Cancelled on Substack: An Agapastic reverie of sorts

“Have you any dreams you'd like to sell?”—Stephanie Nicks

A sad thing it was, no doubt, very sad; but we can’t mend it. Therefore let us make the best of a bad matter; and, as it is impossible to hammer anything out of it for moral purposes, let us treat it aesthetically and see if it will turn to account in that way. — Thomas De Quincey, “Murder as One of the Fine Arts”, 1827

We smugly left Paris before the Olympic Games started. The people who stayed behind are now even smugger. That’s the thing about smugness. It’s not only ridiculous sounding, it’s a ridiculous cognitive bias, not unlike the Dunning–Kruger effect, except, instead of ridiculous people being so ridiculous they don’t know they're ridiculous, it’s ridiculously vain people being at least four times more ridiculous than that.

Buddhist doctrine identifies it as mada, one of the twenty subsidiary unwholesome mental factors. I don’t know about that. But then, I don’t know much about anything. But what I do know is what I like, and what I think. I was going to write about novelty — the value of saying something original or unusual — and how in the vague fog of ideas in which we shroud ourselves, there is nothing new, and though that nothing comes from nothing (creatio ex nihilo) and creation is, paradoxically, ongoing (creatio continua), it is imperative to keep in mind just how critical reflection, accident, mixture, separation and mutation are, especially in writing, and, I guess, music, and art, especially in their most avant-garde forms, which, now, ironically, feel ridiculously old and stuffy. I was also going to write about long Covid and paradigm changes in the history of ideas and the philosophy of mind, and C.S. Pierce’s description of evolution by either fortuitous variation, mechanical necessity, or creative love, and how this third mode — creative love — which Pierce called the agapastic mode, requires the adoption of certain mental tendencies, “not altogether heedlessly… nor quite blindly by the mere force of circumstances or of logic… but by

an immediate attraction for the idea itself, whose nature is divined before the mind possesses it by the power of sympathy, that is, by virtue of the continuity of mind; and this mental tendency may be of three varieties, as follows. First, it may affect a whole people or community in its collective personality, and be thence communicated to such individuals as are in powerfully sympathetic connection with the collective people, although they may be intellectually incapable of attaining the idea by their private understandings or even perhaps of consciously apprehending it. Second, it may affect a private person directly, yet so that he is only enabled to apprehend the idea, or to appreciate its attractiveness, by virtue of his sympathy with his neighbours, under the influence of a striking experience or development of thought. The conversion of St. Paul may be taken as an example of what is meant. Third, it may affect an individual, independently of his human affections, by virtue of an attraction it exercises upon his mind, even before he has comprehended it. This is the phenomenon which has been well called the divination of genius; for it is due to the continuity between the man’s mind and the Most High.

I was also thinking about writing about the wild animals I saw last month: three grey whales, a humpback whale, five black bears, five river otters, two deer, two seals, a sea lion, some robins, some house finches, three Stellar jays, dozens of bald eagles, two ospreys, many crows, ravens and magpies, many hummingbirds, many sparrows, many pigeons, many seagulls, a few snakes, one rat, one jellyfish, dozens of crabs, hundreds of sea urchins, thousands of anemones, one sea cucumber, three squirrels, and countless chitons, starfish, banana slugs, caterpillars, earwigs, earthworms, bees, flies and mosquitoes. Add to this the wild animals I only heard — thrushes, woodpeckers, olive-sided flycatchers, yellow-rumped warblers and dark-eyed junkos — and those I ate — spring and sockeye salmon, halibut, black cod, ling cod, eel, tuna, butterfish, prawns, oysters, moose and two unidentified bugs swallowed during forest trail runs in Pacific Spirit Park.

Then I started noticing how more people were leaving lids and seats in public toilets up. At least in this part of the world. So I quite naturally started thinking about saying something about whether the leaving of seats and lids up or down was the right thing to do, the proper protocol, the thoughtful gesture, the most hygienic, because, well, I have to say, it has become complicated, especially in the new gender-inclusive context.

Then an old friend, let’s call him Virgil1, took me on a voyage through Hell, let’s call it the Downtown Eastside.

We were accompanied by a new friend, a photographer from Okinawa2 with the Kanji characters 禅 — zen — tattooed on his left arm. This is thought to be a transliteration of the Sanskrit word dhyana, which means “to consider quietly.” Which, I have to say, was precisely what we were doing. Not just quietly, in absolute silence. It was and is, I have to say, too much to comment on.

Who, even with untrammeled words and many attempts at telling, ever could recount in full the blood and wounds that I now saw?—Inferno 28

I have to say. Why? I have to say used to mean I have to admit, signalling a concession — a weakness in one’s reasoning, a deviation from one’s usual stance, an exception to one’s general belief — often accompanied by a feeling of surprise that this was the case. Now, it’s just empty filler. Or, at best, it means I have to say, as in having a say, as in I feel compelled to express an opinion. Unlike the older, better, less confusing “I must say,” which we use to emphasize a critical remark, such as: “I must say, I don’t give a shit what you have to say.”

Is it just me, or am I hearing “I have to say” more often? Or is its use more prevalent in the excessively punditized part of the world — North America, where I’ve been holed up since June — than elsewhere? Why would this be? I have to admit, I’m mystified.

Up, I think, is the correct position. Seat and lid. I don’t have to say this, but I will. Seat and lid, seat and lid, an eternal repetition of unalterable sequences.

I once overheard a woman in this part of the world opine: “If I were a cattle farmer and this was my herd, I would cull the bottom third. They’re too far gone, nothing can save them. The rest, touch and go. Build new barns, give them extra feed, hope for the best.”

How many can be saved? Saved for what? The slaughterhouse? Words get the job done, but they are not for the faint of heart. They tether people to what they believe is real — love, Israel, sex, death, capital, Wagner, oil on canvas, off the port quarter — and they just as quickly cripple and enslave as heal and liberate. Think of the mirror, the first time — seeing yourself, yet seeing another; seeing another, yet seeing yourself. This first face-to-face confrontation with one’s self is as dark and soul-piercing as it gets. Or so, I have to say, I have been told.

I have to say. Do you have to listen? Of course not. I no longer read opinion pieces. Should you? Probably not. I still enjoy reading other people’s private journals, but I don’t keep one myself because I don’t find anything about my life even remotely interesting — certainly not worth recording for posterity — especially my so-called inner thoughts. Inside and out, I bore myself stiff. If I could give myself the slip, I would.

I find myself, in truth, like Dante, “on the brink of a valley of a sad abyss that gathers the thunder of an infinite howling.” It is so dark, and deep, and clouded that I can see nothing by staring into its depths. I suppose that’s why I drink.

[Probably not the best moment to hit you up, but:

]

As for dreams — mine, not yours, yours fascinate me, just as you fascinate me, and I will hang on your every word, should you decide to leave a comment) — if I don’t pay attention to what I think and do in my semi-conscious life, why pick through the overflow rubbish mouldering in my unconscious?

I sure as shit won’t write it down.

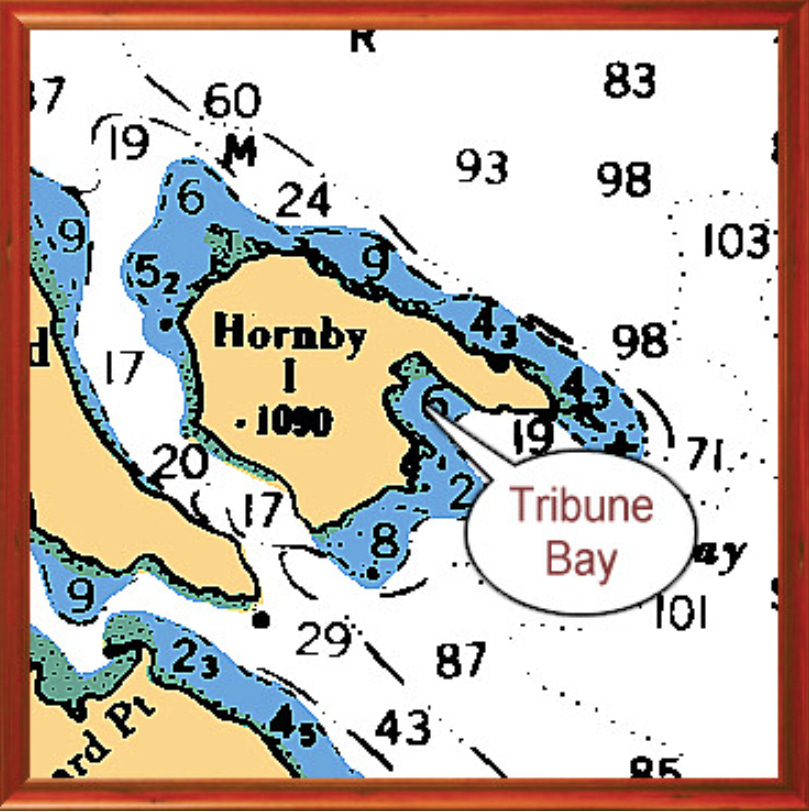

Last night’s dream, however, was different. I sensed this as soon as it pushed out of me at 5:12 a.m., as abrupt and violent as the wolf eel that, a half-century before, lunged from its creviced lair when I was swimming in the sandstone shallows off Tribune and sunk its fangs into my flank, puncturing my liver.

I tried to ignore it — not the eel, the eel was unignorable — and go back to sleep and, through deep breathing and the alphabet hack, stop the ear-worming soundtrack that accompanied it —

Oh, thunder only happens when it's rainin'

Players only love you when they're playin'

— just as it has accompanied every waking and sleeping moment, including this one, since I heard the song from which it spawned performed, with naked and touching sincerity, on an open-mike night at the Bamfield Wreckage three weeks before. An Eagles song, I thought. Yet, when I tried to find it — to listen to it from start to finish — for this is how I am told one rids one’s self and soul of earworms — the entering of “thunder”, “raining”, and “Eagles” produced this:

I gazed at the screen. It was raining. A bald eagle shrieked from its nest at the top of the cedar tree above our bed. My heart froze. Then I saw, at the bottom of the screen:

I closed the laptop. “I need silence,” I thought, half-conscious, the ghost square of afterimaged screen light still flashing in my closed eyes. “And peace. And, above all, sleep.” None of these was to be mine, however, so instead, I re-opened the screen (which, by the way, has about ten times more germs on it than a toilet seat, including faecal bacteria and E. coli) and clicked into a new post page on Substack — this very page — and wrote down the dream that had awakened me using these very words, not entirely in this order but precisely in this form from this point on:

I have been forced to close down Hexagon because of something I wrote or said — I’m not sure which. It had something to do with Buddhism. The reaction to it wasn’t online; it was in a public place crowded with witnesses. Circling the witnesses were hundreds of bystanders, and beyond them, at least a thousand onlookers.

[Remember, this was a dream.]

What the Buddhist thing was, I cannot say. I did not kill any of the animals listed above. This could be construed as a Buddhist thing: “I shall abstain from destroying any breathing beings.” Nor did I see or hear their killing or request it. But I have killed animals in the past. And I have witnessed the death of other animals, and heard their struggles and screams. There is a story about the Buddha and a swan, which Wagner cribbed for Parsifal. Siddhartha’s cousin sees a swan flying overhead and shoots it out of the sky. The boys run to get the swan. Siddhartha is faster. He reaches the bird first and finds it alive. He looks into its eyes, and a flash of recollection overcomes him — he, too, once, had himself been a swan. A great sadness grips his heart. He gently pulls the arrow from the great swan’s wing, staunches its wounds with leaves, whispers prayers to it and soothes it with soft strokes of his gentle hand. His cousin arrives, breathless. “Give me my bird, I shot it down, it belongs to me,” he says. “No,” says Siddhartha. “It is not yours. It belongs to the sky, to which it will return as soon as it recovers. Until then, it is mine, as I have saved its life.” His cousin protests. “Then we shall go the Court of the Elders and ask to whom the swan belongs,” says Siddhartha. The cousin agrees, and off they go to the Court to tell them of their quarrel. The Elders announce their decision: “A life must belong to the man who tries to save it, not to he who tries to destroy it. By right, the wounded bird belongs to Siddhartha.”

In another story, the Buddha, reborn as a rabbit, offers his body as a gift to a hungry beggar by springing up and “like a royal swan alighting on a cluster of lotuses in an ecstasy of joy”, throwing himself unto a blazing fire. But the fire does not burn the rabbit. Doesn’t even singe it.

“Good Brahmin,” it says to the beggar, “the fire is icy-cold: it fails to heat even the pores of the hair on my body. What is the meaning of this?”

“Wise sir, I am no brahmin. I am Sakka, the king of the gods, and I have come to put your virtue to the test." The rabbit replies, “If not only you, Sakka, but all the inhabitants of the world were to try to test me in this matter, they would never find me unwilling to give.” And with this, he utters a cry of exultation like a lion roaring.

Achieving enlightenment — an exultant state of inner peace and wisdom — is a Buddhist thing. Not killing, not stealing, not misusing sexual energy, not lying, not indulging in intoxicants — these, too, are Buddhist things, as are mindfulness (sati), keen investigation of the dhamma (dhammavicaya), energy (viriya), rapture or happiness (piti), calm (passaddhi), concentration (samadhi) and equanimity (upekkha). Then there is the twelve-linked chain of causality, which starts with ignorance (avidyā), which gives rise to action (samskāra), which causes consciousness (vijnāna), which in turn causes name and form (nāma-rūpa), which bring into play the six sensory organs (shad-āyatana) which cause contact (sparsha), which causes sensation (vedanā), which causes desire (trishnā), which causes attachment (upadāna), which causes existence (bhava); which brings about birth (jāti); which spawns ageing, which leads to death (jarā-marana).

“How could you be so stupid,” hissed someone from Substack. A top brass guy, not hiding his animosity. He loathes me, I thought, but why? What have I done? Until now, just now on these very pages, I have never publicly discussed Buddhism. I’m hardly an expert now, though I’ve certainly since learned a thing or two, but at the time of the dream, I was ignorant, stuck fast at the first link in the chain of causality, which is the cycle of delusion and the source of all suffering. I felt awful and sorry, and I expressed this; I was very apologetic, and although my apologies were sincere, the crowd pressed closer, braying and hissing, forcing me to stumble backwards in retreat over the uneven ground beneath my feet.

Then another Substack person appeared, a woman in her late 30s. She was livid. And beautiful. And smart. And overwrought. This was the main word that came to mind at the time — overwrought — and I felt terrible about using it — thinking it, dreaming it — because it’s as misogynistic a slur as “hysterical” — and typical for a man like me to use to describe a woman like her.

“What the hell were you thinking?” she shrieked, her face contorted with rage. “Especially in the context of the Buddhist thing!”

Now here you go again

You say you want your freedom

Well, who am I to keep you down?

It's only right that you should

Play the way you feel it

But listen carefully

To the sound of your loneliness

How can you suspend consciousness with Stevie Nicks looping 47-year-old nonsense in your ear?

Recap: I did not know what the Buddhist thing was, but I knew I was supposed to, and this embarrassed me, for whatever it was, judging by the seething crowd around me, it was a source of collective trauma and great shame. It had rocked Substack on its heels, along with the millions of people who use it. Everyone knew this. Except me. I was too selfish, too cosseted, too far up my own ass to have bothered to keep track of what of importance was happening around me. The Buddhist thing had blown up, and I had made it worse.

“I don’t know,” I said meekly. “I don’t remember.”

This produced even louder shrieks from the seething crowd.

“Do you want me to…” I started, but couldn’t think of the right word to finish the question. Quit? Resign? Stop?

The woman snorted, came close and said, “Not only that, you’re never going to write about this or talk about it. Anywhere. To anyone.” She swung her arm in a wide circling flourish, and her hand caught me on the chin, by accident probably, but it startled me just the same; and by now, the seething, hissing, wolf-eel faced crowd had pressed in too, but some of the faces were starting to change, as if becalmed. Were they now on my side? Suddenly, somehow, the momentum seemed to be shifting in my direction. I was on the right side, and because of this, I became righteous, as was my right, and more than a little smug, because it felt good, but I was having difficulty articulating this new and novel position. For two reasons: one, because I wasn’t capable of being articulate, I was tongue-tied and stupid; and two, because I didn’t know what had happened, what I had written, except that it was outrageous in the context of the Buddhist thing. I found this weird and wildly unfair.

He who knows doesn’t speak. He who speaks doesn’t know. In the context of the Buddhist thing — just now, an image, a yellow robe, and beneath it, my old, grubby sneakers.

A jet now, overhead, contrailing keywords — “thunder”, “raining” “who am I”, “mad”, “lost” — from the lyrics to “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac. The birds in the cedars and hemlocks above my bed began singing Greek choruses. Something was falling through me. My grip on who I was and what the world was was disappearing. Was I becoming Buddha, one of those mountaintop monks, nothing growing but hair and nails? Or a rabbit readying to jump on red-hot coals? Or an islander waiting for a cargo plane to come down from the heavens bearing gifts from the gods? All this, all these words, the lighting of fires along fake runways, sitting in a wooden box under a bamboo transmitter, wearing coconut headphones?

A celebrated handful of Nachi monks became Buddha by running up and down a mountain and eating nothing but nuts for a thousand days until every impurity and ounce of fat had been cleansed and burned away. Then, they sat in the lotus position in a sealed cave deep inside the mountain, surrounded by candles, until their skin became parchment dry. Some drank lacquer through a bamboo straw, turning their guts into glass.

Did they feel smug?

I tried again: “I don’t know what happens in the schoolyard, the alley, the hallway…” I kept trying to find the right spatial metaphor. Perhaps I was influenced by Virgil’s recounting of his recent dream — which he wrote down — about being in a hallway entirely composed of beautifully built doors, each leading to different possibilities. But I had no exit points, no instruments, no concepts, no means to measure or escape the structure of the world.

Philosophy, Peirce stated:

…contends itself with a more attentive scrutiny and comparison of the facts of everyday life, such as present themselves to every adult and sane person, and for the most part in every day an hour of his life.

Suddenly, C. was at my side—not to support me, but because she was angry at me for covering our front hallway and atrium (which was not our actual hallway, and we do not have an atrium) with figurative paintings and tableaux, which I thought were excellent, but she thought were awful. She especially didn’t like one face, which she pointed at and said, “And this guy? A cook?” And then she stomped off.

I repainted everything — white — and again, got the momentum back and started to feel smug because the result, again, was excellent. But only one other person saw it — my friend Jean-Phi, a seismic engineer who was coming over for a drink.

And then, enraptured by this thought, I woke up. And tried to go back to sleep.

Like a heartbeat drives you mad

In the stillness of remembering what you had

And what you lost

And what you had

And what you lost

And then wrote this down.

And decided it was time to take a couple of weeks off.

—BAMFIELD, B.C., 12 August 2024

1. Down

2. People are overwrought, over-sensitive and over-programmed. Use “overwrought” all you want. Use it unsparingly.

3. In fact, thunder does not only happen when it’s raining and it’s weird to contend otherwise. However, it is true that players only love you when they’re playing.

4. Enjoy the break.

Good decision! Enjoy your time and hang the rest. For now.