Folly

"I feel like the Israelites in the desert coming across manna, and thinking: what the fuck is this?" – Philip Larkin

LARKIN ABOUT today, writing this while reading that, that being Larkin’s letters and some of his glummer poems, while thinking about Christmas stuff(ing) and trying not to overhear Bing, Dean, Mariah, and Vince Guaraldi looping endlessly up the stairs while KNOWING how utterly inappropriate Goya is at this time of year, esp. after all the hits we’ve taken & & & while all the while trying to endeavour to make more sense of more senseless things, a dangerous pastime, especially with grim old Phil Larkin lurking among the “sullen fleshy inarticulate men, stockbrokers, sellers of goods... men whose first coronary is coming like Christmas; who drift, loaded helplessly with commitments and obligations and necessary observances, into the darkening avenues of age and incapacity, deserted by everything that once made life sweet.”

'You look as if you wished the place in Hell,'//My friend said, 'judging from your face.' 'Oh well,//I suppose it's not the place's fault,' I said.//'Nothing, like something, happens anywhere.'

A fuck-up for sure, old Phil, a drunken, abusive, racist bigot sexist wanker blah blah with, fortunately for him, the poor rotten-begotten-every-evening-competely-sotten bastard, his old mum and dad to sop up most of the blame.

They may not mean to, but they do.//They fill you with the faults they had//And add some extra, just for you.

Old Phil didn’t have kids, though, did he? They’ll do you a doozy.

"Until I grew up I thought I hated everybody, but when I grew up I realized it was just children I didn't like. Once you started meeting grown-ups life was much pleasanter. Children are very horrible, aren't they? Selfish, noisy, cruel, vulgar little brutes." – Larkin’s interview in The Observer, 1979.

2.

“What an awful time of year this is! Just as one is feeling that if one can just hold on if it just won’t get any worse, then all this Christmas idiocy bursts upon one like a slavering Niagara of nonsense and completely wrecks one’s entire frame.” — Larkin’s letter to Judy Egerton, December 1958.

“The thought of Christmas depresses me… Every year I swear I’ll never endure it again, & make you promise to be sensible, & now here you are talking about duck again, just as if I had never shouted and got drunk & broken the furniture out of sheer rage at it all… To hell with Christmas. Let us have peace, & not all this blasted cooking and eating (and washing up!)” — Larkin’s letter to his mum, November 1971.

Okay, got those off the chest. Time for cheer. Who doesn’t love Christmas? We’ve so much to be thankful for, especially now that the godawful King’s Singers are no longer lofting bemoaningly out of the kitchen speaker. And just look at all the delicious Christmas mince and manna!

But just as I’m about to don me now here comes scroogy old Phil again:

Man hands on misery to man.//It deepens like a coastal shelf.//Get out as early as you can,//And don’t have any kids yourself.

Jesus.

Isolate rather this element / That spreads through other lives like a tree

And sways them on in a sort of sense

And say why it never worked for me.

Something to do with violence

A long way back, and wrong rewards,

And arrogant eternity.

And that damn duck again: “I’m afraid I was not a very nice creature when at home. I wish I could explain the very real rage & irritation I feel: probably only a psychiatrist could do so. It may be something to do with never having got away from home. Or it may be my concern for you & blame for not doing more for you cloaking itself in anger. I do appreciate your courageous struggle to keep going in the old way, and am aware of your kindnesses – I did enjoy the duck, and all the other things – but I am worried about how long you can carry on without help.” – Larkin’s letter to his mum, December 1970.

Fuck duck. We’re having turkey.

3.

“From St. John’s, news of another garden party (at the last I was so boozed I made advances to someone’s wife, pissed in a bath, & read the opening paragraph of The Wings of the Dove) in June. From the grave - how many miles? Brrr.” – Larkin’s letter to his friend Patsy Murphy, January 1958.

She waited, Kate Croy, for her father to come in, but he kept her unconscionably, and there were moments at which she showed herself, in the glass over the mantel, a face positively pale with the irritation that had brought her to the point of going away without sight of him. It was at this point, however, that she remained; changing her place, moving from the shabby sofa to the armchair upholstered in a glazed cloth that gave at once—she had tried it—the sense of the slippery and of the sticky. She had looked at the sallow prints on the walls and at the lonely magazine, a year old, that combined, with a small lamp in coloured glass and a knitted white centrepiece wanting in freshness, to enhance the effect of the purplish cloth on the principal table; she had above all, from time to time, taken a brief stand on the small balcony to which the pair of long windows gave access. The vulgar little street, in this view, offered scant relief from the vulgar little room; its main office was to suggest to her that the narrow black house-fronts, adjusted to a standard that would have been low even for backs, constituted quite the publicity implied by such privacies. One felt them in the room exactly as one felt the room – the hundred like it or worse – in the street. Each time she turned in again, each time, in her impatience, she gave him up, it was to sound to a deeper depth, while she tasted the faint, flat emanation of things, the failure of fortune and of honour. If she continued to wait it was really, in a manner, that she might not add the shame of fear, of individual, personal collapse, to all the other shames. To feel the street, to feel the room, to feel the tablecloth and the centrepiece and the lamp, gave her a small, salutary sense, at least, of neither shirking nor lying. This whole vision was the worst thing yet – as including, in particular, the interview for which she had prepared herself; and for what had she come but for the worst? She tried to be sad, so as not to be angry; but it made her angry that she couldn’t be sad. And yet where was misery, misery too beaten for blame and chalk-marked by fate like a “lot” at a common auction, if not in these merciless signs of mere mean, stale feelings? – Henry James, The Wings of the Dove (opening paragraph), 1902.

4.

"May God forgive you for the harm you inflicted by endeavouring to restore to reason the most entertaining madman the world has ever known." – Miguel de Cervantes.

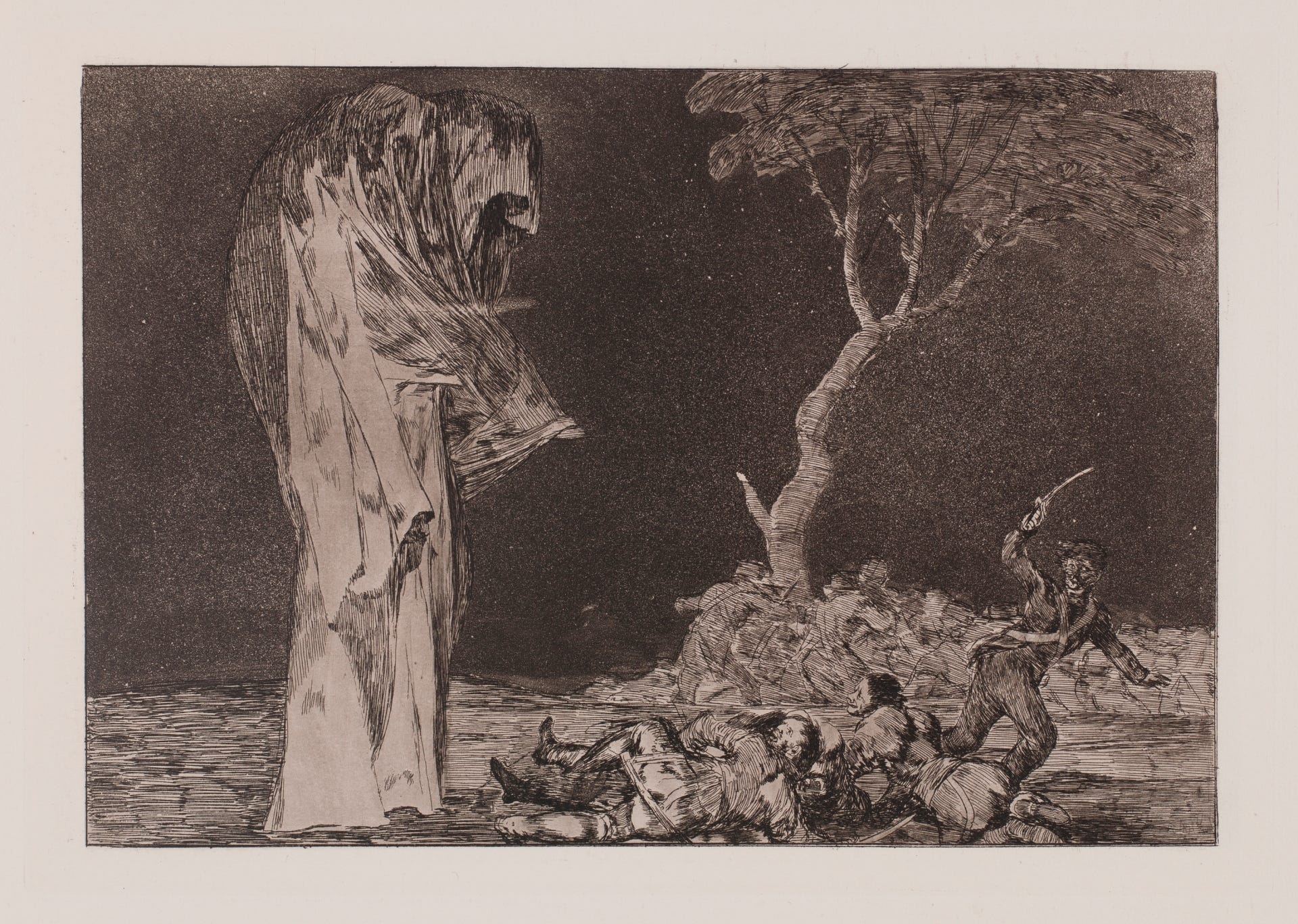

The Christmas before, a consumptive gentleman told him of spirits who become visible through the sheer force of their imagination. Lacking subtlety, they usually choose the most predictable: beautiful virgins, noble knights, mystical druids, old trolls, drunken sailors, lovers astride horses, sad fishermen and suicidal cobblers. Domestic animals are also popular, as are toads1, river fishes, worms, and common garden snails. “But only the debased re-appear in animal forms,” said the wheezy gentleman. “Mostly, we return as what we are, what we know. Men as men, women as women, with the usual number of limbs, but often with fewer orifices.”

He sighed at this point, threw up his arms, and turned into a tree.

That Yule night, Goya read to his son about the cobbler of Breslau who, despite having betrayed God’s will by slitting his own throat, was granted repose in sanctified soil. The desecration did not grant him peace; instead, his tormented spirit arose to haunt the townspeople and, especially, his family, who had sought, in vain, to conceal the grisly truth of his death from the world. Even the poor man’s dog, a loyal companion in life, was so haunted by its master’s visitations that it consumed its tail, and the family had it turned into a clock.

Finally, the grieving widow beseeched the magistrate to exhume her wretched husband’s corpse. Eight months passed, and on the seventh of May, 1592, the grim task was undertaken by the cobbler’s two brothers-in-law who, to their and everyone’s astonishment, found the body uncorrupted. Its form was as pristine as the day it was laid to rest. The self-inflicted wound in its throat gaped but was not putrid, and it had a magical mark – an excrescence in the shape of a rose – on the right big toe.

They removed it from the grave, cut off the head, arms, and legs, opened the back to take out the heart (which was as fresh and whole as a newly killed turkey’s) and burned everything, along with the cadaver’s trunk and shoes, in a giant pyre, until only ashes and femur fragments remained.

The widow swept the remains into a sack and poured them into the river, after which the spectre was never seen again.

Curiously, the cobbler’s maid appeared within eight days after her death to her fellow servant, “laying so heavy upon her as to cause great swelling in her eyes.” The wraith grievously handled a child in the cradle, and if the nurse had not come to its aid, it would have been spoiled. The nurse called upon the name of Jesus, and the spirit vanished. The next night, she appeared as a chicken, which grew into a "vast bigness" and caught a maid by the throat with its beak and talons, leaving her unable to eat or drink for a goodly while. The wraith continued her disturbances for a month, striking some so smartly that passers-by heard the blows. She pulled beds out from under others, threw bricks and stones, and took on different shapes – a woman, a dog, a cat, a toad, an owl, a duck and a black-feathered turkey. But at last, her body was dug up and burned, and the apparition was never seen again.

Once the child was fast slumbering, Goya got out of its bed, went to his worktable, and, in pencil and coal, drew a scene he had witnessed when he was 14: a woman slumped on a stool wearing a blindfold and dunce cap – a capirote – painted with flames and demons. Next to her, he drew an empty candle holder, a symbol of violated faith, and, clutched in her clenched fists, an unlit candle, which probably means something, too.

Behind, a dark mob, barely delineated blobs of black ink, howl for her blood.

Earlier, as she was paraded through the streets, the holy officers, to silence her blasphemies, shoved a cloth in her mouth and beat her with cudgels. They stripped off her clothes and shaved her head. Now, in his depiction, her ankles and toes are tied to her neck, wrists and thumbs. Pulleys link the ropes.

On her sanbenito, across her chest to her crotch, Goya scrawled:

Yo la vi en Zaragoza à Orosia Moreno Por que sabia hacer Ratones

Because she knew how to make mice. Because a neighbour accused her of filling his house with them. Because another said that she had given him a piece of sausage, which turned into a stick.

The other charges against her were soliciting with the devil, lying for money, casting spells, selling fake papal indulgences and having sex with heretics.

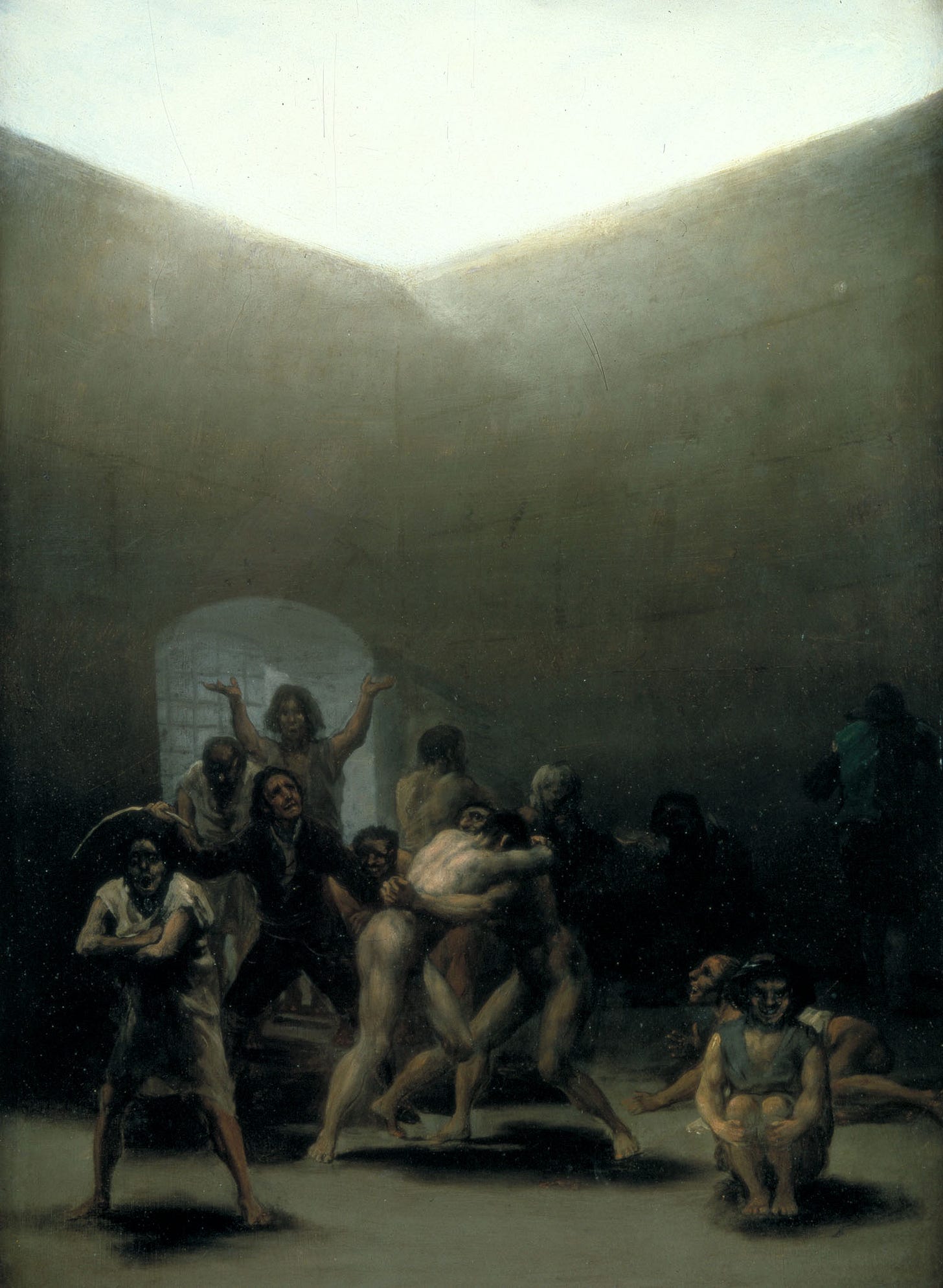

For these crimes, she will be “tormented” for precisely 38 minutes, twisted to the edge of unconsciousness. Then she will renounce. The next day, they will give her 200 lashes and sentence her to life in the madhouse. This is where he thinks he saw her next, straitjacketed in the asylum yard when he visited his incarcerated aunt and uncle there two years later.

Other penitents in Álbum C were accused of other crimes.

Galileo for discovering the movement of the Earth.

Another for having sex with his donkey.

Another for “moving his tongue in a different way.”

Another “For not having legs.”

Another “For being a jew.”

Another “For not having written for fools.”

5.

By now, all’s wrong. In everyone there sleeps

A sense of life lived according to love.

To some it means the difference they could make

By loving others, but across most it sweeps

As all they might have done had they been loved.

That nothing cures. An immense slackening ache,

As when, thawing, the rigid landscape weeps,

Spreads slowly through them – that, and the voice above

Saying Dear child, and all time has disproved.

– Philip Larkin, from "Faith Healing" The Whitsun Weddings, 1960.

6.

Well, I must say, that feels better. Apologies to the trigger-hapless. Thanks for putting up.

Happy holidays, one and all!

Why should I let the toad work

Squat on my life?

Can't I use my wit as a pitchfork

And drive the brute off?

Six days of the week it soils

With its sickening poison -

Just for paying a few bills!

That's out of proportion.

Lots of folk live on their wits:

Lecturers, lispers,

Losels, loblolly-men, louts-

They don't end as paupers;

Lots of folk live up lanes

With fires in a bucket,

Eat windfalls and tinned sardines-

they seem to like it.

Their nippers have got bare feet,

Their unspeakable wives

Are skinny as whippets - and yet

No one actually starves.

Ah, were I courageous enough

To shout Stuff your pension!

But I know, all too well, that's the stuff

That dreams are made on:

For something sufficiently toad-like

Squats in me, too;

Its hunkers are heavy as hard luck,

And cold as snow,

And will never allow me to blarney

My way of getting

The fame and the girl and the money

All at one sitting.

I don't say, one bodies the other

One's spiritual truth;

But I do say it's hard to lose either,

When you have both.

– Philip Larkin, “Toads”, The Less Deceived, 1954.

Thank-you. Cleansing, to read Larkin's pithiness. Goya's world is so absolutely extreme that I shy away.