Sensory Overlord

Lines composed after a week alone in the countryside with a universal remote.

Here and there, we hear the kitchens whistling.—This a line from a Baudelaire poem. It is Sunday morning. I’ve had visitors since Friday. One is downstairs in the kitchen, watching a game that was played yesterday. He already knows who wins. This I find odd, but not nearly as odd as what the other friend is doing: standing in the courtyard garden and slapping himself repeatedly—I’m not exactly sure where on his body, probably his arms and legs, but maybe his face and chest—as part of his qigong routine.

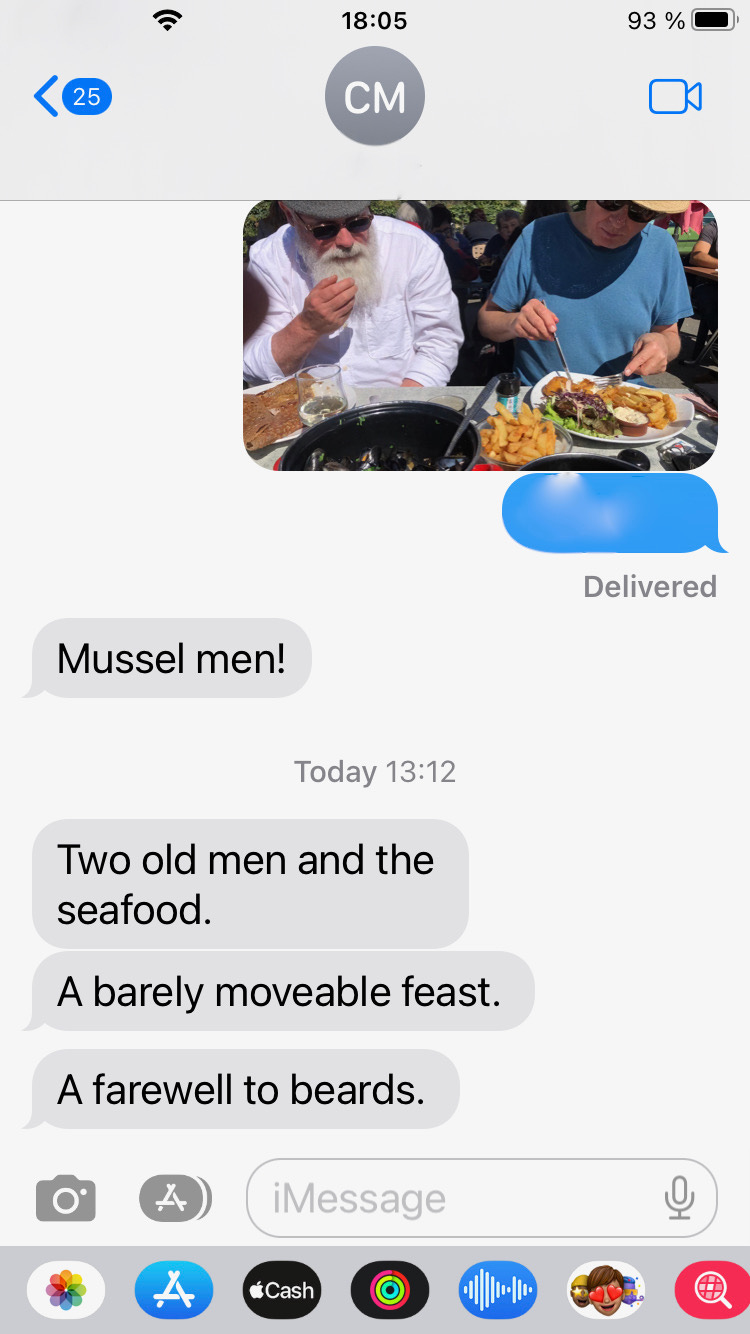

I have a slight hangover. We had wine at lunch on the sunbaked terrasse of the Café du Port in Locquemeau, along with a dozen oysters, moules marinière, a buckwheat galette filled with caramelized apples, sausage and Emmenthal, and the freshest, best-battered fish I think I’ve ever had. I sent this picture to another friend—

-and he texted back—

“Two old men and the seafood” is pretty good.

Anyhow, we finished the meal and went back to the farm and fell into deep naps, and then one friend mowed lawns while the other one pretended to be busy and I made an unnecessary dinner of duck breast and roasted vegetables, with more unnecessary wine, followed by an excessive quantity of superfluous cheese, which required more needless wine, and then some truly unwarranted flan. At the same time we watched, at my insistence, Charlie’s Angels of all things. Because somehow the scene where Sam Rockwell dances was locked in my memory as being truly spectacular, right up there with the scene in Babe that in these pages I once described as “for me, I am not embarrassed to say, the most affective scene in all cinema.”

Doggone it

“Later, the dogs were with their masters, protecting them with loving looks, and later still they were dead, and little stelae sprouted up in the clearing to commemorate love, walks in the sunshine, and shared joy. ” —Michel Houellebecq, The Possibility of an Island

Anyway, the Rockwell scene doesn’t exist or for some reason was clipped from the version we watched last night. The rest of the movie was lame and predictable. My two friends looked at me askance all night. I’m sure they will continue to do so this morning.

I spent the week alone until Friday, working on my Raymond Roussel songspiel. I’ve written the overture and sketched about an hour’s material. I need to take a break to see it fresh, so I’ll quickly knock this out and then go downstairs and start the day. There is coffee, far breton and half a brioche for breakfast. Outside, the thrushes are singing, and the wood cocks are cooing. We will be in the car soon, going to the market in Plestin, then to the beach. The sun is out. It rained all week. I should probably write this piece later—live in the moment, take advantage of the weather and the company. Besides, writing this shouldn’t take long, as the main part will be a short story by my daughter, one of three new pieces, all of which are remarkable, as strange and powerful as the very best short works of Kafka or Musil.

Most of this happens. We buy brandade, herring filets and petites grises, a bad baguette, two lemons and a punnet of Plougastel strawberries. The poissonière gives us a bag of shaved ice to keep everything cold. The caviste sells us an uncorked bottle of chilled Menetou Salon and gives us three plastic cups. We go the Plage des Curés. The picnic tables in the parking lot are filled with people. We walk down the hill to the beach and, to our surprise, find it almost empty. Apparently, people here prefer picnicking in parking lots. I’m also surprised to see that the sand at the edge is covered in what looks like toilet paper. A man with a pitchfork and a plastic bucket tells us that the toilet paper is actually dried-out algae deposited a month ago by a high “green tide”. Not the green algae that kill, we ask. Yes, he says, the same. Sea lettuce. We’ve read about this. Fertilisers and phosphorus carried by rivers to the sea. Not dangerous to humans, we’re told by the “public authorities”. Pitchfork guy disagrees, as do many people in Brittany. When they decompose, green algae release toxic ammonia and hydrogen sulphide fumes, which is why, in bays like this, thick layers deposited by high green tides are usually collected as soon as they appear. But somehow, this green tidal dump was missed.

What’s in the bucket, we ask. Sandworms, he says. For fishing. Cousins of earthworms but these live in sand. We look in the bucket. The worms are curling and uncurling vigorously. Ils bougent bien, we say. Nothing better for fishing, he says.

Worms. Remember that thunder only happening when it’s raining nonsense? It’s finally gone. As is the Stevie Wonder and Neil Diamond songs that replaced it. Worms are still there, however, but instead of plaguing my ears, they are now in my eyes — eyeworms—looping rom-com trailers brought forth by a week’s tedious trawling on Amazon Prime, now coiled intestinally around my brain, cutting off circulation to my soul.

Collect yourself, my soul, in this grave moment / and close your ear to this roar. It is the hour when the pains of the sick become bitter! These are line in the same Baudelaire poem. My soul, yours, Baudelaire’s, does it matter? The lead characters are the same. So are the sidekicks. The dotty parents. The adorable pets. See these and absorb them, but your chief focus should be the potted plants on the bookshelves. The kitchen cupboards. The curtains swaying in the autumn breeze. These might still send messages.

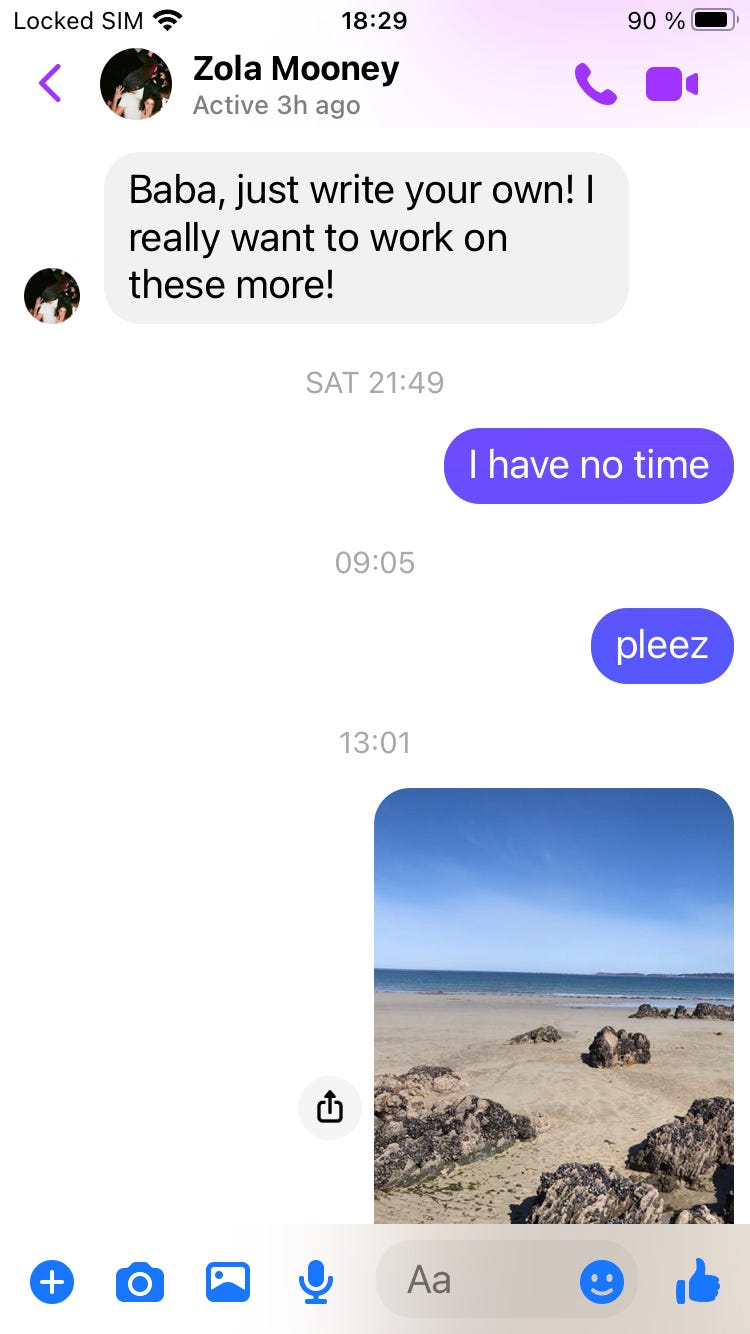

Further out, we see two children with their mother hunting for shrimp in the tidal pools. And after our cold, cold swim, while we eat the shrimp and fish we brought and drink the delicious wine, I get a text from my daughter—

And then, crickets. So that’s that. No extraordinary short story from Zola Mooney. Just this blank space, spread out like the cloudless sky above my head. Thankfully, we abound in choice. I hear the mower again, and Bach on the harpsichord. Dinner is being prepared downstairs. Films are being selected. I use the passive because I am not involved with these activities, as I am writing this. For you. And for myself. Are you following the situations? Outside, behind all this curtain swaying, nothing is likely to be urgent. So I’ll get back to real work tomorrow, and go for a long run down a country road or along a coastal path, and maybe drop starches and sugars entirely. In the meantime, let me close with a recent poem by Zola Mooney and a plug for her man Otis Jordan’s excellent new album Net of Atoms. His large-ensemble tour kicks off at the end of the month with the following concerts:

26/09 - Settlement Projects, Leith Walk, Edinburgh (with Tinnman & Cod O’Donnell)

27/09 - McNeills, Glasgow (with The Universal Veil)

28/09 - Nan Moor’s, Todmorden (with Rotter Otter - Matinee Show)

29/09 - The Talleyrand, Manchester (with The Universal Veil & Ike Goldman)

And now, without further ado:

LAS AGNE, by Zola Mooney

To put away the dishes with wet hands.

With wet hands: draw dinner,

Make shapes in ground beef,

Cut through the continuous sounding

Like through cold meat.

A little too loudly, my neighbours are painting the walls, alternating red and white. Don’t they

look glum from my window, faces in limp grimace, musculature growing glutinous.

I have eyes like plain white walls, operating, on several planes, several separations at once.

The eye doctor says that I must spend ten seconds staring at a point in the distance every

half hour. Otherwise the sheets become confused, sticking together as they boil, unoiled,

unevenly covered.

I begin to think: will this structure hold?

Can this shallow dish contain such richness,

And horror,

And textures, so different one from the other,

As I continue, grimacing, to slop

More and more on top,

Making me ill with oil, and

In need of meatless and calm. We could all use some meatless and calm, no?

Man, that was quite the blast.

Yes. This stuff. Keep it up!