A knife could not divide it; no part was separate from the whole. Any change at its core in colour or brightness altered its every aspect. Was it the sun? No. The sun was not yet up or had already gone down. The moon, then.

Moratín had recently told him, in fact, he had written this down in a letter that he still had somewhere, that it is the custom of the Issedones, an ancient people of Central Asia, that whenever a male elder dies, all his kinfolk bring dead owls and bats of every stripe, and cut up the flesh along with the flesh of the dead man, and throw it all in a giant stew pot for a feast. As for the dead man’s head, it is stripped, cleaned, gilded and preserved as a holy relic, to which a solemn offering is made every year.

This is what he wants for his head.

I am not worthy. I bow to your grand mal search and seizure. I reach for the non-alcoholic gin and tonic-clonic, my faux hand repeatedly hitting my forehead. To and fro, my fevered foe, you have revived the beast, given life to Mary Shelley. Thank you for the a-ha moment!