1.

They look like corpses. Their torsos are covered in scars.

The only illumination comes from two candles on the ground. The men watching crowd out the light. Their shadows hover on the walls.

The rhythms quicken. The women shake. Their mouths are toothless. The men feed them scorpions, jewel beetles, and broken glass. Behind them, little girls dance, their arms crossed above their heads and swaying like wings.

A man cuts off the head of a snake and swallows it. He gives the snake’s still writhing body to one of the women—there are three—and she shakes it above her head, and the blood streams down her scrawny arm. She rubs the snake against her face, utters inarticulate cries, roars like a wild beast and falls to the ground, shuddering, covered in the reptile’s blood.

The legs of the other two women give out and they collapse to the ground still convulsing. The men pull all three by the feet away from the crowd and put pinches of hunting powder in their mouths, which they chew with delight as the men whisper in their ears words whose effect is magical, for the trembling of their bodies diminish, their features unravel, their gaze becomes ecstatic, and they fall asleep.

2.

In 1916, when he was a forty-one-year-old truck driver in the French army, Maurice Ravel sketched out a version of the scene described above in his head, and then in a letter to his mother, Marie Delouart. Twelve years on, it became the principal source of one of his last compositions.

The strange sequence of events described above, which became the genesis of Ravel’s best-known composition—Boléro is said to be played somewhere in the world every fifteen minutes—is believed to be based on a childhood experience: as a 14-year-old, during a visit to the Exposition Universelle of 1889, Ravel saw on the Champs de Mars—just below the brand-new Eiffel Tower—Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov conduct his own compositions, a Javanese gamelan orchestra, a Sudanese string and horn ensemble, gitane bands from Spain, folklorique bands from Russia, Romania, and Serbia, and, on the Esplanade des Invalides, a group of Aïssâoua musicians accompanied by ecstatic Sufi dancers who put poisonous snakes, scorpions and cactus spines in their mouths, stuck spikes into their skulls, tongues, abdomens, genitals and eye sockets, walked on fire, stood on swords, and burned their loins with hot irons.

From then on, Ravel exhibited a taste for the exotic, the macabre and the grotesque. He read obsessively, mainly Symbolist and Decadent dandies and poètes maudits. Among his favourite childhood books was J.K. Huysmans’ A rebours, described by its author as “a very strange novel, vaguely clerical, somewhat pederastic; the novel of the end of a race eaten away by memories of a religious childhood and a malady of the nerves.”

Ravel’s biggest literary influence, however, was Edgar Allan Poe. Like many French artists of his generation,1 Ravel saw in the précieux, ornamented strangeness of Poe, which he discovered through Charles Baudelaire’s translations, an aesthetic standard worth emulating:

I consider sincerity to be the greatest defect in art, because it excludes the possibility of choice. Art is meant to correct nature’s imperfections. Art is a beautiful lie. The most interesting thing in art is to try to overcome difficulties. My teacher in composition was Edgar Poe, because of his analysis of his wonderful poem “The Raven”. Poe taught me that true art is a perfect balance between pure intellect and emotion. My early stage was a reaction against Debussy, against the abandonment of form, of structure, and of architecture. This is, in a few words, the essence of my theories.—interview, ABC de Madrid, 1924

More than anything, Ravel took to heart Poe’s insistence in “The Philosophy of Composition” that “every plot worth the name must be elaborated to its dénouement before anything be attempted with the pen.”

This became Ravel's approach to composition, thinking everything out in his head before setting pen to paper. It presumed an intense mental effort and constant pressure, conscious and unconscious, during the creative act. Poe described his writing of “The Raven” step by step “with the precision and rigid consequences of a mathematical problem.” Ravel liked to tell students, “I do logarithms” to arrive at compositional solutions. Both Poe and Ravel assumed this pseudoscientific posture as a way of disciplining creative frenzy that they feared otherwise might go uncontrolled; the need for discipline in creativity obsessed both men.—Michael Lanford, “Ravel and ‘The Raven’: The Realisation of an Inherited Aesthetic in ‘Boléro’”, The Cambridge Quarterly, September 2011

In 1928, Ravel visited Poe’s boyhood house on Kingsbridge Road in the Bronx. Shortly after, while conducting a Poe-inspired “experiment in a very special and limited direction”, out of his fevered head poured the entire composition of Boléro “in one fell swoop” [“d'un seul coup”].

3.

It was hoped, with reason, that my performances would lead the Arabs to understand that the marabouts' trickery is naught but simple child's play and could not, given its crudeness, be the work of real heavenly emissaries. Naturally, this entailed demonstrating our superiority in everything and showing that, as far as sorcerers are concerned, there is no match for the French.—Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, Confidences d'un prestidigitateur, 1858

Robert-Houdin 's magic shows were scheduled to coincide with a colonial festival honouring Arab chiefs, on evenings of the second and third days of extravagant equestrian games. By the time the magician and his wife reached Algeria, however, armed rebellion had broken out in Kabylia; military operations would postpone his performances for five weeks, until 28 October [1856]. The evening of the first show found Robert-Houdin restless. He recalls anxiously peering out from the wings of the Algiers at the Arab chiefs, with their large entourages, squirming uncomfortably in the unaccustomed seats.—Graham M. Jones, “Modern Magic and the War on Miracles in French Colonial Culture”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, January 2010, Vol. 52, No. 1

Halfway through his performance, Robert-Houdin announced, through a translator, that he would perform his famous “Gun Trick”, in which a member of the audience was invited on stage to shoot him in the heart with a firearm. Instantly, a gigantic marabout, centenarian, wild-eyed, a necromancer’s figure, leapt to his feet. “I will kill you,” he shouted. Robert-Houdin handed him a loaded pistol, which the marabout inspected. “The pistol is in working order,” he responded, “and I will use it to shoot you dead.” Robert-Houdin then instructed him to make a mark with a knife on a lead bullet and load it into the pistol “with a double charge of powder for good measure.”

“Now you're sure that the gun is loaded, and that the bullet will fire?” Robert-Houdin asked. The marabout could not but assent. “Just tell me one thing: do you feel any remorse about killing me in cold blood, even if I authorize it?” By this point, the marabout's response was comically predictable. “No. I want to kill you.” The audience laughed nervously. Robert-Houdin shrugged. Stepping a few yards away, he held up an apple in front of his chest and asked the volunteer to fire right at his heart. Almost immediately, the crack of the pistol rang out. Spectators’ eyes darted from the gun's smoking barrel to the place where Robert-Houdin stood grinning across the stage. The bullet previously marked by the volunteer himself was lodged in the apple, which—the magician reports—the marabout, taking for a powerful talisman, would not give back.—ibid.

4.

On November 4, 1857, my great-grandfather, the socialist activist and dentist Simon Bernard—or, according to some members of the Mooney family, his impostor—walked into a pharmacy in central London and paid cash for a large quantity of mercury and nitric acid. He told the chemist that the chemicals were needed to process daguerreotypes. He produced a sheath of folio-size landscape photographs that he said were examples of his most recent work. He then gave the pharmacist an invitation to a private viewing of his Japanese landscapes. These, he said, had been taken the year before during a three-month posting as official photographer to Townsend Harris, the American consul installed in Japan under the aegis of Commodore Perry. This was four years after Commodore Perry entered Edo harbour with a proud flotilla of American-made cutters, launches, and coal-burning gunboats.

According to the handsomely printed invite, now housed in the Department of Theology archives of the Memorial Library at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the public viewing was to be held the following week in an art gallery in the Mayfair district of London.

He also showed the chemist clippings of two magazine reviews of past exhibitions praising his photographic work. Copies of the articles are also part of the Madison archive. The first, unsigned, appeared in the U.S. journal The Knickerbocker. The following is an excerpt:

We have seen the views taken by Mr. Bernard of the English and Japanese countryside and have no hesitation in avowing that they are the most remarkable of curiosity and admiration, in the arts, that we ever beheld. Their exquisite perfection almost transcends the bounds of sober belief.

The second article, excerpted below, appeared in Sharpe's London Journal and was attributed to Carl Delauney, a noted daguerreotypist and collodion wet-plate photographer:

People are afraid at first to look for any length of time at the pictures Mr. Bernard has produced. They are embarrassed by the clarity of his figures, and believe that the little, tiny faces of the people in his pictures can see out of them, so amazing does the unaccustomed detail and the unaccustomed truth to nature appear to everyone.

The chemist later described Bernard to the authorities as a “red-faced, stumpy man in his late thirties, possibly foreign, though with no discernible accent of speech or costume.”

5.

Ravel was devoted to his mother, a barely literate Basque dressmaker and former smuggler of gitan descent who, like her son, was a “violent atheist” [“athée violente”]: on her deathbed, when called upon by the local priest—she died in 1917, a year after her son sent her the infamous “Aïssâoua” letter, now lost—to pray for her soul, said that she'd rather “be in hell with her family than all alone in heaven.”

His mother was the only great love of his life: Ravel never married, and no official mistress is known. He was assumed, but never proven, to be homosexual; he never had room to love a woman. He had many female friends but never had a relationship with a woman. The musician wrote in 1919: ‘We are not made for marriage, we artists. We are rarely normal and our life is even less normal’ One might suppose that music was sublimation for him, or that he inhibited his sexual drives, turning his impulses into precise and obsessive musical activity. The lack of a nurturing figure weighed on him. — GM Cavallera, S Giudici, L Tommasi. “Shadows and darkness in the brain of a genius: aspects of the neuropsychological literature about the final illness of Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Medical Science Monitor, Oct 2012.

His father, Joseph Ravel, a Swiss engineer, invented two types of two-stroke engines, both of which exploded. Joseph also invented a machine gun and a circular training pool with an artificial current for competitive swimmers. In 1905, he filed a patent for a somersaulting (“loop-de-looping”) vehicle called le Tourbillon de la mort (the “Vortex of Death”). It toured music halls across Europe and the United States until its driver was killed while performing in the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in Cleveland, Ohio. He died in 1908, two years after suffering a brain haemorrhage.

6.

The daguerreotype process does indeed require mercury: the image is produced on a silver plate sensitized by iodine, or iodine and bromine, on which, after exposure in the camera, the latent image is developed by the vapour of mercury. There is, however, no way to determine whether Mr. Bernard, the daguerreotypist mentioned in the two magazine articles, of whom no other textual trace has ever been found, and my great-grandfather, Simon Bernard, the socialist dentist and follower of Karl Marx, were one and the same person. Further, there is no record of an official photographer attached to the diplomatic consul of Townsend Harris. Foreign daguerreotypists were present in Japan at the time of Harris's posting, but none bore resemblance to the red-faced, well-dressed and potentially foreign stumpy customer in the London pharmacy.

7.

In 1914, Ravel tried to enlist in the French Air Force, but was rejected because of his advanced age (39) and poor health—he was a chain smoker with a heart ailment and a hernia who suffered from chronic insomnia and was dangerously underweight. By putting pressure on his friends in the War Cabinet, however, he successfully joined the Thirteenth Artillery Regiment the following year. He hid his enlistment from his mother: her hatred of nationality was as strong as her contempt for religion. And her health was failing, which caused him enormous anxiety and may have exacerbated his own problems: his insomnia had worsened and he suffered digestive problems, for which he underwent a bowel operation, and the winter before he had almost lost both his feet to frostbite. Then, just before his mother’s death, he crashed his munitions truck, which he called Adelaide, while under German mortar fire during the Battle of Verdun.

The accident caused noticeable changes in his mental state. His powers of expression were diminished, but his creative powers grew. He could now hear full compositions in his head and write them down. But soon he was finding it more difficult to speak. Certain motor skills were failing him. By 1927, the year before Boléro, he sometimes couldn’t write his name or distinguish one end of a fork or spoon from the other. But he could still hear and compose music in his head and get it down on paper.

Then, in Paris, on October 8th, 1932, he was hit by a taxi.

8.

His order filled—the chemist found no reason to be suspicious—the vaguely foreign Bernard character left the shop and hurried back to his second-floor flat on Finchley Street, where, once inside, the door securely latched and every article of clothing on his smoothly shaven body removed, he unwrapped his two purchases. These he combined with carefully measured amounts of water and alcohol, producing two litres of mercury fulminate. (Mercury fulminate is a filler for percussion caps. It explodes furiously if shaken or struck hard. Daguerreotypes, on the other hand, require bromine, chlorine fumes and hot mercury. The combination of these chemicals, while highly toxic, is not volatile.)

The explosive mixture was poured—by the Bernard man or an accomplice—into hollow metal spheres custom-built for the purpose by a Brick Lane blacksmith named D.T. Katz. Each container was fitted with a small opening that could be sealed with a screw. No fuse or trigger mechanism was necessary; if hurled at something hard—a wall, a carriage, the ground—the fulminate would detonate, and the metal canister explode, into a far-scattering shower of lethal fragments.

9.

“I love going over factories and seeing vast machinery at work. It is awe-inspiring and great. It was a factory that inspired my Boléro. I would like it always to be played with a vast factory in the background.”—interview, Evening Standard, 1932

Ravel lost two teeth in the taxi accident and suffered a mild concussion. But, after sessions of acupuncture and Japanese massage, he seemed to recover fully. “It was not so serious: chest bruises and some facial cuts.”

Then, while composing a concerto, his hand suddenly stopped writing notes. The musical symbols on the page no longer corresponded to anything in his mind. “I went to the piano: impossible to play.”

Things soon degenerated further. After a recording session of his string quartet, he said to the producer, “That was very good. Remind me of the composer’s name?”

By 1934, he had to consult a dictionary to remember what the letters of the alphabet looked like. By the following year, when he went out to dinner, Mme Reveleau, his devoted housekeeper, had to pin his address inside his coat.

10.

On January 14, 1858, in Paris, four months after Bernard’s visit to the chemist shop in Bethnal Green, Count Felice Orsini and three Italian nationalists—ardent antisemites, all—threw four of these same custom-built metal spheres at the carriage of Napoleon III.

Though the Emperor and Empress were uninjured, eight bystanders were killed and one hundred and forty-eight were wounded. Orsini, struck in the neck by a canister fragment, severed a major artery and narrowly escaped bleeding to death.

After recovering from his injuries, he was guillotined on March 13 before a large crowd on a public square in the centre of the city. There were several illustrators on hand to record the event, as well as three photographers, including Etienne-Jules Marey, the inventor (in 1882, the same year he shot the speech-centre discovery re-enactment: Paul Broca’s autopsy of a speech-impaired patient with a lesion in the third left frontal convolution of the brain) of the photographic rifle, the fusil photographique. It was reported that Orsini faced death with great calmness and bravery.

In London, Simon Bernard, though acquitted of any wrongdoing in the Paris bombing, was committed to the lunatic asylum of Guy’s Hospital. It was reported in the London newspapers at the time that the toxicity of the chemicals he used—both in his photographic and his terrorist activities, resulted in his deteriorated mental condition and, ultimately, in his death, in 1866, at the age of forty-five. Many of his fellows and neighbours, however, maintained that he had been incarcerated because, in the words of Friedrich Engels, who regularly visited and corresponded with the celebrity prisoner, “he knew too much.” It was widely believed, especially among London's left-wing intelligentsia, that the official declaration of incompetency was a sham, meant to keep Bernard silent, out of the public's mind and eye.

Unfortunately, no images exist of Simon Bernard or Felice Orsini. No Bernard photographs have ever been found, though the frontispiece of Orsini’s autobiography, written in English and published in Edinburgh in 1857, features a daguerreotype portrait of the Count.

11.

[Boléro is] the most insolent monstrosity ever perpetuated in the history of music. From the beginning to the end of its 339 measures it is simply the incredible repetition of the same rhythm . . . and above it is the blatant recurrence of an overwhelmingly vulgar cabaret tune that is little removed from the wail of an obstreperous back-alley cat.—Edward Robinson, The Musical Mercury (1932)

On the night of 16 December 1937, Ravel, imprisoned in aphasia and no longer able to do anything but sleep and eat, had, according to Mme Reveleau, who had long been a second mother to him, a sudden moment of lucidity:

Maître startled me by suddenly sitting up in bed, staring straight forward wide-eyed but unseeing and calling for a pen and some manuscript. ‘Napoleon!’ he cried. ‘I see it! I see him! I see her! I hear her! La Loreley!” I tried to calm him, he was shaking violently, I gave him some wine and he settled but only slightly, still babbling wildly and whispering about beautiful virgins and poets and poetry and the Emperor on horseback, Napoleon on horseback, crossing a river. ‘La Lorely’, he repeated, over and over, ‘she’s in the water!’ and more words poured out, and music, Maître began singing, ‘her jewels flashing' and ‘her golden hair’, and other things about magicians and witchcraft, bishops and virgins and widows. ‘Hush,’ I said, and I held his poor head.

It is believed the poets and poetry to have been Heinrich Heine’s “Die Lorelei”2 and Guillaume Apollinaire's “La Loreley”3.

The maître said he was being summoned by God to put these poems to music. And this broke my heart and I made the sign of the cross and he smiled and kissed my face and said, ‘Revel… eau… my love, Marie, my pen, my paper, please, she is still here, she is still waiting for me!’ And I did as he asked, I ran from the room, thinking I should get a priest, and came back with his writing materials, and found him lying back down in his bed, smiling, but the spell had lifted, and he never uttered another word.

The next day, Ravel’s younger brother delivered him to a clinic on rue Boileau, telling him it was just for a test. Instead, a surgeon cut the top of his inadequately anesthetized skull off and injected serum into the left hemisphere of his brain, which was noticeably smaller and slacker than the right. Ravel woke a few hours later, looked around, then closed his eyes forever. Nine days later, he died.

12.

Napoleon's crossing of the Rhine was untroubled by the siren’s song. He slept soundly at Ettlingen. A catnapper, he had a trick:

Different subjects and different affairs are arranged in my head as in a cupboard. When I wish to interrupt one train of thought, I shut that drawer and open another. Do I wish to sleep? I simply close all the drawers and there I am—asleep.

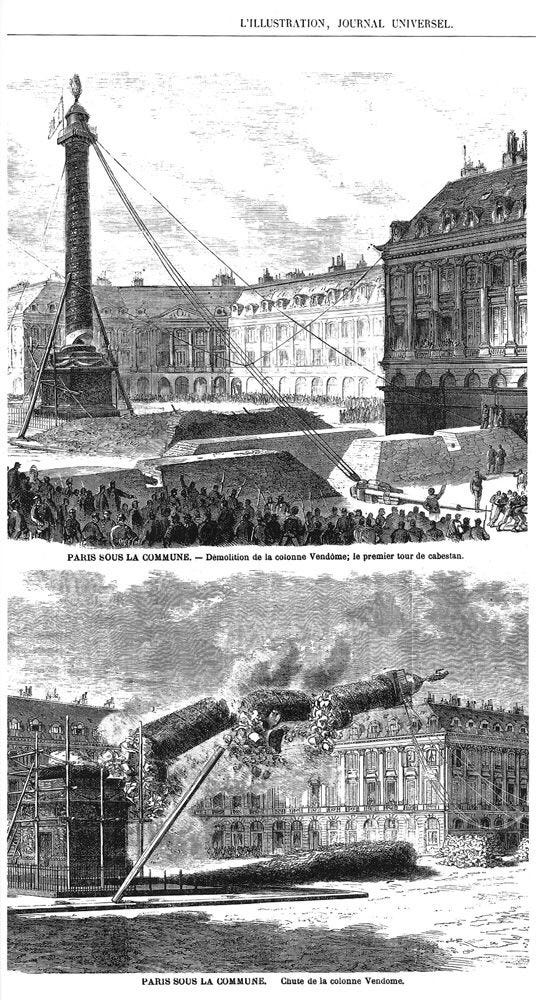

Shut that drawer and open another: C. hates it when I bring up Napoleon but this sleeping trick of his has served me well, and just now jogged a thought that first occurred after the last time we met, after I left you, stumbling out of the Ritz after a hammering night at the Bar Hemingway and looking up at the damn obelisk or whatever it is, the column in the centre of Place Vendôme with the little preening fuck on the top of it. What kind of culture would erect such an absurdity? More to the point, what kind of culture would, once the nasty little man had been deposed, leave the damn thing standing? Courbet and his cohorts pulled it down during the Paris Commune, an image which presents a curious irony: the painter who gave us the world’s most looked-upon cooch4 tearing down the world's biggest prick.

Open another: Courbet drank five liters of wine a day. The painting of his that we admired in the Hermitage, do you remember? Landscape with a Dead Horse. In the center of the forest glade, surrounded by sunlit trees, the bright, white corpse of a horse—legs in the air comme une femme lubrique (Baudelaire)—lying on the edge of the road covered with jewel beetles. In the background, a man clutching a bundle in his hand, running away from the scene. Why is he running? What has happened? Has a crime been committed? What's in the bundle?

Open another: There is nothing in my head but blood and bone. A bloody sponge inside an ossified bucket. Somewhere, Baudelaire has an image of a man dragged to earth by the weight of his wings, unable to walk, barely able to stand. Ravel tried to put this to music but failed.

13.

Flies buzzed on this putrid belly,

From which emerged black battalions

Of larvae, which flowed like a thick liquid

Along its living tatters. – Charles Baudelaire, "La Charogne" ("A Carcass"), 1861 Open another. The insects on Courbet’s horse were, of course, flies, not jewel beetles. Jewel beetles lay their eggs, not on carrion, but in the bark of still-smoldering trees after fires. By means of infrared organs built into their underbellies, they can detect and orient toward a fire from a distance of fifty miles. The adult beetles of both sexes rush in droves toward the flames to take part in a massive coupling frenzy. Once fertilized the females turn their backs on their spent mates and crawl up the sides of the scorched-out trees to lay their eggs in the still-burning bark. The eggs hatch into larvae—white or yellow, legless and blind—that consume the wood, gobble it down, convert it to sugar in their tiny larva bellies.

The broods will only survive in trees recently killed by fire. They pupate either in the bark or tunnel deep into the heartwood.

The adults are fast flyers. They love sunlight and warm temperatures and can be found all over the world, resting on flowers, lolling on wood piles, waiting for the first breath of searing flame to hit their thighs.

Apologies to Anri Sala. I lifted the title of this from his RAVEL RAVEL UNRAVEL installation at the Venice Biennale in 2013. You can read my Art Review piece about it here.

Thanks for reading. Next week, if all goes well, this space will be given over to Zola Mooney, illustrated (with musical accompaniment I hope!) by Otis Jordan. I will leave you now with an excerpt:

THE SOUP

We worked flat land into round land. We grew red. We grew long things, sour smelling and eel-like. Like eels but sticking together like starch. Moving slippery. Squirming in the dirt. We pulled them out by the root (what we call the morble). Muting the squirm with a quick twist of the wrist. All of this that you see, this is the soup. We grow in the soup. We sleep in the soup. We wear hats. All of us childless, all of us growers. We give to the soup and the soup gives back. Sometimes the soup takes away: one day it took away our hearing. We wear hats that cover our ears. We wear a hat like a shell: it covers our heads and parts of our bodies. The stomach but not the back, knees but not elbows. The knees must not be exposed. Exposure of the knees to the soup is fatal. Not much can survive in the soup. Not much can survive the morble fever that the soup puts in your mind and in your body. Only us (rather, the parts of us enclosed), and the long plant. The long plant does not need to wear a hat. It grew out of the fever and so doesn’t need to be protected from it. In fact, it is from the fever that it can survive. Consuming by fevering. All of this happening in cycles of about five to six days. Yes, five or six days after the plant germinates, it has to be killed. We tie a knot with it and wait for it to die. Then we pull it out of the ground. Sometimes it knots itself like a hagfish and there is no work to be done.

(Now you see where I get it from. The tree doesn’t fall from the apple.)

Ravel, from a 1927 interview for The New York Times. “Now, my third teacher was an American, whom we in France were quicker to understand than you [in America]. I speak of the great Edgar Poe, whose aesthetic, indeed, has been extremely close and sympathetic to that of modern French art. Very French is the quality of ‘The Raven’ and much else of his verse, and also his essay on the principles of poetry. “

I will consecrate a future Hexagon to the study of the “Jerry Lewis” phenomenon in France, whereby American artists, especially American writers (Douglas Kennedy, Jonathan Littel, Paul Auster, Jim Harrison, and John (and Dan) Fante come to mind) “lose something in the original” (as Gore Vidal unkindly said of Kurt Vonnegut’s writing) and are held in higher esteem in France than at home, and are even seen, as in the case of Poe, as “French” authors:

T.S. ELIOT: Poe is indeed a stumbling block for the judicial critic. If we examine his work in detail, we seem to find in it nothing but slipshod writing, puerile thinking unsupported by wide reading or profound scholarship, haphazard experiments in various types of writing, chiefly under pressure of financial need, without perfection in any detail… Poe’s influence is equally puzzling. In France the influence of his poetry and of his poetic theories has been immense. In England and America it seems almost negligible. But I am trying to look at him, for a moment, as nearly as I can, through the eyes of three French poets, Baudelaire, Mallarmé and especially Paul Valéry… I think we can trace the development and descent of one particular theory of the nature of poetry through these three poets: and it is a theory which takes its origin in the theory, still more than in the practice, of Edgar Poe. And the impression we get of the influence of Poe is the more impressive, because of the fact that Mallarmé, and Valéry in turn, did not merely derive from Poe through Baudelaire: each of them subjected himself to that influence directly, and has left convincing evidence of the value which he attached to the theory and practice of Poe himself. Now, we all of us like to believe that we understand our own poets better than any foreigner can do; but I think we should be prepared to entertain the possibility that these Frenchmen have seen something in Poe that English-speaking readers have missed.

Here is the Heine:

I don't know what it means,

That I'm so sad,

A fairy tale from ancient times,

I can't get it out of my mind.

The air is cool and it's dark,

And calmly flows the Rhine;

The summit of the mountain sparkles

In the evening sunshine.

The most beautiful virgin sits

Up there wonderfully,

Her golden jewels flashing,

She combs her golden hair

She combs it with a golden comb,

And sings a song as she goes;

That has a wondrous,

A wondrous melody.

The skipper in the little ship

It seizes him with a wild woe;

He looks not at the rocky reefs,

He looks but up on high.

I think the waves will swallow

In the end skipper and barge,

And that’s what, with her singing

The Loreley has done.

(in The Book of Songs, 1827)

Here is the Apollinaire:

In Bacharach there was a blonde witch

Who let all the men around her die of love.

The bishop summoned her to his court

He absolved her in advance because of her beauty

O beautiful Loreley with eyes full of jewels

From what magician do you get your witchcraft?

I'm tired of living and my eyes are cursed

Those who looked at me as a bishop have perished

My eyes are flames, not jewels

Throw this sorcery into the flames

I burn in these flames O beautiful Loreley

Let another condemn you

You have bewitched me

Bishop, you're laughing

Pray to the Virgin for me

Make me die and may God protect you

My lover has gone to a far country

Make me die since I love nothing

My heart hurts me so much

I must die If I looked at myself

I would have to die

My heart hurts so much now that it's gone

My heart hurt so much the day it went away

The bishop sent for three knights with their lances

Take this mad woman to the convent

Go away Lore in madness go away

Lore with trembling eyes

You'll be a nun dressed in black and white

Then the four of them set off down the road

The Loreley implored them, her eyes shining like stars

Knights, let me climb this rock so high

To see my beautiful castle once more

To gaze once more on the river

Then I'll go to the convent of virgins and widows

Up there the wind twisted her unrolled hair

The knights shouted Loreley Loreley

Over there on the Rhine comes a basket

And my lover stands in it he has seen me he calls me

My heart becomes so sweet it's my lover who's coming

She bends over and falls into the Rhine

To have seen in the water the beautiful Loreley

Her eyes the colour of the Rhine, her hair the colour of the sun

(In Alcools, 1913)

Gustave Courbet, L'Origine du monde, 1866