Hand jobs

"Culture appears to us first of all as the knowledge of what made us something other than an accident of the universe." André Malraux

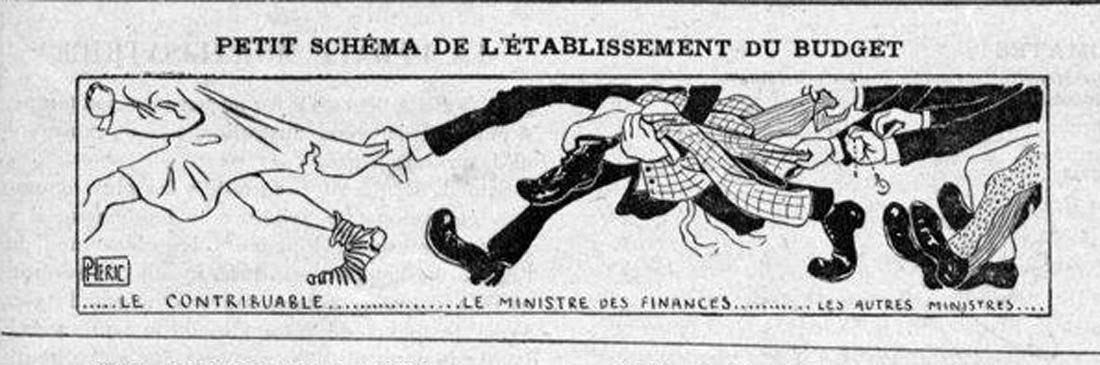

In an interview in Le Monde in 1992, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu described the modern state as an ambidextrous animal that, with its left hand, the “so-called spending ministries” – in charge of crèches, schools, universities, social services, hospitals, courts of justice and publicly supported “cultural industries” such as television, radio, cinema, theatres, museums and libraries – tries to hold society together and make it fit to live in. Meanwhile, its right hand, “the énarques1 of the Ministry of Finance, the public or private banks and the ministerial cabinets”, holds society upside down and shake profits out of its pockets. Or its mouth:

Locked in the narrow and short-sighted economism of the IMF-worldview that also wreaks havoc on North-South relations, all these half-skilled economists obviously fail to consider the real short-term, and especially long-term, costs of the material and moral misery that is the only certain consequence of economically legitimised realpolitik: delinquency, crime, alcoholism, traffic accidents, etc. Here again, the right hand, obsessed with the question of financial balances, ignores what the left hand does, confronted with the often very costly social consequences of “budgetary savings”… Many of the social movements we are witnessing (and will witness) express the revolt of the small nobility of the State against the great nobility of the State.

In November 2015, two days after the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris and Saint-Denis, a group of French theatre directors revisited Bourdieu’s double-handed concept in an open letter in Le Monde:

If we want to reinvent society, if we want to give a chance to France "after [the attacks]”, we must reclaim public spaces. Secular and free spaces, protected from the violent pressure of private interests, whether religious or economic. Spaces in which to unfold narratives and develop imaginations. Spaces in which to elaborate the hope of a habitable world. This is an urgent struggle, and it is a political struggle…

And what we say here about this novelty of the theatre, because we love it and defend it, because it is our vocation and mission, is also true for the other arts [and] everything that Pierre Bourdieu, in Misery of the World, called “the left hand of the state”: all those public services that create social cohesion, that seek to make it liveable and not simply profitable. For too long in our country, a summary and very ideological discourse has tried to disqualify these public services by making them responsible for all the evils and all the failures. To such an extent that the people and institutions that embody them have had as their only perspectives over the last few decades the reduction of budgets and staff, “rationalization” and “restructuring”. So much so that the very word "public,” so essential to us as men and women of the theatre, has come to be seen as an insult, because of the identification of all that it covers with “expenses” (the famous “public expenses”) that are necessarily “excessive” and “inefficient”. The damage caused by this narrow conception of politics and society cannot be denounced enough. We continue to suffer the effects.

What was true in 1993 and 2015 is, of course, just as true in 2023, only more so. And nowhere more so than in France, where examples of “economically legitimised realpolitik” are a dime a dozen.

The “small nobility of the State”, responding to the right-handers’ violent and autocratic imposition of two more years of late-life drudgery, are indeed in pleine révolte, getting their heads bashed in shoulder to shoulder with the working classes, and now not even allowed to bang a pot.

Funding throughout the social body is focussed obsessively on pecuniary return. Hospitals are under-financed, universities are all business, prisons are purely for profit.

Money doesn’t just talk, it screeches, purrs, whines, bitches and bleats. As P.J. O’Rourke, author of “How to Drive Fast on Drugs While Getting Your Wing-Wang Squeezed and Not Spill Your Drink” put it, way back in politically uncorrected 1979, “you shouldn’t stick your nose in other people’s business, except to make a buck.” Amusing then; today it accurately sums up the characteristic customs and conventions of most of our “transactionalities”. Life has become one big game of Texas hold 'em. And we’re all in. And we’re all bluffing.

But forget 1979, 1992, 2015 and 2023, and travel back with me to 1958, to the 19th of May press conference of General de Gaulle in the hotel ballroom of the Gare d’Orsay.

Five days before, French paratroopers, sent by the rebel officers behind the military coup d'état in Algeria, flew from Algiers to Corsica and took control of the island. The mini-putsch was bloodless and symbolic: 15 years before, Corsica had been the first French department liberated from the Nazis.

Once in position, the putschistes demanded that General de Gaulle be returned to power. If he wasn’t, they warned, parachutists and armoured forces based in Rambouillet, just outside Paris, would attack the French Assembly.

The government immediately resigned. President Rene Coty appointed de Gaulle Prime Minister, with a mandate to dismantle the Fourth Republic.

Now zero in on the moment when, after announcing that he was “ready to assume the powers of the Republic”, and promising to not inviolate civil liberties (and please watch this hilarious video of de Gaulle doing stand-up à la Louis de Funes) –

Have I ever done that? Quite the opposite, I have re-established them when they had disappeared. Who honestly believes that, at age 67, I would start a career as a dictator?

– the general shook the hand of André Malraux, who had served as his Minister of Information in his first government in 1945. Recently renamed to that position, one of the first bits of info Malraux shared with the world was that the French were using torture in Algeria. Not only that: he promised that as President de Gaulle would put an end to it. De Gaulle, horrified, decided his spokesperson needed to be reassigned. He turned to Michel Debré, the new Prime Minister, and said, “It will be useful for you to keep Malraux. Carve out a ministry for him, for example, a grouping of services that you can call ‘Cultural Affairs’. Malraux will give relief to your government. Only he is capable of giving the tone and grandeur that is needed. He epitomises the French genius of panache.”

Thus was born the first French Ministry of Culture.

“I make things up, but the world is beginning to resemble my fabrications.” – André Malraux.

No other homme politique has a resumé quite like André Malraux’s. One of the last monstres sacrés of French literature – after Camus, he is the country’s best-selling writer – his literary success was in part based on his reputation as a man of action, a hybrid of T.E. and D.H. Lawrence: erudite art critic, anti-colonial adventurer, squadron leader in the Spanish Civil war, decorated résistant, and a con artist who forged his wartime records, inventing gunshot wounds and writing that he had been “tortured” – which was true, but not by the Germans. By his shoes, which were too small for his feet.

“One third genius, one third fraud, one third incomprehensible,” said Raymond Aron, his chief of staff at the Ministry of Information in 1945. Among his CV’s “embellishments”: doctor of letters (he dropped out of school at 17, before receiving his bac); student of oriental languages who read Sanskrit, Persian and ancient Greek; people's commissioner in China; member of the Central Committee of the Kuomintang; and friend and confidante of Mao Tse-tung and Zhou Enlai.

As they say: n’importe quoi.

He sold fake Picassos to finance his Tintin-like escapades, which included a trek through the Yemeni dessert to find the lost realm of Queen Sheba, and a tomb-raiding expedition in Cambodia, where he sawed Khmer bas-reliefs off temple walls, for which he went to prison.

He never met Stalin in Moscow or Goebbels in Berlin, as he liked to tell people. But he did meet and admire Trotsky in 1922. He told Richard Nixon, who asked Malraux to brief him before his China trip, that he had “known Mao Tse-tung and Zhou Enlai in China in 1930” and that he “kept in touch with them intermittently over the years.” This wasn’t true, though in Beijing, in 1965, he had a very brief audience with Zhou, who said nothing, and Mao, who offered a few platitudes.

Nixon's advisors had differing opinions on Malraux's performance. Leonard Garment found Malraux “fascinating because he had a fascinating story”. John Scali, on the other hand, said he was not impressed by Malraux's ‘musings’, which were muddled, contradictory, and riddled with oversights or illogicalities; Malraux was, for Scali, “a pretentious old man weaving obsolete ideas into a special framework for the world as he would have wanted it to be.” Henry Kissinger, in his memoirs published in 1979, deplored the fact that Malraux's knowledge of China was very backward and his short-term predictions "outrageously wrong.” – Wikipedia

A fellow traveller before the war, he became a vehement anti-communist after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. However, already deeply under the spell of gaullisme, he had long before abandoned his comrades on the left. From 1958 to 1969, despite his opposition to the Algerian war, he loyally served as the General’s sycophantic house intellectual and goodwill ambassador.

Ravaged by alcohol, antidepressants, tranquillisers, neuroleptics and sleeping pills, his erudition became mystical and perplexing, and his self-aggrandising myth-making thicker and hollower. Nominated and rejected by the Nobel committee more than 30 times, he has since all but disappeared from bookshelves – La Condition Humaine (Man’s Fate), which won the Prix Goncourt in 1933, is his only work still in wide circulation – and, though pantheonised by Chirac in 1996, he would probably be forgotten today were it not for what he did for – or depending on your point of view, to – French culture.

Briefly put: he reorganised the country’s theatre system, turning the national theatres into public establishments, splitting the Odéon off from the Comédie Française and creating a third, the Théâtre de France, and putting his friend Jean-Louis Barrault in charge of it. Barrault would later fall out with Malraux because of his support of the Mai 68 demonstrations, but not before premiering plays by Ionesco, Beckett, Duras, Claudel and Genet, including Genet’s Les Paravents (The Screens). Created just after the end of the Algerian war, every performance of The Screens was violently disrupted by extreme right militants, who, along with most of the right wing in parliament, called for its banning, which Malraux eloquently opposed on the floor of the Assemblée Nationale.

He ended Paris’s monopoly on the exhibition and creation of art by opening Maisons de la Culture across the country. These “modern cathedrals… make the capital works of humanity accessible to the greatest number of French people… Here any 16-year-old child, however poor, can have a real contact with their national heritage and with the glory of the spirit of humanity.”

He gave subsidies to theatre and dance troupes, both public and private. He did the same for publishers and bookstores, and film producers and distributors. He broadened unemployment benefits for artists, performers, filmmakers, and technicians, extended social security to writers, created the Centre National d'Art Contemporain (which was later integrated into the Centre Pompidou), founded the Biennale de Paris, rebuilt the Château de Versailles, wrote laws regulating the restoration and protection of historical monuments and sites across France, established a national musical policy, revamped and revitalised the music conservatory program, changed the way architecture was taught, commissioned major public works by Braque, Picasso and Giacometti, and created a general inventory of French artistic patrimoine.

Not bad for a lying lush who popped pills like candy and took a hacksaw to buddhas in Angor Wat.

This, as usual, is getting long in the mouth, so I’ll stop here, and weigh in later on the cultural consequences of the “Malrucian” era. On whether public subsidies for the arts supports or stymies creation, nourishes the exceptional or coddles the conforming, protects artists or turns them into servile bureaucrats. Can art be democratised? Can culture be produced by budgetary means? Etcetera. I’d love to hear your thoughts on it. But right now it’s time to hit send, get dressed and celebrate.

Celebrate what? Hexagon’s first birthday, that’s what! Talk about an “accident of the universe”: one year (and 41 posts) old and still mewling away and toddling along, thanks to neither the left nor the right hand of the state but to my beloved subscribers, without whom I would have had to throw this baby out long ago, and re-submerge my entire being and budget in the dingy bathwater of hired hackism. To those who have supported this endeavour, whether by kicking in a few bucks or just by reading this far, thank you. I am in your debt, and will raise a glass to you this afternoon at Chambre Noire’s 4th annual German wine-tasting at Le Consular. If you’re in Paris, pop by.

Otherwise, bis zur nächsten Woche!

Graduates of the École nationale d'administration (ENA), the “Grand Ecole” where was most senior civil servants of the French state were selected and trained. Created in 1945, it was replaced by the Institut national du service public (INSP) in 2022.

Love the line

“ Life has become one big game of Texas hold 'em. And we’re all in. And we’re all bluffing.”

Top shelf musings, right up where mom keeps the beurre d’arachide.