This is War Too: Picasso, Duchamp, Trump & Volume-Control

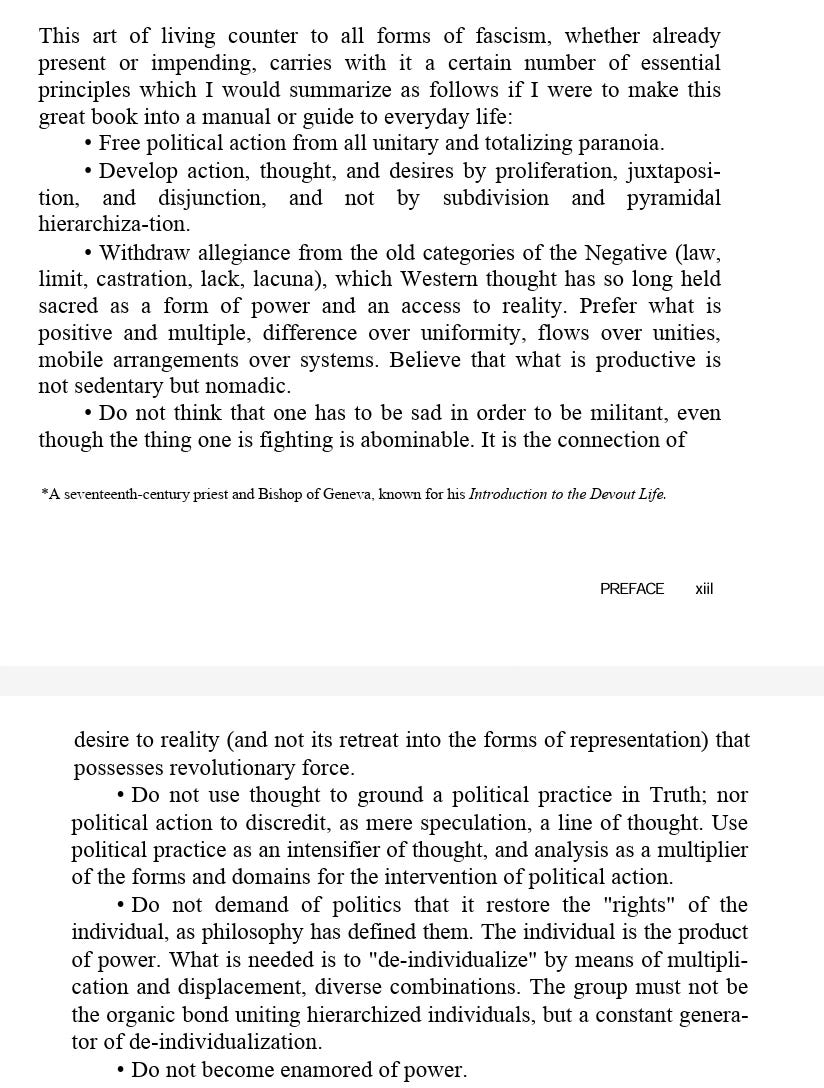

"Don't fall in love with power." – MF, 1977

You push the button, we do the rest. – George Eastman, 1888.

VLADIMIR: Moron! ESTRAGON: Vermin! VLADIMIR: Abortion! ESTRAGON: Morpion! VLADIMIR: Sewer-rat! ESTRAGON: Curate! VLADIMIR: Cretin!

– Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot, 1948-49.

In early 1940, after the death of his mother and his return to Paris from Royan, Pablo Picasso secretly applied for French nationality. He had every reason to believe the request would be granted: he had lived in France since 1900 and, next to Matisse, was by 1940 the best-known artist in the country; he had never been charged with a crime (despite his arrest for the theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911); and he had paid taxes every year since 1916, the year income tax was introduced in France (in 1939, he coughed up a whopping 700,000 francs – 1,211,720 euros in today’s money). However, for reasons never officially stated, the request was denied. In his police dossier, which resurfaced in a cache of KGB files in Moscow in 2003, an officer wrote: “He is without qualifications to obtain naturalisation; moreover, given the foregoing, he must be considered extremely suspicious from the national point of view.” The “foregoing” were entries in the file dating back to 1901: “alien suspect”; “anarchist monitored by the prefecture”; “so-called ‘modern’ painter”; proponent of “incomprehensible art”; “30 years old in 1914 but did nothing for our country during the war”; “speaks French very badly, and can barely make himself understood”; “has made millions (most of it said to be in foreign bank accounts)”; “Soviet apologist”; “has prints in his studio representing the hammer and sickle”, and, the kicker, an anonymous denunciation made just before the Nazis crossed into France: “has expressed anti-French sentiments.”

The anonymous denunciation. Settling scores. Currying favour, making a buck, getting ahead, or simply surviving. “Délation”, as it is known in French, always something of a national pastime in France, was especially popular during the Occupation. Between 1940 and 1944, Frenchmen and women sent between three and five million denunciation letters. The usual motivations were in play: xenophobia, ideology, hatred, self-interest, malice – and combinations thereof. Jews, foreigners, communists, homosexuals, refugees – the usual suspects were targetted, and, as always, moral compromises and contortions were the consequences. People hid their thoughts. Censored their words. Were suspicious of their neighbours. Locked their doors. Turned down their radios.1 Kept their curtains drawn. Spoke in whispers. Feared the police, the Gestapo, their co-workers. Their own families. Themselves.

Sound familiar? In rooms around the world. Down the passages we go, towards the doors we may soon have to open. These footfalls still echo in our collective memory – of choices made and unmade, of complicity and resistance – spectral presences in our collective consciousness, reminders of what there is to lose, and how quickly civilisations crack from fear.

2.

The world tells its own tale and, in its general decadence, bears adequate witness that it is approaching its end. There is less innocence in the courts, less justice in the judges, less concord between friends, less artistic sincerity, less moral strictness. – Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, 250 AD.

You hate him? That’s fine. He’s hateable, nothing if not, and despite what people will tell you, there’s nothing wrong with hating a person – as long as doing so doesn’t make you miserable, or mean, or shitty to your friends and family, or to random people on the street, or entire races or genders or nations or classes, or small animals, just as there is nothing wrong with hating small animals, or snakes, or Tom Cruise, or Star Wars, or traffic jams or philosophy. Or, for that matter, an iceberg, like the famous one in the photograph above, which was a mile long when it cracked free from Greenland sometime in the spring of 1911, but by the time the Titanic’s starboard hull scraped against it on the night of April 14-15, 1912, just 30 seconds after those on board first spotted it – and just hours before, we are told, Picasso, in Céret, started Violon et Raisins, which we will get to in a minute – it had melted down to just under 400 feet, roughly the size of an American football field.

How much of it, however, was submerged and unseen will forever remain unknowable.2

And that is the main difference between Trump and the Titanic iceberg.

But go ahead, throw yourself into hate body and soul. Hate’em both. Snakes too. Because, never forget, hate can be productive. Baudelaire called it a precious liquid, a poison dearer than that of the Borgias because it is made from our blood, our health, our sleep, and two-thirds of our love – but we must be stingy with it. It makes the sun cross the sky. But when the sun goes down, who tends the fire, lights the night, keeps the ice and darkness at bay? Are these even the right questions? We asked tougher ones before the tech bros top-loaded our skulls. We need to ask them again. For example, what is he to you?

More to the point, what am I to you? We know each other, sure, or at least of each other, or so we like to think, and we also know that that thought and every other thought, including this thought, follows a specific pattern. The memory of a thought, however, is not contained within its pattern. The pattern is the memory. Does that make sense? Who we are, what we imagine, how we focus and plan, what moves us now, what moved us then – penetrates our skin and is held in our blood, and we carry this with us, these things, these thoughts; they become our history, the track marks on our paths and arms that shape the decisions and emotions that form the base upon which everything we do and say and feel and think is structured – even if our unconscious brain processes determine many of those decisions and emotions long before we are consciously aware of them. Even if it turns out that there is no such thing as free will and we have no conscious control over our actions, the outcome is the same, we are confined within its panoptical purview, at once its architect, warden, and prisoner.

Nonsense, right? Just like history, so-called history, which, as Henry Ford once said, is more or less bunk. This was in 1916, just before he about-faced from pacifist to war profiteer. “It's tradition. We don't want tradition. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history that we make today.”

Tradition, the customary way of doing things, the burden of all those “dead generations that weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living”3 – into the dustbin with it. So say his DOGE bodies. History for them is a fully automatic weapon, a round-the-clock Glock chambering and firing continuously, feeding and ignition procedures ceaselessly cycling – no need to reload, just keep a finger on the trigger and bullets in the belt. Meaning you no longer have to worry about whether it’s a tragedy or a farce, and you no longer have to forget something to remember it. But how can you search for something when you don't know what it is? How do you recognise something you've never encountered?

Ok, yes, a bit portentous – more than a bit. And off the mark, neither here nor there. Apologies. My head, examined: should I have? I realise I am overstepping. I know I should follow protocol and respect the intervening layers. But this is not the time for consensus building. At a certain point, you have to trim the bit and adjust the bridle, saddle up, and leave the ranch. Baudelaire said that the Devil’s most cunning trick is to persuade you that he does not exist. This is no longer true. He does not hide. He is here, in plain sight. Hate him all you want.

Sate your hate.

Knock yourself out.

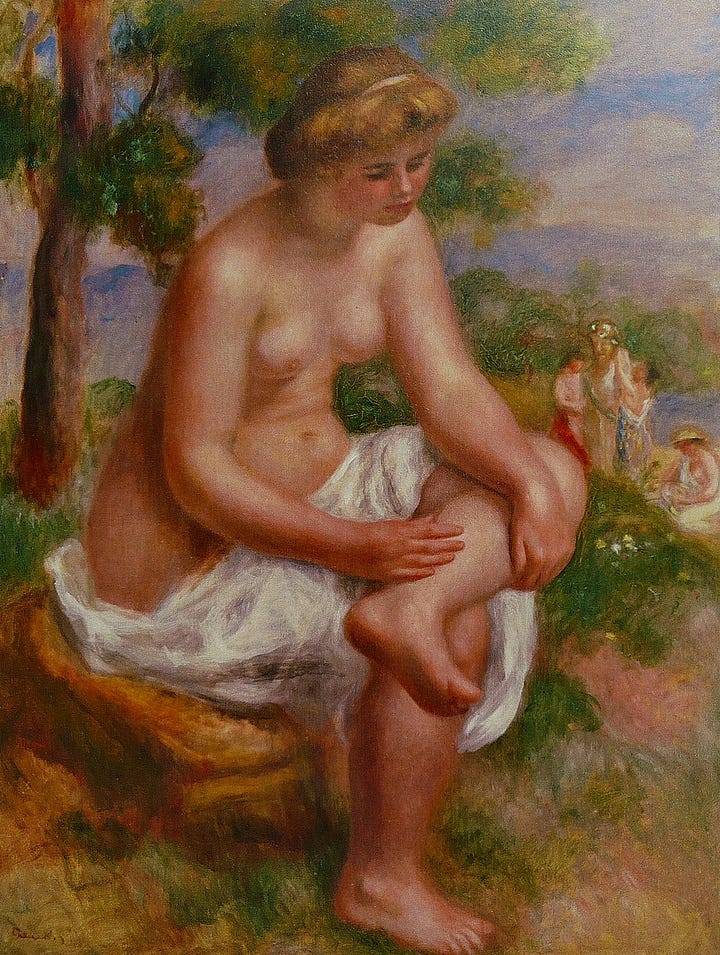

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Baigneuse assise dans un paysage, dite Eurydice, 1895-1900 (purchasd by Picasso in the early 1920s).

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Les Deux Sœurs,1881 (the god-awful original in The Art Institute of Chicago, not the even-worse forgery on Trump Force One).

3.

Eryxias: Does the private exist?

Erasistratus: No.

Eryxias: Everything is public?

Erasistratus: Yes.

Eryxias: Ok, with that in mind, I’d like to start today’s proceedings with a potted history.

Erasistratus: Are not all histories “potted”?

– Plato, Erasistratus.Instead of offering Picasso citizenship, the authorities sent the police around to trash a few paintings and take all his bed linen. They had already listed him as a “degenerate”4 and prohibited the sale of his works, books and reproductions. He was not allowed to exhibit. In 1942, to renew his French residency permit, he had to sign an affidavit declaring: “I, the undersigned, declare on my honour that I am not Jewish”. At the 1943 Salon d’Automne in the Palais de Tokyo, where his old friend Georges Braque was given a full retrospective – 26 paintings and 9 sculptures – he was not even allowed to attend the vernissage.

Not that he would have. Though, as we mentioned last time, he often lunched with devils, he refused favours from Vichy officialdom and the occupiers. According to one apocryphal story, first told in the pages of American Vogue in January 1943, Otto Abetz, the German Ambassador, after offering him firewood (to which Picasso replied, “A Spaniard is never cold”), followed by butter, sugar, chocolate, and cigarettes – which Picasso also declined – turned to a postcard of Guernica and said, “Did you do that?”

Picasso allegedly replied, “No, you did.”

A week before the 1943 Salon’s opening, Picasso’s visa was revoked, and the German Employment Office summoned him to report for fitness tests to determine whether he was healthy enough to survive deportation and forced labour in Germany. “Any failure to comply will be punished mercilessly.”

4.

A Picasso studies an object the way a surgeon dissects a corpse. – Apollinaire, 1912.

The thing about Picasso, the young, fit Picasso, the one Apollinaire is writing about in 1912, the Picasso still under the thrall of Cézanne’s cylinders, cones and spheres, is that he knew his audience knew what a fucking violin was – and what a cluster of grapes looked like, and a guitar or a bottle, a bull or a torso or a head – and that at least some of the people in that audience didn’t need or want him to just keep rendering and explaining violins and guitars and grapes, make them just beautiful, decorative, or childlike, or photolike, or painterly, or mindlessly faithful to the simple terms of their most basic information.

Violins, grapes, torsos, heads, skulls, bulls, clowns – and monsters, too – but other than the odd beach in a background, next to no landscapes, as far as the eye can see. “I never saw one. I’ve always lived inside myself.” In this sense, he shared something with his beloved Rimbaud: “It is false to say, I think. One should say: I am thought. Pardon the wordplay. I is another (“Je est un autre”). Too bad for the wood that finds itself a violin, and to hell to the heedless who argue over what they know nothing about!” He also shared something with his loathed Duchamp. Not Duchamp’s distaste for the merely seen, as opposed to the more heroically thought. Picasso remained retinal and plastic his entire life - “bête comme un peintre” in Duchamp’s estimation, “as stupid as a painter”, entirely focused on visual experiences and sensuous pleasure (Picasso: “I would love to paint like a blind man, who pictures an arse by the way it feels”)5. Duchamp was a snoot, an intellectual ascetic pedant who peered at the world through the peepholes in his door6, and he had Picasso way up his arse and in his mind when he said, “The majority of artists, let's face it, are very skilled brutes, mere manual labourers, village pub-talkers with the minds of country bumpkins.” But both were game players and game changers, and like many of their contemporaries, they broke with the milieu juste7 compromises and the cheesy style pompier8 conformities officially championed in the arts in France during the Third Republic, under Vichy and the Nazis, and under the Gaullists that followed.

But before the war and during it, what did they do? What should they have done? What would you have done? What are you doing right now?

Speaking of cheese. In early 1941, during the same cold snap that had Picasso huddled next to Gertrude Stein’s electric heater in his studio’s bathroom, writing Desire Caught by the Tail/Prick (see last week’s Hexagon), Duchamp finally decided to abandon his cat and leave Grenoble for America. It would take him a year to secure a visa. To prepare, that spring, he called upon an old friend, Gustave Candel, a négociant en fromage at Les Halles (for whom he painted portraits of his parents in 1912, when he and Gustave were neighbours in Montmartre, and the Titanic was heading out on its maiden voyage9) to get him a Nazi-issued Ausweis. The pass allowed him to travel in and out of Free France posing as a cheese merchant with a salesman’s display suitcase containing secret compartments for his miniaturised artworks – les “pièces detachees” – of his first Boîte-en-valise.

Between 1941 and 1966, Duchamp created 312 more Boîte-en-valises, including 22 deluxe “Series A” editions. In 2021, Christie’s sold the “Series A” edition above for 2,070,00 USD. In 2018, it sold a “Series F” (the least deluxe) for 211,500 euros.

5.

“Change your thoughts, and you change your world.” – The Reverend Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, 33°, The Power of Positive Thinking”, 1952

In another interview in Vogue, in 1963, between Marcel Duchamp and the MoMa’s William Seitz, Duchamp described painting as “only a tool, a bridge to somewhere else” and then went on to say, somewhat obliquely, that “the famous ‘to be’ is consciousness, and when you sleep you ‘are’ no more. That's what I mean – a state of sleepingness; because consciousness is a formulation, a very gratuitous formulation of something, but nothing else. And I go further by saying that words such as truth, art, veracity, or anything are stupid in themselves. Of course, it's difficult to formulate, so I insist that every word I am telling you now is stupid and wrong.”

Seitz, trying to make sense of this, asked, “Could it be otherwise? Can you conceive of finding words which would be appropriate?” Duchamp thought about this, pondered it like a chess move, and replied:

“No. Because words are the tools of ‘to be’ – of expression. They are completely built on the fact that you ‘are’ and in order to express it you have built a little alphabet and you make your words from it. So it's a vicious circle. I mean it's completely idiotic. I mean the language is a great enemy, in the first place. The language and thinking in words are the great enemies of man, if man exists. And even if he doesn’t...”

The interviewer changed the subject.

6.

“Why do you think I date everything I do? Because it is not sufficient to know an artist's works – it is also necessary to know when he did them, why, how, under what circumstances.” – Picasso, in conversation with Brassai, 1943.

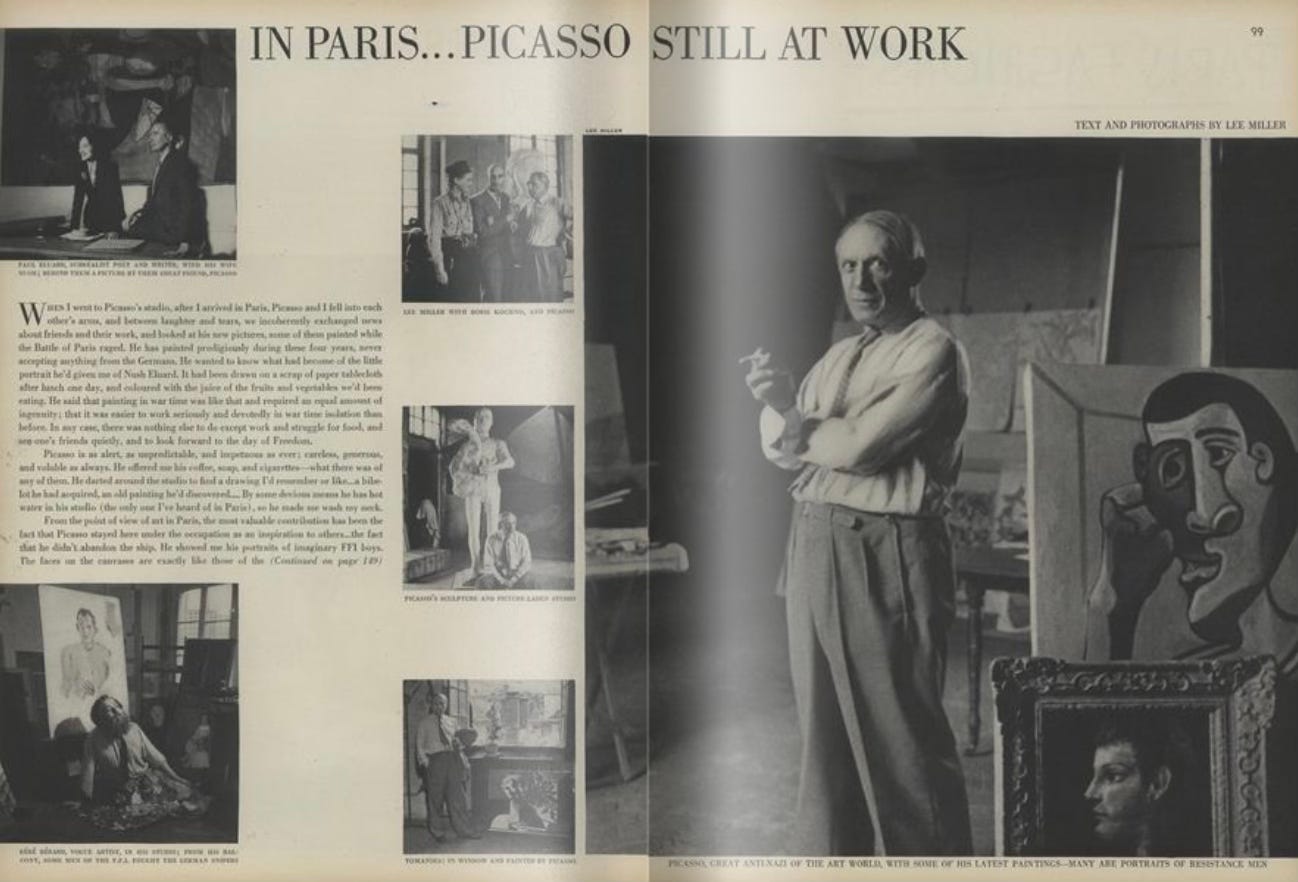

After the liberation of Paris, Lee Miller appeared at his studio door, and soon Picasso appeared in Vogue again, and in newspapers across America, next to the studio’s woodless stove, with loyal Kazbek at his side.

Picasso the Résistant, the image of physical and moral resilience, the hero that proved that the West’s values and culture had survived intact. A month later, at the 1944 Salon – renamed the "Salon de la Libération" – he was the featured artist, with 75 paintings on display, all wartime works except Guernica, which the Americans shipped over from MoMA for the exhibition – and then shipped back.

Five sculptures, too, including this one, which Brassaï shot six times.

Two days before, in Picasso’s Grands-Augustins studio, which by that point held the more than 400 works he had produced during the Occupation, was the meeting place of the Steering Committee of the National Front of the Arts. Picasso was elected its President. As such, at the meeting, he was called upon to ask the new Prefect of Police, his friend André-Louis Dubois (a Vichy civil servant who, along with Hitler’s favourite artist, Arno Becker, and Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, had protected Picasso during the war), to arrest and immediately sentence dozens of collaborating artists and critics, and request that “compromised” artists such as Derain, Maillol and Vlaminck, be prohibited from the official Salons.

The next day, he had dinner with General De Gaulle. According to his biographer, John Richardson, “Picasso became passionately in love with de Gaulle, and some Gaullists asked him to dinner. He went to the dinner, and when he came back, Dora Maar told me that he said, ‘C’est une bande de cons.’”

“They are dirty monsters, unfriendly, reactionary and without style,” he told Maar after the disappointing de Gaulle dinner, “no different than the collaborators they replaced.”

“We have not finished with the Nazis,” he told Dubois. “We have been infected with their smallpox. There are many infected, even without knowing it.”

And then, the following day, he signed with the Communist Party.

Sure, joining the PCF put Picasso automatically on the right side of history – the PCF ran the National Front of the Arts (which also selected works for the Salons) and organised the post-Occupation purge that saw as many as 100,000 people summarily executed. It instantly settled debates about his wartime activities – or inactivities – and gave him the stature of a resistance fighter, not someone who served tea to German officers and dined with collaborators “under the watchful gaze of a larger-than-life portrait of the Fuhrer, on deboned chicken wings and thighs speared between slices of veal on a golden sword.”

Should we judge him? Who will judge us?

“‘The shit in the shuttered château’10 is no one’s hero. But artists are seldom brave, nor need they be; and out of their honest cowardice, or blithe self-absorption, or simple revulsion from the world around them can come, in times of catastrophe, the fullest recognition of what catastrophe is – how it enters and structures everyday life. And as for artists who did not retreat or regress during the period in question— who went on believing in some version of modernity’s movement forward, toward rationality or transparency or full disenchantment— they were too often involved (the record is clear) in a contorted compromise with the tyrannies and duplicities… Better a private dreamworld, it seems to me, than a glib facsimile of the common good.” – T.J. Clark, Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica, 2023.

7.

“The modern artist must hate Picasso to make something new, just as Courbet hated Delacroix. – Marcel Duchamp, 1933.

The Autumn Salon opened on the day the newspapers reported Picasso’s adhesion to the PCF. It was the largest public exhibition of Picasso ever in France. The first to invite a foreigner. They also invited Surrealists – Miró, Magritte, Ernst, Tanguy, and Chaïm Soutine – and showed the works of 22 Jewish artists who had died in concentration camps.

The audience, however – not the audience that knew what a fucking violin was, but the one that found Kazbek’s sheep skulls offensive, the Tête de Mort unpleasant, the anguished, disfigured portraits and busts of Dora Maar indecipherable, and the handlebars and bicycle seat bull’s head –

– a bad joke, quickly turned into a mob:

“At the Salon d’Automne in 1944, six weeks after the liberation of Paris, the canvases of a painter whom the Germans had refused the right to exhibit for four years were taken down, smeared, and damaged by an organised group that operated with impunity. This group even boasted in the press about their actions, which were fully in line with the methods and theories of the Nazis.” – Les Lettres françaises, 21 October 1944.

“Viewers tore the sculptures to pieces and burned reproductions of them. After those incidents, the show was under the care of guards. Les Lettres françaises, the French Communist Party’s newspaper, considered the assaults on the works “acts of the enemy” and “vestiges of the intimidation tactics experienced during the Nazi occupation.” The newspaper took it upon itself to represent liberated France and to defend the artist – but not necessarily his work: the cover of Les Lettres showed an image of a work by André Fougeron, not one by Picasso.” – Andrea Giunta, “The Power of Interpretation (or How MoMA explained Guernica to its audience)”, 2017

8.

“Harisiades v. Shaughnessy, 342 U.S. 580 (1952), was a United States Supreme Court case which determined that the Alien Registration Act of 1940's authorisation of deportation of legal residents for membership in Communist parties, even past, did not violate the First Amendment, the Fifth Amendment, nor the constitution's Ex Post Facto Clause.”

“Under our law, the alien in several respects stands on an equal footing with citizens, [Footnote 9] but, in others, has never been conceded legal parity with the citizen. [Footnote 10] Most importantly, to protract this ambiguous status within the country is not his right, but is a matter of permission and tolerance. The Government's power to terminate its hospitality has been asserted and sustained by this Court since the question first arose. [Footnote 11]”

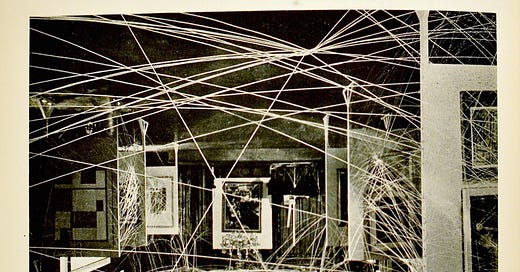

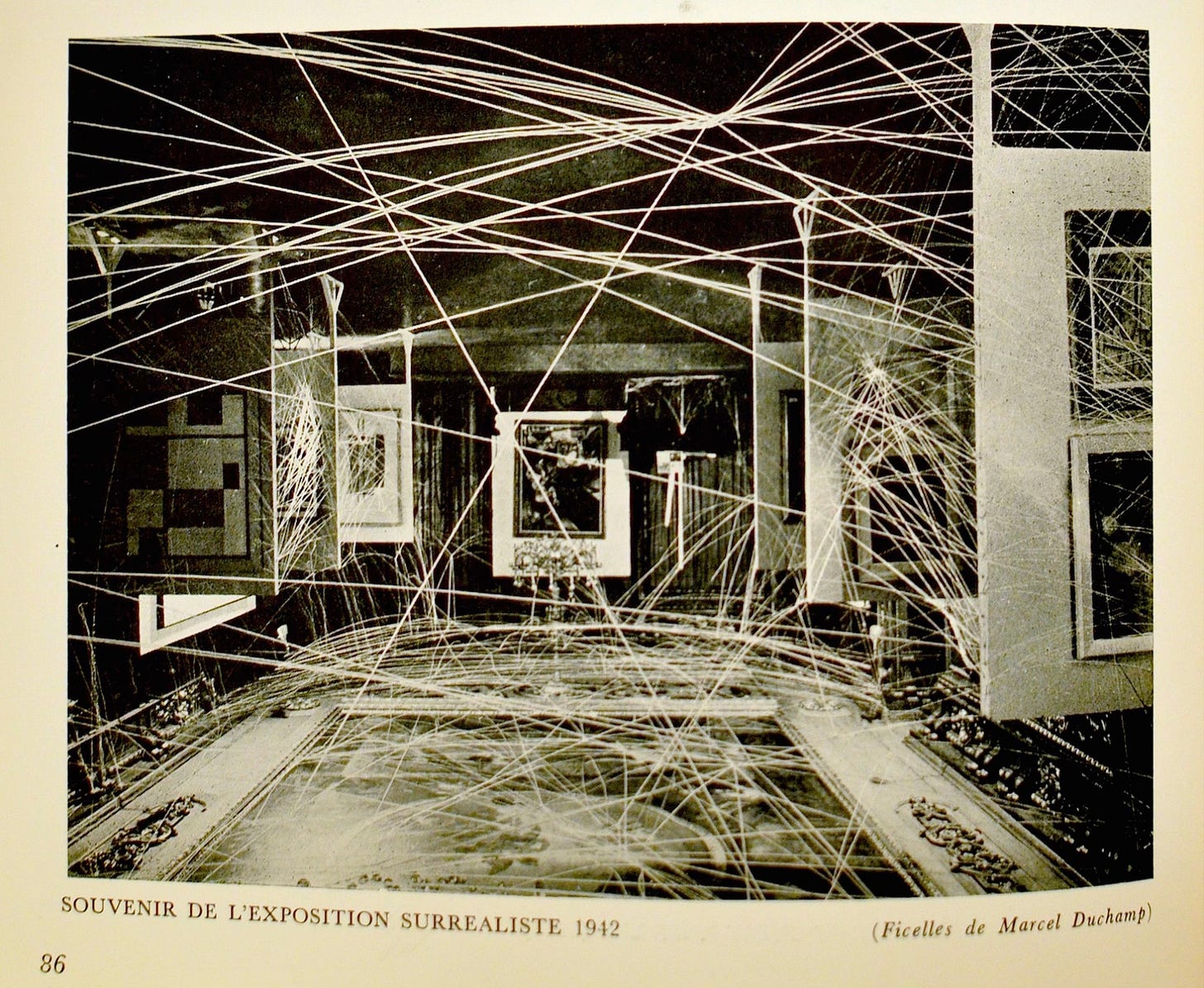

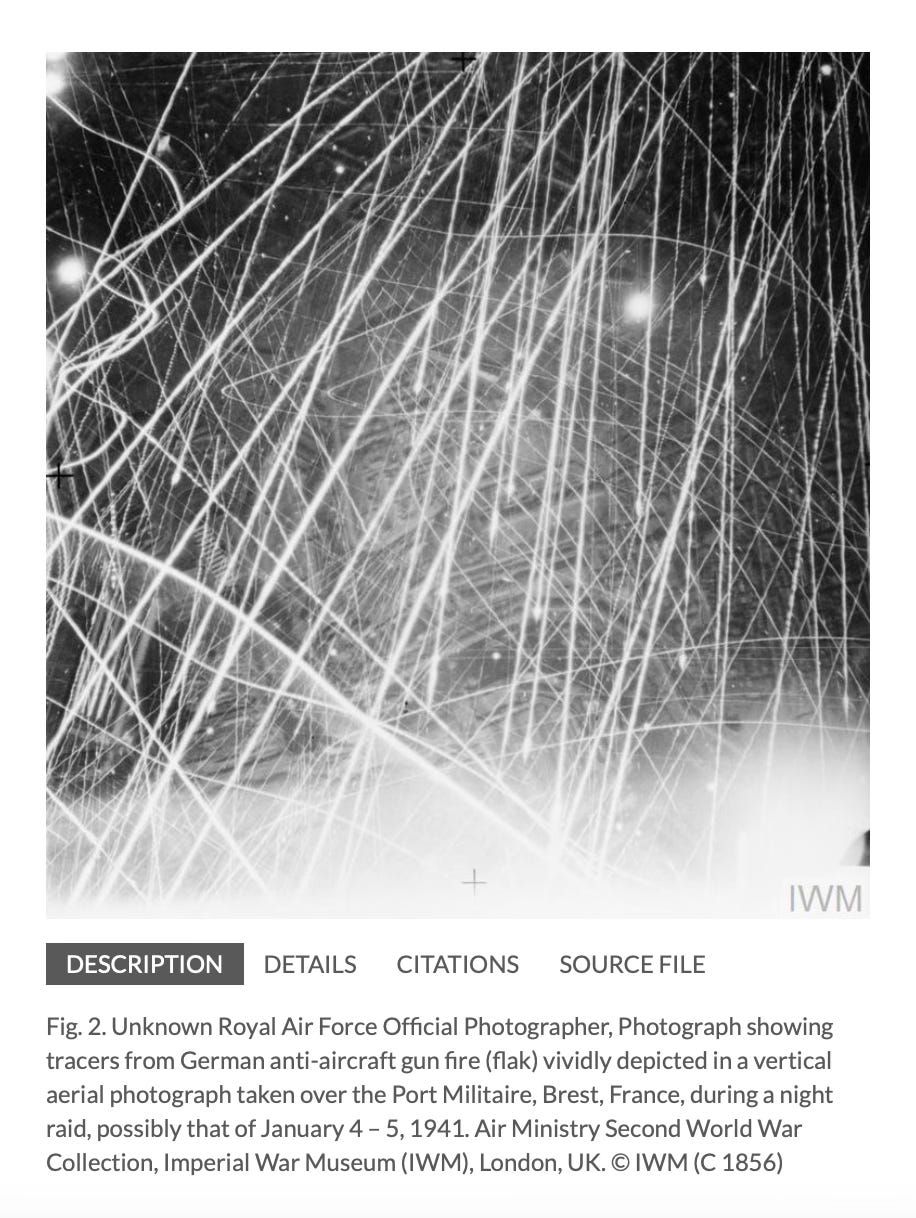

Nope, I don’t know Jasmine – no relation – this is getting a tad shaggy, and it’s Sunday, your Sunday and mine, and we all have things to do. But I do so want to “weave” in other elements. Mahmoud Khalil, for example. T.S. Eliot’s Guernica (“On the First of May The Tablet provided its explanation of the destruction of Guernica: the most likely culprits, according to The Tablet, were the Basque’s own allies, their shady [Spanish Republican] friends in Catalonia.” (T.S. Eliot, Criterion 16, July 1937). Duchamp’s ‘Guernica’ – His Twine – at the First Papers of Surrealism show in NYC in 1942: 11

“The exhibition’s title referred to the first step in the process of naturalisation by which an alien becomes a United States citizen. After residing in the USA for two years, an alien could file a ‘declaration of intent’ to become a citizen, a process referred to as ‘first papers’ on the road to citizenship. After three additional years of residence, the person could petition for naturalisation. A certificate of citizenship would be issued after the petition was granted. For the surrealist artists, displaced by a war that showed no sign of ending soon, questions of home and citizenship remained pressing.” – James Housefield, “Marcel Duchamp’s Guernica?: “His Twine,” the First Papers of Surrealism (1942), and Aerial Warfare in Europe”, 2019.

And how Jack Kennedy hated music despite having a centre for performing arts named after him. It hurt his back. It hurt his ears. He never knew when the composition was over. He was always clapping at the wrong moment. The music was all Jackie. “Constant music,” she had insisted when they took possession of the White House. “No dull moments.”

And how, in 1932, Duchamp, already more focussed on chess than anything else, produced The Box of 1932, which contained miniaturised reproductions of his drawings and notes, and Agfa, by then part of the infamous IG Farben cartel, introduced a new series of colour film products called Agfacolor, and George Eastman, the founder of Kodak, suffering from a degenerative disability resulting from the hardening of the cells in his lower spinal cord, shot himself in the head.

But this post is already 20 feet long, and who knows how much more of it goes down into the auger-dug post hole – or, to return to that calm, clear North Atlantic night of 15 April 1912, how much more of its icy bulk is hidden in the icy depths. So before I rip a series of elongated tears in the starboard side of my hull and leak out a bunch more subscribers, I’ll stop – with all these barely asked questions left unanswered – and turn towards port, following the navigational advice of the many, many, many writing experts on this platform, who all concur that to be a success here, a metric measured not in coffee spoons but coffee cups – one a month per paying subscriber – a certain degree of “volume control” is required. Here, out of nowhere, my brain processes are cycling through my student days, back when I was living on the edge of the grid and freebasing Foucault:

So, if you haven’t already left, how about I leave you with this: you don’t have to be a miserable little shit to be politically engaged, no matter how fucked up things are. Don’t fall for power. Be careful what you wish for, and who you listen to, avoid the moving mouth, the loud hand, and the unreflective eye. It was the Germans, H.G. Wells tells us, “those disastrous people, who first discovered that slag heaps and by-products might also count as learning, but I doubt if we can blame any one race or nation in particular for setting dumps and dustbins above the treasure cabinets of scholarship.”12 So keep digging, but be suspicious of what you unearth. History stops and goes, but fascists last forever. Final note: Though he badmouthed Picasso, Hitler respected Speer’s and Becker’s opinions,and he had a deep and abiding love of painting and paintings. His favourite was the forest landscape Wölfe im Wald vor einer Höhle (Wolfsschlucht) by Caspar David Friedrich. Painted in 1798, it depicts two starving wolves gnawing on a deer skeleton near the mouth of a forest cave. A startled hart and doe stand behind them, dead still, frozen with fear, having just emerged from the cave’s darkness into the stark, grim light of their imminent and savage death. But the wolves bent to their pointless task — the skeleton bones have no meat on them, they are old, bare, bleached white — have not yet seen the two frightened deer. Light shimmers on the boughs of the trees. It is summer or perhaps early fall; the leaves look like they are starting to colour. The deer are too afraid to move, to breathe. The wolves have not caught their scent. The sky above the trees is growing dark. A storm is approaching. In the foreground, visible to the viewer but hidden from the animals by the hollowed-out trunk of a giant dead oak, a third wolf watches. He looks healthier than the other two. Plumper, sleeker. Smarter. He pricks up his ears, licks his chops, and rears up on his hind legs.

Much of the allegorical meaning is obscure. The hollowed-out tree, presumably, is a symbol of transience, the skeleton, of death. The starving wolves? The frightened deer? The smarter, plumper third wolf licking his chops, standing on his hind legs like a man?

“There is no melancholy here, nothing lofty, nothing sublime,” Hitler told assembled guests, who hung on his every word. Dinner was over; they were assembled in the front parlour of the Fuehrer’s private apartment at the Chancellery. The walls were baroque blue, white and gold. The Fuehrer was wearing a civilian suit and Eva Braun’s favourite necktie, from Milan. The oak and cherry floors were inlaid with streaked white and grey Carrara marble. The windows were blacked out. A tapestry — Wotan Creating the World — covered a wall. A Dutch 17th-century celestial globe, similar to the one that Leeuwenhoek, the astronomer, spins in the Vermeer portrait, occupied a corner of the room. In less than two minutes, it will be destroyed by a bomb dropped from a P-51 Mustang.

“Only coldness, death, cruelty and cunning. This is our nature and the means of our salvation.”

Schnapps had been served. The Fuehrer poured coffee into delicate cups. “But are we to be saved?” The light caught his gold tooth, which never showed in the photographs. “Are we worth saving?” The visitors sipped their schnapps in silence, perhaps afraid to speak.

“We have forgotten this truth,” he said, pointing at the deer and the bigger wolf, “that Friedrich captures so perfectly.”

An air-raid siren went off, startling the guests. Then another, a bright flash, a shriek. Two explosions, just outside. The chandelier tinkled and swayed. Hitler filled another cup.

“The wolf’s return,” he whispered. “We must relearn this. Rebuild this. Not just to be saved. To triumph.”

The room went quiet. No one moved. Elsewhere, in the hall, footsteps, shouts, running. All the sirens, every siren in the city. The night filled with flak fire. The bombing stream – Lancasters, Halifaxes, Mustangs, Mosquitos – turned the sky black.

The wall split open wide. The tapestry lit on fire.

Ta.

Especially if they were tuned to Voice of America, which began on February 1, 1942, and survived 83 years before Trump killed it yesterday (15 March 2025).

A ballpark figure: about nine football fields, so just under half an NFL season.

Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, 1851-52.

“Degenerate” Art: The Trial of Modern Art under Nazism,” Musée Picasso, Paris, until May 25.

“I have long since come to an agreement with destiny: that is, I have, myself, become destiny— destiny in action. . . . My trees [or guitars] aren’t made up of structures I have chosen but structures that the chance of my own dynamism imposes upon me. . . . I have no pre-established aesthetic basis on which to make a choice. I have no predetermined tree, either. My tree is one that doesn’t exist, and I use my own psycho-physiological dynamism in my movement toward its branches. It’s not really an aesthetic attitude at all.” – Picasso, cited in T.J. Clark, Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica, 2023. “The French text has an extra sentence: ‘In any case, there is no visual sensation, since I never work from nature.’ (Il n’y a pas de sensation visuelle, puisque je ne travaille jamais d’après nature.) The whole passage is a struggle with Cézanne.”

The term juste milieu was used during the July Monarchy (1830–1848) to describe centrist, “middle-of-the-road” political philosophies. It later extended to art to describe a “middle way” between conservative academic painting and the lighter, looser work of Impressionism. Overly technical and polished work was to be avoided, but so were the radical techniques of the “avant-garde”. The Fauvistes – the painters called wild beasts – fauves – for their odd colours and shapes – were the best examples in Picasso and Duchamp’s time. Their work was championed during the Vichy regime and the German occupation, especially the paintings Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, and, to a lesser degree, Henri Matisse.

“Pompier” art, aka Academic or Salon art, was a derogatory term for the dominant style of late 19th-century painting. Large-scale, historical or mythological, grandiose, meticulously technical – the kind of painting that appealed to Nazis. So-called because of the “pompiers” – the shiny firefighters’ helmets that look like the ones Ancient Greeks wear in the paintings.

When I throw back my head and howl People (women mostly) say But you've always done what you want, You always get your own way - A perfectly vile and foul Inversion of all that's been. What the old ratbags mean Is I've never done what I don't. So the shit in the shuttered chateau Who does his five hundred words Then parts out the rest of the day Between bathing and booze and birds Is far off as ever, but so Is that spectacled schoolteaching sod (Six kids, and the wife in pod, And her parents coming to stay) . . . Life is an immobile, locked, Three-handed struggle between Your wants, the world's for you, and (worse) The unbeatable slow machine That brings what you'll get. Blocked, They strain round a hollow stasis Of havings-to, fear, faces. Days sift down it constantly. Years. – Philip Larkin, "The Life with the Hole in it", 1974

Quoted in the Translator's Introduction (Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wurtz) of Friedrich A. Kittler's Gramophone. Film. Typewriter., 1999.

One of my favourite reads of

Yours - xo

bravo